London's British Library's exhibition, "Medieval Women: In Their Own Words," introduces the women of medieval Europe through their own words, visions and experiences (Courtesy of British Library)

Shakespeare may have immortalized the phrase "get thee to a nunnery," but a new exhibition at London's British Library challenges stereotypical understandings of religious life in the medieval era.

In "Medieval Women: In Their Own Words" — on display until March 2025 — a different story is presented of the lives of medieval women, including the contributions of religious sisters.

"A lot of our decisions with the exhibition were based on wanting to counter some of the misconceptions people have about the Middle Ages," said curator Eleanor Jackson. "One of the ideas people have about nuns, specifically, is that it was maybe quite a limited life."

Jackson told Global Sisters Report that too often there is the false narrative of nunneries as "a bit of a dumping ground for women that couldn't get married or whatever."

"We really wanted to show that it wasn't that case at all and it was a way to live a very culturally rich life and that nuns had all of these opportunities for learning and to do creative things," she said.

Advertisement

On display in the major exhibition, which opened in October, viewers will discover a rare medieval painting from a nunnery, the first definitive English text authored by a woman and other artifacts that upend many traditional narratives about women of this time.

The exhibition — through prayer books, prints and textiles — chronicles the lives of nuns that were independent, creative and human.

According to Jackson, who serves as the British Library's curator of Illuminated Manuscripts in the Western Heritage Collections, many scholars are often dismissive of the books made by nuns and for nuns.

"They're relatively unappreciated," she told GSR. "Certainly, they haven't been displayed as a group before."

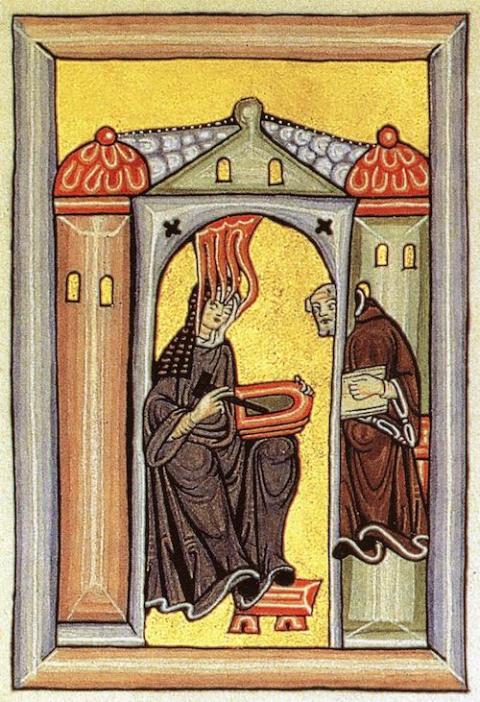

Hildegard von Bingen. (Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

But now, said Jackson, the "Medieval Women" exhibition provides an "opportunity to put them on display and show how glorious they are."

Inside the gallery, viewers are introduced to individuals such as the 12th century German Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen and the Alsatian nun Herrad of Landsberg, whose lives and works attest to the prolific nature of the art and manuscripts religious women were producing at the time.

Jackson noted that medieval art, as well as art that was produced in a monastic context, is very different from art that is often found in modern art galleries.

"There was no sense of art for art's sake. This is all religious, spiritual art that they were producing for purposes of devotion," she said.

But although there may not have been the same freedom of expression that is associated with contemporary art, Jackson said "there was a lot of freedom for them within the requirements of religious art where they were able to find ways to express themselves and their own unique spirituality."

One example she cited is the 15th century Poor Clare nun, Sibilla von Bondorf, who produced depictions of Christ the Good Shepherd — an image that dates back to ancient times, but with a new twist: instead of Christ carrying a sheep, he is carrying a little nun.

"As far as I'm aware, that's an innovation unique to Sibilla," said Jackson. "She was coming up with new ways of expressing her spirituality."

"There was no sense of art for art's sake. This is all religious, spiritual art that they were producing for purposes of devotion."

— Eleanor Jackson

As the artifacts and keepsakes on display here demonstrate, the lives of nuns included much prayer, reading and devotion — alongside their production of manuscripts, textiles and the often weighty work of managing their convents and estates.

One of the aims of this exhibition, said Jackson, is to "counter this view that it would be an unpleasant life living in a convent."

"People think it's unrelatable," she continued, "but when you read about the individuals you realize they're much more recognizable than you might think."

And lest there be any doubt: also recorded in the exhibition is the autonomous streak of nuns who had pets — ranging from dogs to monkeys — even when bishops or priests told them it was inappropriate.

That decision to keep pets, said Jackson, helps "humanize them."

The National Catholic Reporter's Rome Bureau is made possible in part by the generosity of Joan and Bob McGrath.