Volunteers for Catholic Relief Services in Zambia preparing a demonstration meal, stressing the need to use local crops and ingredients in meals. (Catholic Relief Services/Dooshima Tsee)

For years as a journalist reporting on humanitarian crises, I've witnessed the horrible disconnects and huge inequities in the world's food system — which have only worsened during the global pandemic.

In July, the World Health Organization noted that up to 811 million people were undernourished in 2020 — "a dramatic worsening" from the year before, and much of it "likely related to the fallout of COVID-19," WHO said.

That's something to ponder as the world commemorates World Food Day on Oct. 16 — set aside by the United Nations to commemorate the founding of the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization in 1945 but also to take stock of the state of hunger and other food-related issues in the world.

The situation is dire, given climate change and other grave challenges facing humanity and the planet as a whole. But front and center, of course, is the pandemic.

"Unfortunately, the pandemic continues to expose weaknesses in our food systems, which threaten the lives and livelihoods of people around the world," the heads of five United Nations agencies, including the FAO, wrote in the annual State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World.

Emily Wei, director of policy for Baltimore-based Catholic Relief Services, agreed with that assessment.

Advertisement

"We're at a real inflection point," Wei told me, adding that the pandemic has "laid bare" the serious shortcomings of the global food system — including its overdependence on fossil fuels and the fact that so many people remain hungry or undernourished.

Given that, there is a sense of real urgency as the United Nations marks World Food Day 2021, with calls for meaningful change — including personal change.

"The food you choose and the way you consume it affect our health and that of our planet," the United Nations says in introducing this year's World Day theme. "It has an impact on the way agri-food systems work. So you need to be part of the change."

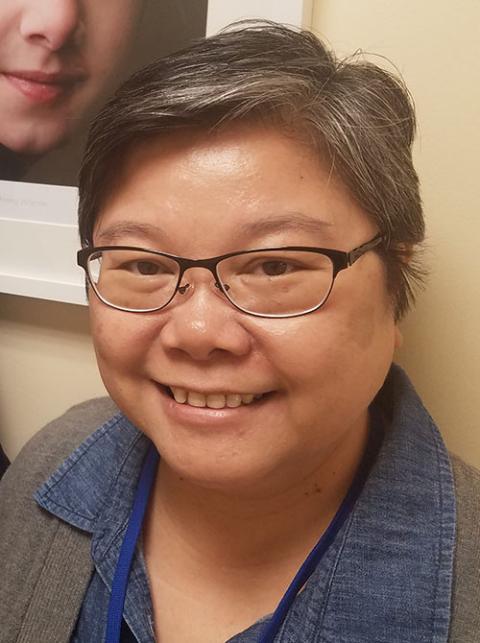

Backing the importance of that message are people such as Maryknoll Sr. Marvie Misolas, a representative of the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns at the United Nations.

Maryknoll Sr. Marvie Misolas, representative of the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns at the U.N. (GSR file photo)

"The stakes are incredibly high," Misolas said in a recent interview, noting that lifestyles, particularly in the global north, undergirded by a food system dependent on the high use of fossil fuels, are ultimately unsustainable. "Our lifestyles have consequences for the planet," she said.

One of the many groups making similar arguments is the environmental organization Greenpeace, which notes that industrial mass production of meat "is the single biggest cause of deforestation globally."

It notes that the "climate impact of meat is enormous — roughly equivalent to all the driving and flying of every car, truck and plane in the world. When forests are destroyed to produce industrial meat, billions of tons of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere, accelerating global warming."

These trends were just starting to seep into public consciousness when I began reporting on food issues more than three decades ago on a newspaper in rural Minnesota where farming was the bread and butter — literally — of the community. Raising concerns about issues of food systems was often seen as fringe or extreme.

Fortunately, there is a growing and welcome shift in public awareness about the need to make changes. I know from personal experience and travel that even in more conservative states like Florida, it's not unusual to find markets and restaurants that now make "local sourcing" of food a priority.

"I think we can make the shift," Misolas said of food justice, but it won't happen unless "there's greater environmental awareness and that will come about only through more environmental education."

Catholic Relief Services staff provide emergency assistance in Madagascar. The African country has been seriously affected by drought in the last five years. (Catholic Relief Services/Jim Stipe)

Such education, Misolas said, is grounded in a wider vision of concern for creation and the planet — what Misolas calls integral ecology, the innerconnectedness of all life.

Fortunately, Pope Francis and other leaders of the church are staking out a prophetic role on the environment, and on related issues, such as food.

The 2015 encyclical Laudato Si', Misolas said, calls all peoples of the world to a conversion — "an ecological awareness of how you and I are impacting the world because of our lifestyle."

Food awareness is a key part of that process, said Misolas' Maryknoll colleague Fr. Kenneth Thesing, who was born on a farm in Lewiston, Minnesota, and whose ministry has included a long stint in Tanzania focused on agriculture.

Thesing, who is based in Rome, was a recent online observer at the U.N.'s Food Systems Summit, a one-day event held on Sept. 23 at which the world body sought to bring together different groups in order "to transform the way the world produces, consumes and thinks about food."

Secretary-General António Guterres, seated between flags, opens the 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit on Sept. 23 at U.N. Headquarters in New York. (U.N. photo/Eskinder Debebe)

However, the event proved controversial. Many grassroots groups boycotted the summit because they felt it gave too much of a platform to corporate farming interests. Even Michael Fakhri, the U.N.'s special rapporteur on the right to food, wrote in The Guardian that the summit "offered people nothing to help overcome their daily struggles to feed themselves and their families."

In an interview, Thesing said he remained involved as a participant because it is important that groups like Maryknoll be engaged in dialogue about possible solutions. But he said the summit probably did not go far enough in asking the essential question of why too many people in the world remain hungry.

Too often, he said, the question is answered with "produce more food." But the world is producing more food than ever before, he said. "The biggest challenge remains poverty. The issue is access to food. People don't have the money to buy food."

A related problem is that in countries like Tanzania, small farmers can't compete in the market with the influx of so much imported product from large producers like the United States. "They just can't compete, and leave farming," Thesing said. And that leaves them and small rural communities increasingly impoverished.

Is there hope? Wei thinks there is. She said such links are now becoming clearer to people and prompting the beginnings of action.

Deacon Bob Hornacek, center, helps unload boxes of lettuce and other produce from a pallet and onto a cart for Paul's Pantry in Green Bay, Wisconsin, Sept. 16. (CNS/The Compass/Sam Lucero)

The Biden administration has committed to spending $10 billion "to promote food systems transformation through innovation and climate-smart agriculture," the White House said recently.

And humanitarian groups like CRS continue long-standing programs committed to empower small-scale farmers in the rural global south, as do congregations like the Maryknoll sisters, whose work in Guatemala and East Timor includes a focus on "agroecology" projects, Misolas said.

"I think people are serious about this issue," said Wei, and that may also be linked to the effects of the pandemic — of knowing neighbors who have lost jobs becoming dependent on local food pantries. "People are really seeing hunger in their communities," she said.

Given such developments, let's hope World Food Day offers a moment of reflection and hope, reminding all of us that, as the U.N. says, we "need to be part of the change."