Firefighters walk amid rubble near the base of the destroyed south tower of the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. (CNS/Reuters)

Editor's note: This blog post was updated on Sept. 10 with comments from Sr. Mary Catherine Redmond.

The recent collapse of the Afghan government and the subsequent tragic exodus from Kabul has a strange full-circle element to it as we approach the 20th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks on the United States.

Readers may recall that a few months back, I wrote about the worry I and others with experiences in Afghanistan continue to have about the risk posed to women and girls with the Taliban takeover. (When I wrote the piece in May, I had not thought the takeover, though probably inevitable, would be as sudden as it was.)

But back in September 2001, my worries centered on what a likely U.S.-led war in Afghanistan would mean for Afghan civilians. After spending several weeks in July 2001 traveling across Afghanistan with European and Afghan colleagues to chronicle a little-reported drought, I knew firsthand the Taliban-controlled country was in a fragile state.

I didn't oppose toppling the Taliban, which had harbored al-Qaida, the militant group behind the 9/11 attacks. I certainly didn't like what I saw in Afghanistan in 2001, particularly the harmful, medieval-like restrictions on women and girls as well as on culture and free speech. But as someone who had seen parts of Kabul reduced to rubble from years of a vicious internecine conflict, the thought of yet another war in Afghanistan, however justified, was, from a humanitarian standpoint, dismaying to say the least.

So, when 9/11 happened, my firsthand experiences in Afghanistan got mixed in with my own reactions as an American and a New York City resident — reactions that were all over the map. I was shocked, saddened and angered.

First, let me recount some of the memories as a New Yorker.

One is that it was a beautiful day in New York City. We'd had a bout of hot and humid weather that stretched into September, and that Tuesday proved a relief: cool, bright and clear. It was primary election day in the city, and after I voted in the early morning, I headed from Brooklyn to my work at the offices of an international humanitarian organization in Manhattan.

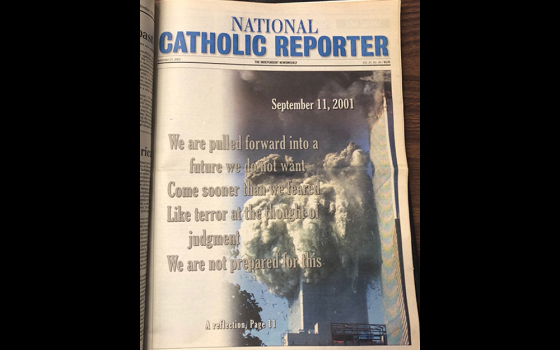

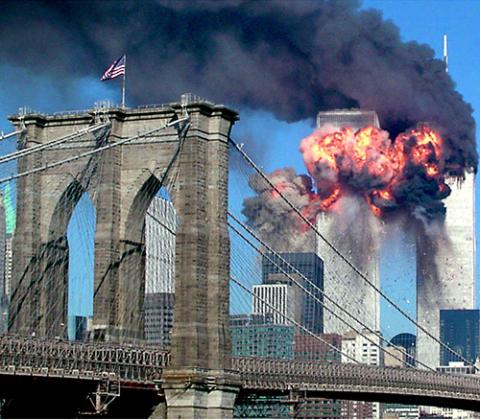

Both towers of the World Trade Center in New York City burn after planes crashed into them Sept. 11, 2001. In the foreground is the Brooklyn Bridge. (CNS/Reuters/Sara K. Schwittek)

The fact it was primary day may have spared me from witnessing the planes crash into the World Trade Center's twin towers. Some mornings, I walked across the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan with a clear and commanding view of downtown. But that morning, I chose not to, as voting that morning was going to make me late to work.

Soon after I arrived at the office, a startled colleague said in a loud voice that she had heard on the radio that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. We all assumed, I think, that it must have been a small aircraft.

But as we huddled into a conference room and watched events unfold on television, it was clear that what we were witnessing was a catastrophe. I can still remember how surreal it was, in particular, to watch the collapse of the buildings themselves.

I had attended an afternoon party in New Jersey just two days earlier and remembered how imposing the twin towers looked in the setting sun that Sunday afternoon as my friends and I took the bus back into the city. The towers were massive. And tall. It just didn't seem possible that they could actually collapse.

My colleagues and I all felt dazed, and we were given the rest of the day off, though I stayed a bit to catch my breath and teared up a bit from the many phone calls and emails from friends and family. Are you OK? Where are you? I was touched and moved by their concern and worry.

By some miracle, the often-fickle New York City subway system proved its durability, as if to say even this tragedy would not knock the city off-course. But I do recall that the train into Brooklyn slowed to a crawl as we moved underground to where the buildings, now reduced to tons of smoking rubble, had once stood.

The stench of debris, fire, smoke and, sadly, human remains would be apparent underground for weeks afterward.

