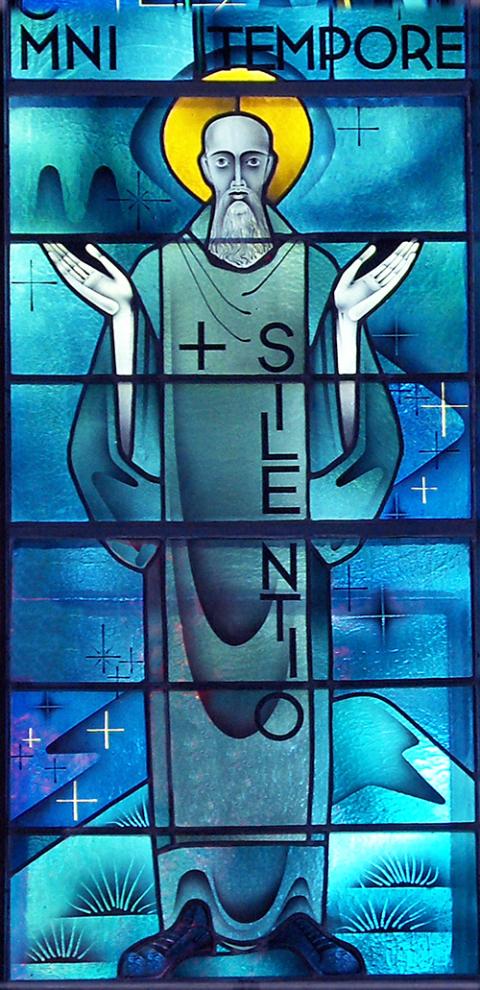

Photos of stained-glass windows in the choir chapel of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery, where the in-person portion of the colloquium "Benedictine Life: A Vision Unfolding" was held. (Courtesy of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery, Atchison, Kansas)

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two reflections about the 100th Anniversary of the Federation of St. Scholastica. See the other one here.

Portions of this column previously appeared on a post by the author on Medium.

Conventional wisdom would have it that monastic life is a hopeless throwback to the past — a case of "let the last monk or sister standing turn out the lights." Anyone who attended a recent conference on "Benedictine Life: A Vision Unfolding" would come away with a much different impression. The event commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Federation of St. Scholastica, a union of 17 Benedictine women's monasteries. The focus wasn't so much on the past as on the next 100 years.

The 250 sisters, lay associates of monasteries and spiritual seekers in attendance, came away with a message: the Benedictine tradition has lasted 1,500 years because it understands the timeless yearnings of human nature. It is not likely to fade away in a few decades — despite the current paucity of monastic vocations.

If there is one characteristic that accounts for monasticism's endurance, it is likely its ability to adapt to the current time, or as keynote speaker Sr. Judith Sutera put it, to do "the next right thing necessary at a particular time." Today, the energy in monastic life is coming largely from laypeople drawn to the timeless values of community, hospitality, humility, stability, simplicity, balance, consensus, prayer and praise that monasticism stands for. For the first time in history, the number of monastic oblates — lay associates like myself — far outnumber professed monks and sisters. It is part of what Katie Gordon, a 30-year-old staff member of the MonasteriesoftheHeart.org website and another of the conference speakers, calls "the monastic impulse."

As Sister Judith further observed, "There will never be a time when the world does not need prayer and stable community, reverence for all people and things, humility, and cooperation in relationships. This is the immovable foundation from which [Benedictine life] springs."

The sisters of the Federation of St. Scholastica (renamed at their June meeting the "Monastic Congregation of St. Scholastica") view this liminal moment in their history as a launching pad for renewal. Organizations rarely escape a period of diminishment. There is generally a start-up period, a time of growth, an inevitable plateau, and then, often, decline. Decline, however, isn’t failure. It is a moment when renewal can begin.

Sisters are drawing guidance from several current models for confronting organizational change. The process of "emergence" arose many times in conference conversations. Unlike traditional strategic planning that involves deciding upon an end result and then moving toward it with intentional steps, the emergence process represents a more organic, evolutionary method.

"It gives us instead the promise of surprise," says Sister Edith Bogue, a sociologist from Sacred Heart Monastery in Cullman, Alabama, who spoke on "The Way Forward."

Photos of stained-glass windows in the choir chapel of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery, where the in-person portion of the colloquium "Benedictine Life: A Vision Unfolding" was held. (Courtesy of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery, Atchison, Kansas)

"Emergence" recognizes that momentous change occurs in increments. It involves taking risks, experimenting, and being willing to abandon some experiments. It requires the repeated asking of "What if?" questions as well as, "What and who might help to move us along?"

It also necessitates what Sister Edith calls "unlearning," the courage to let go of previous patterns of thinking that no longer prove useful or effective. This is where the practice of humility —an integral value to the monastic impulse — comes in. Humility allows us to acknowledge that none of us individually possesses the whole truth. Humility gives us permission to admit that we might have been wrong in our previous thinking.

Sister Edith offers the image of a Native American kiva, a dark, silent, underground space. In its midst is a ladder reaching toward the light above — reminiscent of "the ladder of humility" in The Rule of St. Benedict. After spending time in reflection and meditation in the kiva, it becomes possible to climb out of one’s inner darkness and confusion toward a more enlightened place — what Sister Edith describes as "the womb from which we emerge with new resilience."

Native American elder and former Anglican bishop Steven Charleston describes the kiva experience in his book Ladder to the Light. He writes, "Let this moment of darkness be the beginning of your next journey in faith. Help others find the ladder. … And once you are there — once you have emerged into the world we are recreating — join the dance. Beneath the bright shining sun, join the dance and let the healing begin."

Already new models of monastic life are taking shape. There are currently dispersed communities in which members might live and work in different cities but share a common rule and come together online for common prayer times. The Pax Priory is one example. Ecumenical communities also exist, such as Holy Wisdom Monastery in Madison, Wisconsin, as well as ones in which families and those vowed to the celibate life live and pray together in community.

Increasingly, oblates are living full-time in monasteries and sharing deeply in the life of the community. Some monasteries have opened their doors to those willing to spend a specified period of time in the community without the expectation that they will one day take permanent vows.

This is not to say transformation into the next phase of monastic life will be swift or easy. Sister Judith reminds us of a motto of the early Federation leaders: "Make haste, slowly."

Advertisement

To move on to a new chapter will require the cooperation of several different personalities. The Berkana Institute has done research on what happens when an institution transitions from decline to revitalization. Their model also applies to religious institutions. According to this model, some in a community will become "originators," people capable of envisioning a new future, ready to forge on. Others will take on the role of "stabilizers," those who wish to have things remain as they are. Yet, they help remind a community of what is worth keeping. Stabilizers need the aid of "hospice workers" within the community who can help ease the discomfort of those struggling with changes.

Perhaps the largest segment in any community facing transition can be described as "wave riders." Like surfers, they sense the movement taking place under them and try their best to keep their balance.

While change is inevitable, one of the most important functions of monastic life must not and will not change: that of bearing witness. Deborah Asberry, an executive coach with CommunityWorks, Inc. of Indianapolis and another of the keynote speakers, observed that the monastic witness is at its heart twofold: to speak the truth in a society often lost in illusion, and to bring hope to those in despair.

Like monasteries, our society as a whole is facing rapid changes from greater diversity in our citizenry to calls for increased inclusivity and racial justice and new ways of looking at gender and sexuality. We as a society would do well to follow the lead of the Benedictine sisters of the Monastic Federation of St. Scholastica in seeking to embrace transformation. Their gaze is on the past, but their minds are on the future.