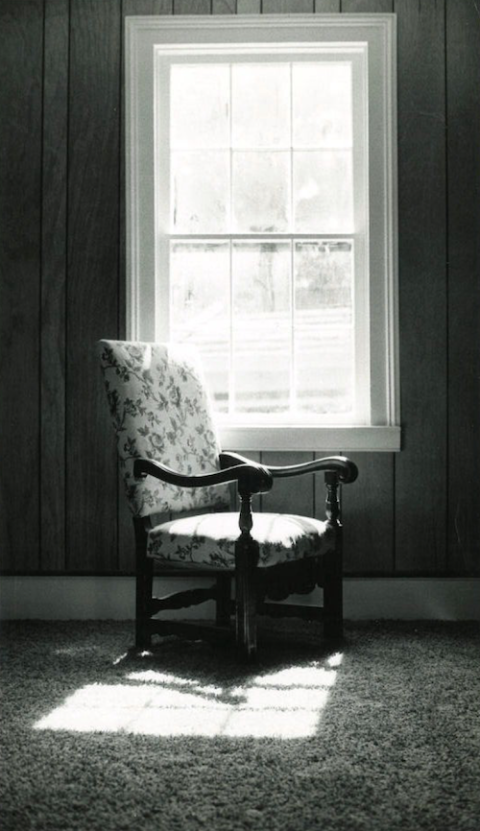

Some days the quality of light pours through the window like the quality of mercy — thick, gold, like honey in your mouth. And your mouth rejoices. Other days the light is thin and brittle. It has no depth. When it hits the furniture, it shatters in shards all over the floor. (Joan Sauro)

Teach me to care and not to care.

Teach me to sit still.

—T. S. Eliot, "Ash Wednesday"

Some days the quality of light pours through the window like the quality of mercy — thick, gold, like honey in your mouth. And your mouth rejoices.

Other days the light is thin and brittle. It has no depth. When it hits the furniture, it shatters in shards all over the floor.

Light or no light, you try to keep that tricky balance of caring and not caring as you go about your good and useful work.

One day a thin envelope of light with very good news comes sliding under your door, and your hands fill with light as you sit in the chair and read.

You're still reading, when sunlight fills the window, transforming it into the thin veil that hangs between you and the divine. You try to discern who lies beyond the window in light and shadow. Who are those figures?

But the window is mysterious, does not give up its secrets easily.

Then one day, unpredictable and unexpected, the figures slowly take shape, clear enough so there's no mistaking who they are.

Advertisement

It is your mother sitting near a window in a pitch-black room. The window is dark, looking out onto a pitch-black street. It is wartime and you are 6, your brothers, 4 and 2. The three of you are wrapped around your mother's legs, her arms wrapped around you. Now and then your mother dares a look out the window for signs of your father, her husband out patrolling dark streets while air raid sirens scream.

Wrapped around your mother's legs, the three of you are the reason your father is not on the draft list, out patrolling local streets instead of bombing enemy camps. He is out in the night with no flashlight. No weapon. His naturalization papers close to his heart. His eyes are alert for any movement, any suspicious shadow.

All the mothers and children are shut up in their dark apartments, watching through dark windows. This is every war with the men gone and the women left with children watching from windows or huddled in the blown out remains of cellars.

(Joan Sauro)

But three small children with their arms around their mother's legs are safe, keeping her safe, keeping the moment safe, the night when their father was out in the dark somewhere and lived to come home.

Then, just as mysteriously as they appeared, the figures fade in the window. And new figures take their place, even as you watch.

Early morning, the dog walkers appear, first one, then another, keeping wide, coronavirus distances from each other. Down one side of the street, up the other, and the sun barely rising.

There are small dogs with fast feet and large dogs the color of their owner's blonde bun. A tall man with military bearing and no dog strides with hat down, mask up, hands in pockets, every day the same time. One after the other the walkers pass by in the window. Be sure of this, you are not the only watcher. Heaven watches, as well.

Mid-morning, the streets are quiet, the walkers and dogs back home into quarantine.

In slow time, light appears, tentative, cautious, at first, then glorious. It washes the neighborhood, washes your room, baptizes the chair and you in it, until you are filled with light — you, the window, the memories, and the world beyond the window, all filled with light, so there's no sitting still no matter the chair. No matter the poet's advice to care and not care. Truth be known, you care, a lot.

You get up out of the chair, follow the light, and enter the window with honey in your mouth, mercy in your heart.