Sr. Anne Montgomery, a member of the Christian Peacemakers Team, reads outside the "Witness Against Torture" camp at the military zone boundary near the U.S. detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Dec. 13, 2005. (CNS/Reuters)

A self-described "Navy brat," Sr. Anne Montgomery was born in 1926, the second child and only daughter of a rear admiral who fought in World War II.

She joined the Religious of the Sacred Heart at a young age and for years taught poetry and literature at Catholic schools in New York. Time spent teaching inner-city youth of color educated her in the rapaciousness of U.S. militarism, its theft of domestic resources from the poor. By 1980, peace activism had become her full-time ministry.

A petite woman, Montgomery possessed ferocious courage. At age 83, she participated in the last of her eight Plowshares actions for nuclear disarmament, each one an attempt to embody the prophet Isaiah's call to "beat swords into plowshares," each one requiring an arrest, trial, and imprisonment or probation.

Determined to be with the people "who have the biggest guns pointed at them," she joined numerous civilian peacekeeping initiatives, traveling to Iraq and the Balkans and later serving with Christian Peacemakers Team (now Community Peacemaker Teams) in the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

Laconic in demeanor, Montgomery articulated with searing precision what compelled her peace activism. The Scriptures, of course, but also a keen sense of the legal perversions that justify violence.

Plowshares actions are not an expression of "civil disobedience," but "divine obedience," she wrote. "The term 'disobedience' is not appropriate, because any law that does not protect life is no real law. In particular, both divine and international law tell us that weapons of mass destruction are a crime against humanity and it is the duty of the ordinary citizen to actively oppose them."

Catholic Worker Art Laffin first met Montgomery in 1978 while he was fasting outside the United Nations for nuclear disarmament. The two would go on to participate in two Plowshares actions together and to co-edit a history of the Plowshares movement. Laffin said he knew his friend was a "great writer," but he did not discover the range of her poetic capacity until after her death in 2012. At her funeral, members of Montgomery's order handed him a manila folder of her poetry.

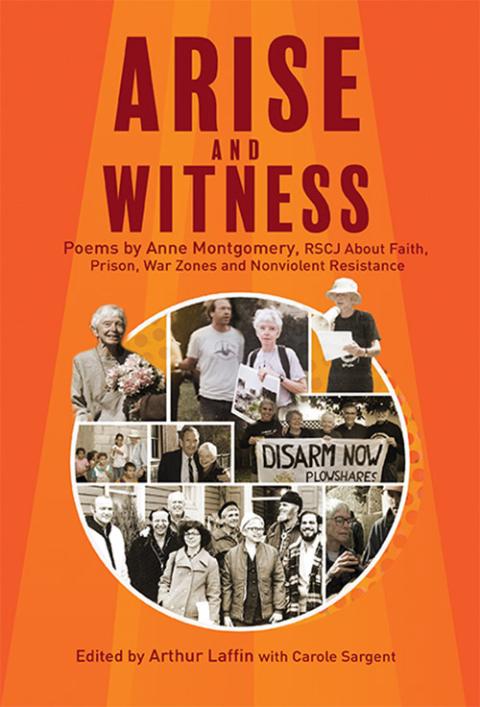

Arise and Witness: Poems by Anne Montgomery, RSCJ, About Faith, Prison, War Zones and Nonviolent Resistance, which Laffin edited in collaboration with editor and writer Carole Sargent, a Religious of the Sacred Heart associate, now brings those poems to light.

Also included are talks by Montgomery, a short biography of her remarkable life and reflections from those who knew her. Collectively, the texts reveal a woman who, in her activism and verse, relied on metaphor, paradox and symbol to articulate faith in the God of life amid a disbelieving world.

Global Sisters Report sat down with Laffin and Sargent to talk about their book. The following is an edited version of the interview.

GSR: There are many biblical references in these poems and also a remarkable contemplative energy. As somebody who knew Anne, did it surprise you to see this quiet dynamism coming out on the page?

Laffin: Anne had a profound depth of understanding the Scripture and what it means for us now. These poems were manifestations of her insights into the Scripture. We used for the book's prologue an essay by Anne entitled "Facing the Darkness." (The text opens with the first two stanzas of Denise Levertov's "Making Peace.")

In it, Anne explains the meaning of her poetry herself. ... [She writes]:

John's gospel introduces Jesus as the Light of the World, overcoming a darkness which cannot comprehend his way of nonviolent love, of no compromise with the political and religious power brokers of his time.

In poetic metaphor and symbol, he consistently spoke, "the grammar of justice." But he spoke most clearly and dangerously by his life, offering not immediate results, but a Way of fidelity to truth speaking, in love of both friends and enemies, a "syntax of mutual aid."

In our Plowshares community, we tried to speak the language of pilgrimage, of the way being the goal.

I witnessed that up close. She was very committed to the process, to the way of trying to do something. And if it could happen, fine.

In the Thames River Plowshares action, she didn't reach the Trident submarine. She got to the pier right near the Trident and she was rescued by the Coast Guard, because she was one of the swimmers. She was very cold, and they had to put blankets around her. It was the way she speaks about it, the process. The end is contained in the means which we use.

Do you see Anne's poetry as trying to articulate the mystery of a process prose cannot fully capture? Her poems are laden with paradox, and there is an implicit paradox in peace, right? People are stepping into the fire of human suffering instead of fleeing. Do you think her poems were a way of trying to figure this out?

