Light streams through a stained-glass window in the Norbertine canons' Church of Our Lady of the Assumption in Silverado, California, in this undated photo. (OSV News/Courtesy of St. Michael's Abbey)

In our busy lives as women religious we are often known by our ministries, roles or titles. It is sometimes difficult to explain who we are beyond our daily tasks and responsibilities.

In this panel, we gathered to dig deep into the question: "When we stop doing, we ask ourselves, who are we? When you are not working in your ministry, who are you?"

______

Begoña Costillo is a member of the Order of St. Augustine and lives in the Monastery of the Incarnation in Lima, Peru. She entered religious life in 2012; since then, she has lived in Spain, Italy and Peru.

I remember the many personal conflicts we all suffered during the terrible time of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was not only the fear of getting sick, of dying, of losing our loved ones, but also the boredom and anguish of not being able to do the things we normally did: work, pursue projects, have fun, be productive and so on.

However, for a significant part of humanity, those days are over and, almost, forgotten. We returned to our jobs, our endless tasks, entertainment, fun and our exciting projects. With all the possibilities once again within our reach, we recover our own way of understanding existence, to each his own. It is possible to live with the sole pretension of fulfilling oneself, of gaining well-being or power or fame; or to live in pursuit of the comfort of a life with few surprises and, at the same time, with some emotions that embellish it.

A sister prays in the cloister of the Monastery of the Incarnation in Lima, Peru. (Courtesy of Begoña Costillo)

We religious also sometimes have similar pretensions, although veiled under serious spiritual reasons. We may think that life consists of unfolding our being in what we do, because we "are" someone by the measure in which we do useful things for the community, for the church, for the poor, etc. And so, when our weekly program unexpectedly presents a vacuum that leaves us vacant, or when unwillingly a position is taken away from us or we are changed from a mission in which we felt recognized, a restlessness reappears in the depths of our soul, similar to that anguish we experienced when confinement did not allow us to work, to carry out projects, to save the world.

If I have to ask myself who I am outside of my ministry, then I have not understood what "being" means, because action, as true philosophy has been saying for centuries, follows being. That is to say, what I do is not a way of constructing what I am, but on the contrary: Only from a profound identity is it possible for fruitful works to emerge that express the essential being of the person. And only if this inner being has been given birth by the new life of the Spirit that confers on us the identity of children of God will our works be seeds of the Kingdom and not anchors on which to affirm our personality.

It does not matter if I am doing the highest or the humblest work, or if I am resting, or watching a good movie, or ill and bedridden, because I am always a beloved child.

Then, it does not matter if I am doing the highest or the humblest work, or if I am resting, or watching a good movie, or ill and bedridden, because I am always a beloved child and with my simple existence I am a manifestation of the love of God the Father and, in this way, I shine my light on the world, I am a seed of the Kingdom. And my life therefore, has profound meaning, as our friend Miguel García Baró, a great Spanish philosopher, told us one day: "An essential advance is made when we understand that we did not come into the world to fulfill a mission other than that of having been born: that of being the miracle of an original, secret life, much more real and profound than death. This is a miracle that speaks to all of marvelous good, unspeakably greater than any pretended mission without whose fulfillment everything remains truncated, failed and meaningless."

Kathleen Feeley, a School Sister of Notre Dame, served as president of the College of Notre Dame of Maryland (now Notre Dame of Maryland University) 1971-92. She has taught college, high school and elementary students. After her college presidency, she taught literature in India, Australia, China, Japan and Ghana. Feeley has a master's degree in English from Villanova University and a doctorate from Rutgers University. She now teaches at Notre Dame of Maryland's Renaissance Institute, which serves lifelong learners over age 50.

