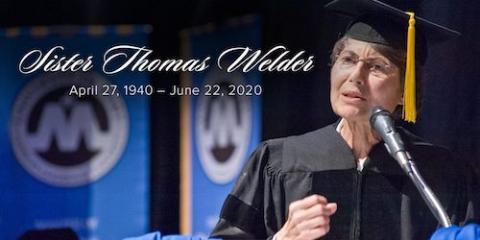

Benedictine Sr. Thomas Welder in the North Dakota* prairie (Courtesy of University of Mary/Jerry Anderson)

She wasn't the CEO of a large corporation. She never held elected office. She spent 59 years living in a monastery on a wind-swept ridge overlooking the Missouri River on North Dakota's prairie. She was neither bombastic nor physically imposing but slender and self-effacing. Yet Benedictine Sr. Thomas Welder remains a monumental presence, even after her death on June 22, 2020, at the age of 80.

I got to know Sister Thomas in 2019 when she invited me to speak at the University of Mary in Bismarck, North Dakota, on "Stirring the Ashes: Igniting a Sense of Hope in Our Work." Her own life leaves an indelible handprint on the hearts of those of us lucky enough to have known her of what it means to be a servant, a leader, a person of faith and exemplary human being.

As our country moves toward the final results for the presidential and congressional elections, this Benedictine sister's example speaks volumes about what true leadership means.

In 1978, Sister Thomas became president of Mary College, then a small, liberal arts college on the Dakota prairie. She had a sweeping vision. It was to transform Mary College into the University of Mary, one of the country's premier institutions for educating future leaders.

Named to the position when she was 38, she became the longest serving female president of a university to date in the U.S. (31 years). Under her leadership, the university tripled in size from 925 to 3,000 students, added a doctorate program, and established satellite learning programs across North Dakota and the country.

If you search Sister Thomas' name on Google, you can treat yourself to watching one of the videos in which she might be found speaking passionately about her signature subject — servant leadership — in her distinctive, plainspoken, self-deprecating, and humorous style. She insisted that the University of Mary would not become a place that turned out your typical MBA, get-ahead, get-rich, seek-the-limelight-type of leaders. It would be a training ground for servant leaders.

An early influence on her thinking was Robert K. Greenleaf's seminal 1970 essay, "The Servant as Leader." Greenleaf was a former AT&T (American Telephone and Telegraph, precursor to today's media giant) executive who concluded after his long tenure at the top that the authoritarian, command-and-control, top-down leadership model was no longer serving the needs of our country, its corporations or its workers.

Sister Thomas advocated for a different, pyramid-shaped model. On the sides of a triangle, she paired "Service" with "Vision" and placed both those values firmly on a base of "Credibility."

"People won't listen to the message if they can't trust the messenger," she was fond of saying. Effective leaders, she observed, don't seek to influence by "force, coercion, control, or authority," but by "respecting the needs of those in their service." They aren't big talkers. They are devoted listeners

Benedictine Sr. Thomas Welder (Courtesy of University of Mary/Jerry Anderson)

Here, Sister Thomas didn't need to turn for guidance to any of the latest books by management experts. As a Benedictine sister, she was intimately familiar with one of history's most famous guides for living and leading with compassion: the monastic Rule of St. Benedict.

A sixth-century text written expressly for monks might seem an odd guide to address our rapidly changing 21st-century social, political and business practices. But from its first sentence, "Listen … with the ear of your heart," the Rule echoes guidance coming from many of today's top organizational and management voices.

In his chapter on electing a monastery's abbot or prioress, Benedict explores the character traits essential to good leadership. They prove remarkably similar to those historian Doris Kearns Goodwin cites in her 2018 book, Leadership in Turbulent Times, on the presidencies of Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt.

Those character traits? Humility — that is, a willingness to learn from mistakes. Empathy. Resilience. Self-reflection.

St. Benedict says in his Rule that those who seek to lead must do so not by words, even soaring ones, but by "living example." In one of his most memorable passages, he compares a leader to a physician whose objective is "the care of souls."

Advertisement

Sister Thomas would often end her talks with a series of questions she called the "tests of true leadership." Do those I serve grow as people because of my leadership? Do they become healthier, wiser and more likely themselves to want to serve? What effect does my leadership have on the least privileged, most marginalized in society? And, does my leadership serve to build community?

These seem apt questions to ask ourselves as we evaluate political candidates, as well as our business leaders.

Sister Thomas' own path to leadership was a personal profile in courage. At the height of her career, she was struck with kidney disease, endured dialysis, and eventually received two separate transplants.

"She knew she was on borrowed time this side of the clouds," her longtime friend, Sr. Anne Shepard, observed. "No one lived one day at a time more than she did. No one loved life and recognized the value of each day more than she did. What a model she was of what it means to be Christ-like."

Despite her pressing duties in recent years as president emerita and ambassador-at-large for the university, she still managed to sing with and conduct her monastery's choir and play the organ at daily community prayers. She had a master's degree in music from Northwestern University.

"Jesus Washing the Feet of his Disciples" by Albert Edelfelt, 1898 (Wikimedia Commons/Nationalmuseum of Sweden/Bodil Karlsson)

Another of her favorite expressions was, "It's the people who matter."

Anyone who spent time with her quickly realized she had an uncanny way of aiming the spotlight away from herself and making those she was with feel as though they were the most important people in her world at that moment.

Sr. Nicole Kunze, prioress of Annunciation Monastery, said Sister Thomas spent her final hours before succumbing to kidney cancer meeting individually with each sister in her community.

"It's the people who matter."

She often included in her presentations images of Jesus washing the feet of his disciples. She would point out that before any management gurus seized on the idea, Jesus was the original "servant leader."

Sister Thomas was the epitome of servant leadership. May we be inspired to follow her example. It's the people that matter.

*An earlier version of this caption gave the wrong state.

[Judith Valente is the author of How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community and the senior correspondent at GLT Radio, an NPR affiliate in Illinois. She is a Benedictine oblate of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery in Atchison, Kansas, and has served on the volunteer board of the American Benedictine Academy since 2014.]