Laffin: I do. When I first met her, it was two years before the [1980] Plowshares 8 action happened. I was living in New Haven [Connecticut] at the time.

Sr. Anne Montgomery, left, who participated in six Plowshares actions to protest nuclear weapons between 1980 and 2009, is pictured with Holy Child Jesus Sr. Megan Rice in a 2010 photo. (CNS/Courtesy of Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action)

When I saw that Anne was involved, it didn't surprise me a bit. The more I got to know her, I felt she had this depth of faith, which was just profound. I learned a lot from her, and as I said earlier, I knew she was a writer. I think that the poetry she was writing came out of her prayer and her lived experience of resistance in community. And that it was a way for her to process for herself what was taking place.

Sargent: I wrote a chapter about Anne Montgomery for the Plowshares book, because [Holy Child Jesus] Sr. Megan Rice said, if you wanted to understand her, you had to know Anne Montgomery first. Anne was her model and her inspiration for the actions that she did. So I studied Anne's life and did interviews with people who knew her family.

Her father was a pretty rigid guy. He was a military commander. I don't know how rigid he was in the household. They didn't really talk about him being abusive or anything like that. But he suffered from migraines, and they were absolutely brutal.

All of her RSCJ sisters said that Anne wasn't a big talker. She didn't unburden herself about how she felt about an action. She was a pretty contained soul.

We need to tread lightly, or not at all, if we try to psychoanalyze people through their writing. So I don't try to say, "Oh, this was her way of letting out feelings." I have no idea. But I do know from her family and from testimony that she didn't emote in a ton of other ways.

I'm guessing, and this is just a guess, that the poetry was a way for her to deal with emotion that she didn't tend to express in other ways.

Your collection includes a prose piece titled "Solidarity with the Victims: Return Trip to Iraq." How do you think Anne's poems amplified her theology of solidarity?

Laffin: I went to Hebron to visit Anne four times when I was part of the campaign to free Mordechai Vanunu (Israeli nuclear whistleblower). I made it a point to visit her each time I went to the Holy Land.

The Christian Peacemaker Team had this little kind of apartment space in Hebron, and that's where Anne lived for a number of years. She would go there for different stretches of time. She was beloved by the Palestinian people in Hebron. I was really touched by it.

And she was so courageous. I went with her, accompanying a family to an area where the settlers were constantly threatening and engaging in belligerent behavior toward this one family. These settlers were just seething with hatred. (On one of them, I saw a Yankees hat, I think was from Brooklyn, New York.) And they said, "This land belongs to the sons of Israel, you know."

[The Palestinian family] was trying to go to their land and see how their olive grove and fig trees were faring. And the settlers came out with their guns. Anne was just so clear and nonviolent.

She knew why she was there. It's like a line from one of [Jesuit Fr.] Dan [Berrigan]'s poems, "Know where you stand and stand there." She knew where she stood, and she just didn't have any qualms about doing what she was doing. This was the right thing to do.

Advertisement

Anne went from Plowshares actions to prison, where she was accompanying women, another expression of her solidarity. She was able to rebound and recover from prison experience and then go into the war zone, and then back to doing a Plowshares action, prison, and then back to the war zone, and so on. It was a remarkable witness in solidarity when you really think about it.

Encountering her in her poetry posthumously must give you a deeper understanding of the source of her courage.

Laffin: At the feast of the Holy Innocents [Dec. 28], we [Catholic Workers] have a witness at the Pentagon. I came across her poem "Feast of the Innocents 1991/In Memoriam: Mass Graves," and we read that every year now at the Pentagon.

It's so rich and there's such depth to it. It helps me personally understand why we need to keep going back to the Pentagon in a spirit of nonviolence and resistance to the war-making empire.

That's interesting because movement language can be ideological, if not propagandistic. It's intended to arouse people to action. Whereas the language of poetry is often more paradoxical, more subtle. Yet it too can arouse people in different ways. It sounds like this collection has been sustaining and urging you along.

Laffin: Well, I can't call Anne up anymore or be with her, so this is the next best thing — reading what she wrote. She was never despairing that I can recall, really.

There's this part in her poem about the mass graves, which was written in 1991, right in the immediate aftermath of the 42 days of bombing in Iraq, and she says, just listen to this, "The year's death reminds us of an old story, a nightmare that will not go away, but, dragon-like, rises from the sea, blinds the dawn, blasphemes God's name and dwelling with fire from heaven on those, uncounted, who do not count."

What a statement! There's the recognition of the victims, the nameless victims, but also what witnessing means and the new hope that it can give birth to in our actions.

Do you see these poems as maybe a manual for recovering our humanness, in the sense that to be human is to know we are made in the image of God?

Laffin: Absolutely. There is this resurrection hope that is inspired by her faith, which I think is something we all desperately need. I came up with the book's title, Arise and Witness, while reading the first poem in this collection, "Christ Is Risen and He Walks." We have to arise. To do what we can to be a witness to Gospel nonviolence is the only way out of the culture of violence. And we have to experiment in the truth. ... Our actions, as Gandhi said, are experiments in truth.

And we have to keep doing that. But to face the fear of the unknown, the despair, the violence, the suffering, the imprisonment, the victims, you need hope. And where does that hope come from but in an understanding of the Resurrection. I think Anne tries to convey that in a lot of her poems.