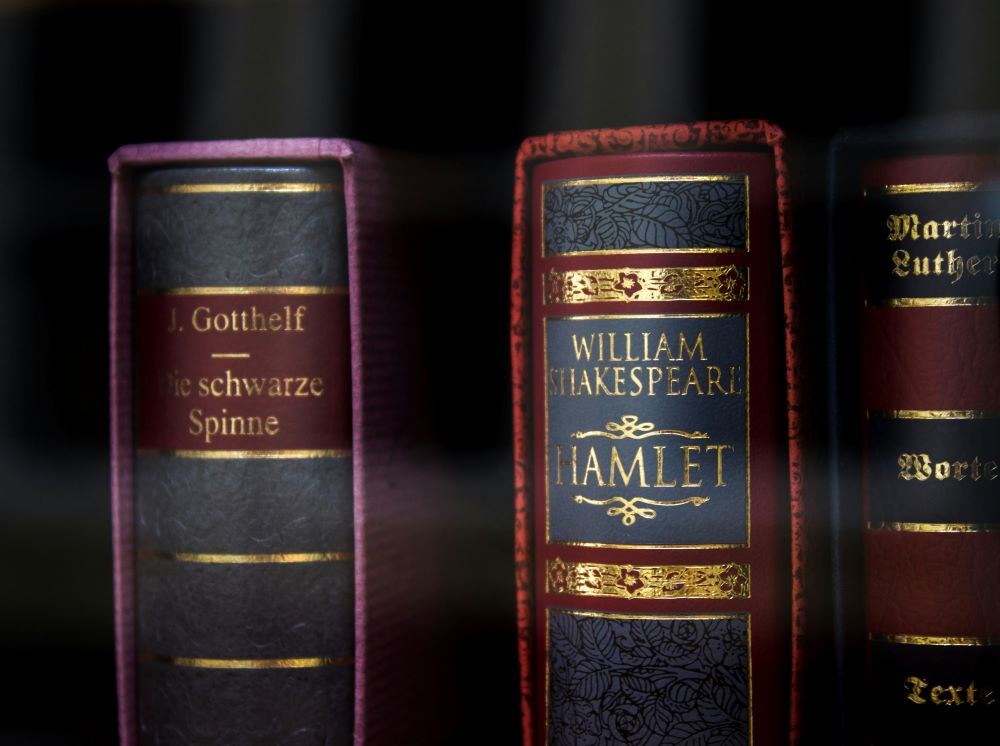

"This above all: to thine own self be true, and it must follow as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to anyone." Shakespeare's words from "Hamlet" run deeply true as we contemplate the ongoing stages of our lives.

(Unsplash/Max Muselmann)

Socrates was perhaps the most renowned philosopher who exhorted, "Know thyself." That knowledge is not easily attained. It takes years of living and soul-searching to learn one's motivations, name one's fears and graces and analyze one's reactions.

To know oneself is first; to be true to oneself follows.

In our lifetimes, we experience the stages of youth, maturity, and old age. For many of us, old age is the hardest because we can no longer do what has been our life's work: raising a family, serving others in a life-giving career, or ministering in a service organization in which our lives are other-directed. Each of these paths bring financial resources and satisfaction, but each can also lead to the hidden slide into the belief that we are what we do.

For example, I have been a teacher, on different levels, in many settings, in several countries, for 75 years. This present semester is the first time since age 20 that I have not been standing in front of a classroom interacting with students of all ages. I miss the moments of enlightenment (theirs and mine), of seeing eyes light up, of hearing a response or a comment from a participant who speaks a newly acquired understanding. All this makes my heart happy.

These experiences are happiness in my calling. They do not define who I am.

To know oneself is first; to be true to oneself follows.

I have found that, as people age past the time of "doing," they sometimes get depressed because they can no longer contribute their gifts of mind and spirit to others. It seems that they lose their identity when they are not working. However, if along the path of life, they have acquired the understanding of their unique personhood, they would never unite into one entity "being" (God's singular creation) and "doing” (their life's work).

These elders know who they are; they are content to be who they are, who they have been since the day of their birth. They know themselves deeply, and they are true to themselves: What the mind believes and the heart affirms is expressed in their words and actions. They have developed a basic integrity, which gives their lives deep meaning, which nourishes joy.

