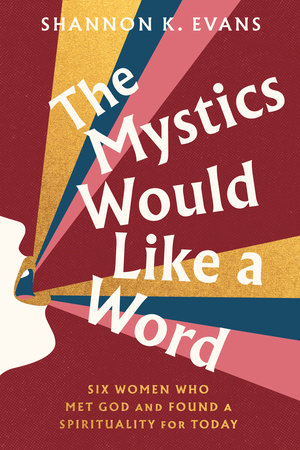

Illustrations of the six Catholic female mystics in history from The Mystics Would Like a Word, written by Shannon K. Evans, NCR culture and spirituality editor. The illustrations are clockwise, from upper left, St. Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, St. Hildegard of Bingen, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, St. Teresa of Avila and St. Catherine of Siena. (Illustrations by Dani/andhersaints)

Editor's note: This article has been adapted from The Mystics Would Like a Word (Convergent Books, 2024).

I'll admit it: History has never been my strong suit. And, as far as my faith goes, medieval saints just never carried much weight with me.

Maybe it's because of the way female saints are offered to Catholic women as role models: always presented as docile and meek, untouchable and pious, women who can teach us about speaking in humility but not about speaking truth to power. It's hard to relate to someone you can't see yourself reflected in — and might not even want to. But that all changed a few years ago, when I found myself disillusioned with modern Christian leadership and searching for guides on a more ancient path.

Once I dipped my toes into the waters of the female mystics, I realized this was the pool I'd been looking for all along. Once I read their own words, speaking for themselves in their own books, I realized that the traditional presentation of the female saints and mystics had historically been funneled through and crafted for the male gaze. What's more, I realized that in my snobbery of assuming they had nothing to teach me, I was complicit in our collective reduction of who these women were and what they had to say.

Advertisement

It turns out, these women are the furthest thing from one-dimensional, despite how they have been portrayed. They are not irrelevant or demurring, nor are they fragile. These are women who are self-determining, stubborn, opinionated, gutsy and unapologetically themselves.

As my spiritual love affair with these women evolved, I found myself shocked at how progressive their musings were and how timely they feel at this particular moment in history. Can we refer to God in the feminine? How does mental illness inform our spiritual experience? Should we keep politics out of church? What do we do with this pesky sexuality? These women had something to say.

So gradually, I began to do what we writers always do: I put my findings into words.

Starting with Teresa of Avila, then Julian of Norwich, then Hildegard of Bingen, Margery Kempe, Catherine of Siena, and finally, after some resistance, Thérèse of Lisieux, I studied the books of six of the most noteworthy Catholic female mystics in history and crafted explanations of their impact on me into a book of my own, titling it The Mystics Would Like a Word.

Teresa of Avila taught me about trusting one's inner light, as well as about the interconnection between sexuality and spirituality.

Margery Kempe taught me that mental illness has the dignity of prophetic vision, as well as about the importance of self-belonging.

Hildegard of Bingen taught me that environmental justice relies on spirituality, as well as the necessity of art-making in a broken world.

(Illustrations by Dani/andhersaints)

Five out of the six featured in this book were avowed religious, and despite my earliest prejudices, their vocation was not because they were docile but precisely because they weren't. I learned that convents were historically life rafts for women who eschewed the dutiful existence of marriage and motherhood — not to mention the high probability of death through childbirth.

In the convent, a woman could retain her agency and bodily autonomy. She could devote herself to her theological passions. Often, she could receive an education. It is no coincidence that some of the strongest female voices in history have been those of professed religious sisters, which is still true in the Catholic Church today. The only laywoman in this book is Margery Kempe, a mother of 14 who wrestled mightily with the tension between her vocation as wife and mother and her spiritual calling to prayer and teaching.

As interest in feminine spirituality is piqued around the world, we would be remiss to ignore (or worse, water down) the guides we've already been given. We don't have to reinvent the wheel.

Julian of Norwich taught me of an invitation to relate to God as Mother, as well as to prioritize love over ideas of sin and hell.

Thérèse of Lisieux taught me that insignificance is subversive, as well as how to acknowledge and comfort one's inner child.

Catherine of Siena taught me to balance action with contemplation, as well as the necessity of facing our fears and shadows.

(Illustrations by Dani/andhersaints)

There is a reason the writings of these women have stood the test of time and reverberated across centuries. May we honor them as ancestors. May we have the maturity to recognize the timelessness of their wisdom, even as we build on and expand it so many years later.

After all, we too can be mystics; for a mystic is really just someone who has experienced a glimpse of the eternal and has devoted themselves to pursuing more. Only one lifetime ago, the Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner said, "The Christian of the future will either be a mystic or will not exist." Maybe the future is now.