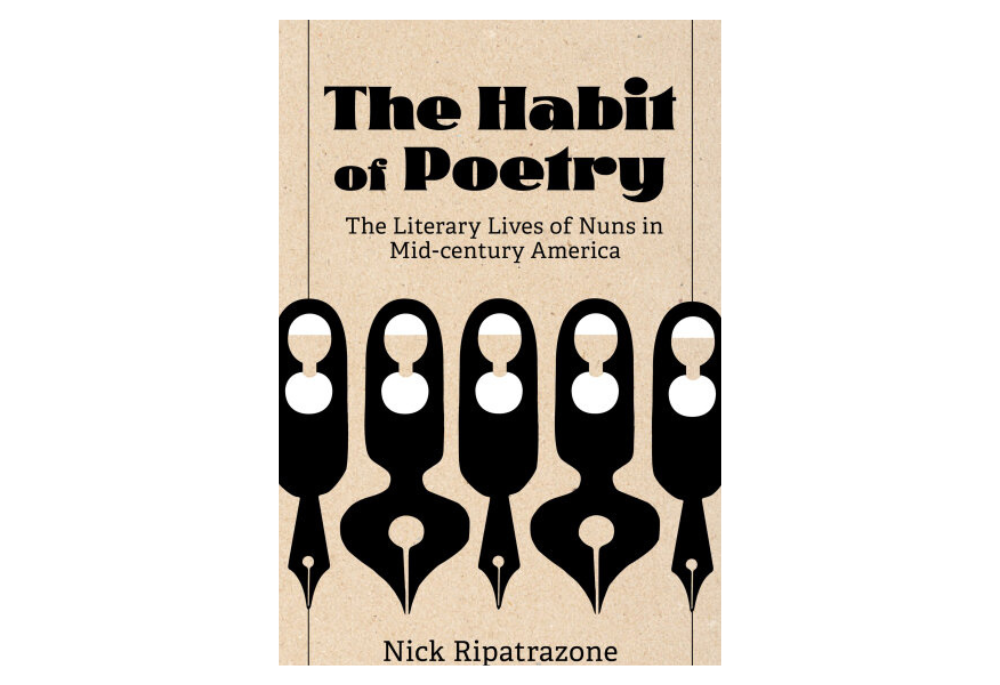

(GSR/Courtesy of Fortress Press)

Author Nick Ripatrazone's The Habit of Poetry: The Literary Lives of Nuns in Mid-century America, published this year by Fortress Press, examines the contributions of sisters to American letters and poetry. It is a compact but thorough look at the lives and works of six sisters who were acclaimed for poetry that appeared in secular venues, such as the Atlantic Monthly, Poetry and Sewanee Review, as well as more avowedly Catholic publications, such as America.

Ripatrazone affirms the sisters' distinct paths at a time when literary culture in the U.S. was flourishing. For these sisters, "poetry was the language of their hearts and minds, and the most perfect way to ponder belief and doubt," Ripatrazone writes.

While the book's focus is on the sisters' poetry, Ripatrazone notes the sisters' relationship — much of it through letters — with their literary contemporaries, including Flannery O'Connor, Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton, Wallace Stevens and John Berryman.

In the book's conclusion, Ripatrazone notes that Madeleva Wolff, Jessica Powers, Mary Bernetta Quinn, Madeline DeFrees, Maura Eichner and Mary Francis did not represent a "monolithic school" of poetry.

"They were women of varying talents, personalities, and regions. Some were contemplatives; others were teachers. Yet all of them were poets," he writes.

"Their poetry was syntactically skilled, stylistically ambitious, and rooted in the paradoxes of belief. These Catholic women wrote and published poetry at a time when nuns and sisters were fighting for respect and support."

In being published "alongside the finest secular poets of their day," they also received their peers' respect and admiration. "Theirs was an artistic renaissance in mid-century America: a recognition that nuns and sisters could create complex representations of life and love. Their work is significant. And the lives of these nuns and sisters are models for artists who wish to sing of doubt and belief," Ripatrazone argues.

In addition to teaching at a public school in New Jersey, Ripatrazone has also taught literature and writing at Rutgers University, where he received a master of fine arts in fiction writing. He is the cultural editor of Image Journal, a contributing editor at The Millions and a columnist for Literary Hub.

GSR: What drew you to this topic?

Ripatrazone: I often write about the archives of literary journals. For example, if I write about Don DeLillo or Thomas Pynchon, I'm really interested in how those major writers evolved. So, I'll go into the back issues of the Kenyon Review or some other literary publication to see when those writers started publishing their short stories.

Since I spent a lot of time looking through those archives, as I was looking at other writers, I started to notice "Sister this," "Mother this," in those magazines. It just kind of was surprising to me, not in the sense that these women weren't intelligent or literary; it was just in secular publications you don't see that very often. I saw it enough in my meandering through those archives that I started to look for it directly. I noticed that they were publishing consistently and they were being celebrated, and it was something that stood out. I think that's really what opened my eyes to this.