Lucy Zientek is a Sister of Divine Providence, Melbourne, Kentucky, and currently serves on the leadership team of her congregation's U.S. province. She has 14 years' experience as a research and development scientist prior to entering religious life. She has served on parish pastoral teams in the areas of adult faith formation, Christian initiation and pastoral ministry. She also presents retreats and days of reflection. Supported by an educational background and career and ministry experience in science, theology and spirituality, her special area of interest is the relationship between science and faith.

St. Paul wrote that once we have come to the conviction that Jesus died for all, "the love of Christ impels us" to love others as Christ has loved us. The need to proclaim Christ's love to others by word and deed is rooted deep in the heart of every religious. It is like an ever-burning fire raging every bit as much in one’s "being" as in one's "doing," and forges who we are as persons. Our congregation's constitutions call our attention to this when they say: "Whatever our forms of ministry, we speak the message of God first of all by the way we live. It is the quality of our presence that effectively allows Christ's love to be felt by others and helps us to know Him in them." We become "signs of hope" and "living expressions of the benevolent tenderness of God primarily through the way we are present to others.

Our founder, Blessed Jean Martin Moye, was an 18th-century French priest. He sent the first sisters to the most abandoned places of the French countryside to practice the spiritual and corporal works of mercy, specifying that their main duty was to teach those uninformed or ill-informed about the mysteries of faith. Three centuries later, how do we approach being who the Spirit has called us to be? We live in a polarized world on the brink of climate collapse, and where Jesus’ resurrection has become even imaginatively implausible for many contemporary believers (see Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Sandra Schneiders in Jesus Risen In Our Midst).

Last year our general chapter did its best to discern the Spirit's promptings about how we can respond over the next five years to that ever-raging, holy fire in our hearts, and articulated this for us in just a few words. The more I ponder them, the more I see how this is wisdom for any person seeking to respond to the call of the Spirit today:

Listen to the cry of those whose hope is threatened.

Listen to the cry of our suffering Earth.

Act, with others, with enthusiasm and creativity.

Listening is integral to our presence to each other. We need to listen, the Spirit tells us, especially to those despairing of hope. We need to listen to the cry of the planet, the only place we all share and which we can no longer neglect. And listening, we need to act and be creative together, the Spirit tells us. The fire in our hearts will fuel both our "being" and our "doing," for it is the Love Who is the Risen Christ longing to break through and embrace us all.

Advertisement

Hna. Ruth Karina Ubilus, Hermanas Educadoras de Notre Dame. (Foto: GSR)

Ruth Karina Ubillus, a member of the Congregation of the School Sisters of Notre Dame, was born in Peru. With 12 years of teaching experience in public schools, she joined the congregation in 2006 after her novitiate in Brazil, where her missionary calling began. During her journey, she discovered the significance of "inner child" work in Guatemala, emphasizing its crucial role in personal growth and development. She holds a diploma in spiritual direction. She previously lived in Brazil for four years and since 2020 has lived in South Sudan, where she is driven to help individuals in their journey of personal growth and development.

(Unsplash/Simon Hurry)

I was one of those deeply rooted in our work, especially within our ministries, which often consume much of our time and energy. I have found that it is easy to confuse our identity with the roles we play. However, when we step away from those roles or responsibilities we are faced with the fundamental question of self-discovery: Who are we beyond our work or the roles we play? I saw myself as very effective and committed to my work, but often disconnected from my own being. I have seen in my own experience the inner turmoil arising from too much work, from the burden of responding to people's expectations, from resorting to masks while not being true to my own convictions or values. All this affected my relationships with myself and with others.

When we take a break and step away from our ministry, we discover our own inherent humanity, —that which is not defined by professional titles but by the richness of our experiences, relationships and our inner being.

The lack of joy and dissatisfaction stemming from not knowing my authentic self has been profound. However, thanks to moments of silence, prayer and even difficulties or stress, I have been able to ask myself vital questions: Why do I do what I do? Why do I feel agitation? Am I truly happy in what I do? Do I feel fulfilled? To whom or for what do I dedicate my work? Is it worth it? What rewards do I expect, etc.?