Cars smolder on a street in the Wall Street district after the World Trade Center in New York was hit by two hijacked airliners Sept. 11, 2001. (CNS/Reuters)

When I finally made it into Brooklyn, the area near where I lived seemed like an image of London during the Blitz. Smoke from the downed buildings had wafted across the East River and had settled into downtown Brooklyn. Papers flew through the streets. Whether they were from the downed buildings, I don't know, but it seemed unsafe and even scandalous to find out.

In the days to come, I wrote several pieces about what it felt like to be in New York City at the time as it became a place of mourning and grieving. A draft of one of the pieces I wrote, which eventually appeared for Religion News Service but which seems to be lost to a 20-year-old internet burial site, stirs up old memories:

Two days after the attack, hundreds of residents of the borough of Brooklyn gathered on a promenade in Brooklyn Heights overlooking lower Manhattan. Smoke from the destroyed towers remained visible; candles gave the gathering a degree of warmth and comfort, but it was hard not to notice the eerie darkness: the towers had once lit up the night sky.

At a war memorial, a group of Mexican women gathered: they had brought a statue of the Virgin Mary and wrapped it in the American flag. They offered benedictions in Spanish.

Some in the crowd wanted to sing; "We Shall Overcome," "Amazing Grace" and "America the Beautiful" become standards. Others moved away from the singing, preferring time to contemplate quietly.

The next night, in the Hell's Kitchen area of midtown Manhattan, people lit candles in a collective remembrance.

Restaurant owners and patrons stepped out to the sidewalk. At one corner, Afghan Muslims held candles and watched a young gay couple embrace; a young Mexican busboy lit a candle and placed it on the sidewalk. War planes flew overhead.

By then, many were already sporting red, white and blue ribbons on their shirts and blouses; New Yorkers — often seen by other Americans as something apart and different from the rest of the country — had become the most visible symbols of a nation grieving.

In the weeks and days ahead, attention turned to the war in Afghanistan, which, in its aim of removing the Taliban, was relatively and mercifully quick.

Was I happy about that? I suppose, though I never got over the feeling that such a war would prove harmful to an already-tattered and wounded country.

When I returned to Afghanistan the next year, there was some optimism that a space had opened up for good things, like women's rights.

Boys and girls share a classroom in 2008 in Kabul, Afghanistan, at a rehabilitation center for youths who have experienced trauma and violence. (Church World Service/Chris Herlinger)

But when I returned to Afghanistan in 2007, I recalled an observation I made in a 2003 piece for the National Catholic Reporter: "Civil society and central government remain fragile ... threatened by both a lack of strong international support and the continued strength of local warlords and religious fundamentalists."

There was always something unsettled about the situation in Afghanistan, and it was folly to think outsiders could impose and then sustain the changes many Westerners like myself (and not a few Afghanis) thought were good.

And I never liked the us-versus-them dynamic that marked the triumphalism after the Taliban fell in late 2001. It smacked of imperial hubris, and that was a dynamic that undergirded the subsequent 20 years in Afghanistan. (Though let me be clear: I honor the courage and sacrifice of the young Americans who served their country during the war.)

Several sisters I know through my work in New York have similar feelings and reflections. Sr. Mary Petrosky of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary was not in New York City on 9/11 but had worked in the city for many years, both before and after 2001.

"I do know how upset I was" as she watched events unfold from Georgia, where she lived and worked at the time, she recalled.

Sr. Mary Catherine Redmond, a Sister of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary who was in New York City on 9/11, said she continues to have "a lot of mixed feelings about 9-11, as I hold the tragedy of the experience as well as the tragedy of 'us versus them' that continues in our world."

Advertisement

And Irish Sr. Jean Quinn, the Daughter of Wisdom who serves as executive director of UNANIMA International, a United Nations-based coalition of Catholic congregations focused on concerns of women, children, migrants and the environment, felt the effects of 9/11 across the ocean in Dublin.

"For many of us, the terrible events of September the 11th 2001 have become the background noise of history," she wrote in an email to me earlier this week. "The sense of trauma will never go away, of scars that will possibly never heal but ones we must live with."

"Every home in Ireland stopped in horror and disbelief as did my own, as my brother lived and worked in New York," Quinn said.

She said the aftereffects of 9/11 are similar to the trauma she saw in her work in Northern Ireland and with children experiencing homelessness.

"The emotional impact destroys a sense of security for the child, where their lived experience is one of violence," Quinn said. "In remembering this time what I remember most is the smells and especially the smell of fear."

Such fear is what now confronts many people in Afghanistan, where the 20th anniversary of 9/11 probably means little in the face of that country's unresolved tragedy.

What can be done now that we're back where we started, with the Taliban in control? Quinn said advocacy groups like UNANIMA must continue to affirm the ongoing struggle for human dignity, especially the dignity of women and girls in Afghanistan.

"We continue to emphasize the value of human rights for all," she told me.

Redmond echoed that sentiment, saying in an email she and other sisters continue "to seek ways of bridging the polarities of our church and world as I believe that is the call of the gospel. We are called to promote healing, seek justice and hold reverently the human dignity of all people."

In this moment of sorrow and remembrance, that's the least we can do to honor all of those who died in the shadow of that terrible day 20 years ago.