So, I started looking up their poetry and seeing what had been written about them, and there wasn't much. I noticed that one of the women, Sr. Quinn, was an incredibly prolific letter writer with basically a laundry list of the best writers of her generation: Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, like anybody who is everybody. They wrote to her as if she was almost like a spiritual guide, but also a literary companion. And that's when it showed to me something was really up at this time.

You say early in the book that when it came to sisters and poetry in midcentury America, "something was happening." What do you think was happening? How would you characterize it?

In midcentury America, which I would expand from the 1930s to the 1970s, American nuns and sisters were publishing consistently in the "highest" American poetry publications, the places that the major American writers at that time were publishing in.

It wasn't as if there would be a poem here or there, and it was just sort of a fluke. They were consistently publishing poetry. They were publishing literary criticism. Some of them were even publishing fiction, even though my book is, of course, focused on their poetry. So, they were publishing smart, significant, risky work in the high-tier secular journals, and that was an unusual thing.

Sr. Mary Madeleva Wolff is one of six American nuns and sisters whose poetry is highlighted in a new book, The Habit of Poetry. (Courtesy of St. Mary's College)

In your book you note that Thomas Merton said that because of Sr. Madeleva Wolff, people in religious orders, both men and women, were able to publish in secular venues. It seems like this debt has not been acknowledged or recorded until this book.

I think that Merton's relationship with literary sisters hasn't been really investigated fully. What I discovered while reading his letters to them is that he recognized their talent. I think it is a part of American Catholic intellectual tradition that hasn't really been investigated, in a certain way. We have in Catholic circles a great understanding of Gerard Manley Hopkins, the (19th-century British) Jesuit priest who was a poet, and he's sort of held up as the great exemplar of a Catholic religious who was also an artist. But I think with women religious, there's the question of why hasn't the Catholic intellectual tradition noticed them and sort of recognized their worth?

So, with Merton, his intersection with their world in a way brings some measure of, I don't want to say he validates them because they don't need it, but he gives them sort of name recognition by being someone who was friends with them, who sought their input. Sr. Wolff read Merton's work, corresponded with him. In a way, it's good to have his name in the mix because it shows that a very significant American writer at the time who was Catholic and who was a religious also recognized their worth.

What do you think the Catholic literary sensibility was and is?

I think in a very kind of Catholic literary sensibility, it represents what being a cultural Catholic is. [Writers] might use the symbolism of the church. They might kind of build off of the symbolism of Mass or liturgy, but they tend to embed it in personal experience, and they tend to write far more often about sinners than saints, that it's not a purely devotional kind of literature. It's a literature that is very sensory-driven, that is very in the weeds, so to speak. It's very messy and morally ambiguous, but ultimately it's really suffused with a sense of hope and a sense of optimism about the world.

I think what I, certainly as a reader, look for is writers who feel culturally Catholic rather than doctrinaire. One of the women portrayed here, Sr. Maura Eichner, would be writing satirical poems. They're very progressive and very, very surprising. But you could tell, based on her allusions, based on her references that she came to that world from a Catholic point of view.

One thing that was striking through the examples you gave of the poetry, is that much of the poetry is not overtly about religion, that they were dealing with secular topics and weren't always employing religious symbolism. Am I reading that correctly?

That's definitely true. They were not exclusively dogmatic. They were not exclusively biblical. In fact, when they made biblical allusions, they did so in very dynamic and fresh ways.

There seems to be a tradition of what I would call Christian sentimentality — making religious symbols and images sentimental. But the sisters you cite seemed to really step away from that — they really believed that craft and critical facility were more important than being overtly pious.

Yes. I think that demonstrates the seriousness of their art form and the fact that Madeline DeFrees, who was Sr. Mary Gilbert, but she left the order, I believe, in the mid '70s or late '60s, was placing as a finalist in secular book awards; she was studying with poet John Berryman. These are women who are very averse to what you accurately describe as the Christian sentimental vision, which it's problematic for a serious artist to just point to the dogma as the justification for the art. They worked their way up from the ground floor, and they did so without sentimentality.

Do you think the sisters that you profiled were comfortable in that tension between crafting poetry and remaining true to their religious life?

I think at least Sr. Mary Gilbert saw at some point that the tension was indicative or representative of something else in her existence, that she joined the order when she was very young, I think 16 or 17. She talks in her poetry about how it was her mom who sort of nudged her in that direction. So, I think for at least one of the women, the tension became exemplary of other things in their existence that they were wrangling with spiritually.

But I think the women who remained sisters and nuns found in that tension a generative element. I think in literary history, we see if a writer is pious without doubt, or if a writer is absolutely antithetical to religion. Those polarities don't often create great, complex literature. A lot of times, it's the writer who has a predilection for belief, but maybe some measure of worldly skepticism. That interplay tends to create the most nuanced works of literature or art. So, I feel the women were in a great position to have that spiritual wrangling while remaining very much committed as believers.