I am unique, I am loved, I am light, I am joy, I am hope, I am goodness. I am someone who shares the divine essence of God himself.

When I'm not engaged in ministry, I am, first and foremost, a being with a concrete story. This narrative of my life has formed me, providing me with an identity, though it may not always be the authentic one. It has instilled in me values, personality traits, dreams, fears and insecurities. Deep down I am a being in search of meaning and purpose in existence. In this pursuit, I have been found by the One who created me, the God who accompanies my life journey and who seeks a constant relationship with me.

Through this relationship, my being finds itself, embracing that real and only identity bestowed upon me. Accepting this transcendent essence of my life provides me a deeper sense of authenticity, resilience, fulfillment and hope. My identity transcends the confines of any specific role or occupation. When I recognize myself living out my true essence, the joy and satisfaction of being who I am is priceless: I am unique, I am loved, I am light, I am joy, I am hope, I am goodness. I am someone who shares the divine essence of God himself.

A Benedictine Sister of Chicago since 1988, Susan Quaintance currently serves as her community's subprioress; she also works part time as director of Heart to Heart, a ministry for seniors at a nearby parish. Classrooms are where she most feels most at home, having spent decades teaching in a Benedictine single-gender high school for young women and then directing an educational outreach program for older adults in downtown Chicago. She sits on the board of the United States Secretariate of the Alliance for International Monasticism and on the council of the Monastic Congregation of St. Scholastica.

In the summer of 2004, another sister from my community and I were fortunate enough to be invited by the Women's Commission of AIM USA (Alliance for International Monasticism U.S. Secretariate) to present a series of workshops at monasteries in Uganda and Kenya. It was my first (and, so far, only) visit to Africa and, certainly, a transformative experience of being immersed in cultures very different from my own.

One of the most jolting lessons I learned came from repeated introductions as we traveled from place to place. I would meet a new sister or monk, and she or he would ask me about my life in the United States. I noticed that once I had said where I was from (Chicago), and what my job was (teacher), I would be met with quizzical faces. The other person would keep asking me questions, breezing over that I thought revealed the most about me: what I did for a living. The facial expressions on my conversation partners during these encounters taught me something important. As an American, I unconsciously thought that my job told people who I was. My Ugandan and Kenyan hosts didn't really care about that; they wanted to know about Susan Quaintance. Intellectually and spiritually, I understood that my basic humanity wasn't affected by the job I went to every morning. But as a woman more of my culture than I would have ever dreamed, my emotions told me that I absolutely tied my worth to my ministerial "doing."

A plaque on a building in downtown Chicago commemorates the establishment of the Benedictine Sisters of Chicago in 1861. This marker pays tribute to the legacy of the Benedictine Sisters and their significant contribution to the community. (Susan Quaintance)

So, in the 20 years — and four jobs — since, one might think that I would have come up with a cogent and thorough answer to the question, "When I am not working in my ministry, who am I?" Well, sort of. But my time in Africa, and a year of being unemployed, helped me understand that it's pretty hard to turn off cultural assumptions and values that are the water I've been swimming in for a lifetime. One thing that has helped me answer is being asked to articulate "who I am" in various ways during discernment processes for positions within my community or monastic congregation. Those experiences, and ensuing conversations, have assisted me in figuring out who I am beyond what I do.

The through line in my responses has been the Benedictine charism. What grounds me is my understanding of myself as a monastic woman. I experience and make sense of the world through a lens shaped by stability, conversion and obedience (our vows); by humility, silence and hospitality (our key values); by liturgy (the opus dei or "work of God").

For most of the past decade I worked in downtown Chicago. My trip to the office usually involved crossing the street at the corner where my community was founded in 1861; a plaque on a building that used to be a Starbucks commemorates that. I would touch that plaque on my way to work to remind myself who I am, who I come from. It helped.