(Unsplash/Nathan Dumlao)

The humanities are in peril. In the last few years, several colleges and universities have shut down the humanities and redirected money toward the STEM disciplines, citing changing demographics, online education, financial constraints and a selective job market. The Catholic college or university finds itself in the same competitive sphere of higher education as its secular counterparts: jobs, attractive majors, tuition costs and online courses are changing the matrix of higher education. Does the Catholic college or university have anything distinctive to offer to today's world?

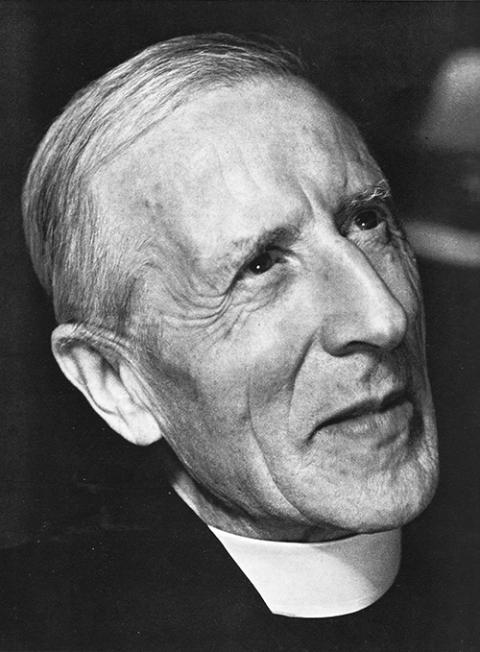

Jesuit Fr. John Courtney Murray was keenly aware of the critical role Catholic higher education could play in secular society and warned against a narrow Catholicism that could deaden the spirit. The purpose of Catholic education, he said, is not to shrink the soul but to widen its capacity for the unity of truth.

Massimo Faggioli's new book, Theology and Catholic Higher Education: Beyond Our Identity Crisis, raises serious concerns about the future of Catholic universities. He warns that the pursuit of global market competitiveness threatens their fundamental mission of teaching Catholic faith and advancing God's kingdom through social justice, environmental care and human dignity. While Faggioli brings significant expertise as an ecclesiologist and Vatican II scholar, his analysis reveals important limitations.

By closely aligning theological work with ecclesiastical authority, he risks constraining theology's broader mission of "faith seeking understanding" in our complex cultural landscape. His examination of the 1967 Land O'Lakes conference at Notre Dame reveals his deeper concern, a departure from the Aristotelian-Thomistic synthesis of faith and reason. His defense of Catholic higher education remains anchored in a mid-20th century ecclesiological framework that suffers from crucial definitional ambiguities, particularly regarding the terms "catholic" and "theology." His prescriptive vision for Catholic theology departments assumes a one-size-fits-all model that, ironically, could accelerate their decline rather than ensure their survival.

French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin is seen in this 1947 photo. (OSV News/Archives des Jesuits de France via public domain)

My two decades of work in science and religion have led me to approach Catholic theology through the lenses of cosmology and philosophy, echoing how theology developed before the Council of Nicea (A.D. 325). Theology is inherently dynamic and historically embedded; attempting to constrain it within rigid institutional boundaries inevitably distorts its natural evolution. Contemporary Catholic theology has struggled to engage meaningfully with modern science, maintaining an uneasy distance from evolutionary theory. It has largely remained anchored in Aristotelian philosophical principles and medieval Thomistic metaphysics, functioning more as a "rearview mirror" discipline than a forward-looking enterprise.

Yet if we accept the medieval notion that philosophy serves as theology's handmaid, then in our postmodern context, science must be recognized as philosophy's mother. The Jesuit scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin recognized this crucial insight, warning that Christianity risks irrelevance if it fails to align itself with evolution. Indeed, he viewed evolution as a fundamental theoretical framework to which all sciences and knowledge must ultimately conform.

Jesuit Fr. John Haughey offered a more nuanced approach to Catholic higher education in his 2009 book, Where is Knowing Going? The Horizons of the Knowing Subject, which he began with a careful examination of the epistemological foundations of the word "catholic." Haughey explained that "catholicity" inherently suggests openness and universality, standing in contrast to the partial, sectarian or exclusive. The term's Greek roots — "kata" (preposition) and "holos" (noun) combine to form kath' holou — literally mean "wholly," while "katholikos" translates to "catholicity." This etymology emphasizes movement toward universality and wholeness, providing a framework where both Catholic and non-Catholic scholars can participate in the academic pursuit of knowledge.

Building on Jesuit Fr. Bernard Lonergan's insights into notional being, intentionality and consciousness, Haughey developed catholicity as an epistemology, a particular way of knowing that sacralizes the world, as it seeks to build up the body of Christ. This dynamic engagement of mind and heart prevents Catholic theology from becoming merely a mechanism for filling empty minds, like cardboard boxes, with outdated doctrines. Instead, as Haughey suggests, Catholic theology manifests as the work of God's spirit groaning through us, as creation yearns for its fulfillment (cf. Romans 8:22). In this light, the theological enterprise becomes less about defending medieval ideas and more akin to the creative process of childbirth.

This dynamic engagement of mind and heart prevents Catholic theology from becoming merely a mechanism for filling empty minds, like cardboard boxes, with outdated doctrines.

Haughey's contribution extends beyond Faggioli's emphasis on strengthening ties between academic theology and the institutional church. Instead, he reimagines theology as a universal quest for wholeness, open to all scholars regardless of religious affiliation. His focus shifts from "Catholic" to "catholicity," distinguishing the Catholic intellectual tradition from its doctrinal tradition, and looking forward to what higher education — both Catholic and secular — can become. Rather than lamenting a romanticized past, he envisions the future potential of both Catholic and secular higher education. His epistemology of catholicity extends beyond theological inquiry to embrace all university disciplines, grounding itself in incarnational subjectivity while seeking comprehensive meaning through the Holy Spirit's influence on human intentionality.

As Teilhard de Chardin observed, thinking itself is a unifying act that brings coherence to fragmentation. This cognitive process reflects both human and divine Spirit, actively engaging mind with world. In this vision, the pursuit of knowledge serves not to defend the church against change but to nurture its growth as the consciously christified body portion of the world. While Faggioli's analysis of Catholic higher education demonstrates deep knowledge of Vatican II, it ultimately fails to offer meaningful solutions to contemporary challenges. His perspective remains anchored in the past, showing little engagement with the profound technological and scientific developments that shape our current reality.

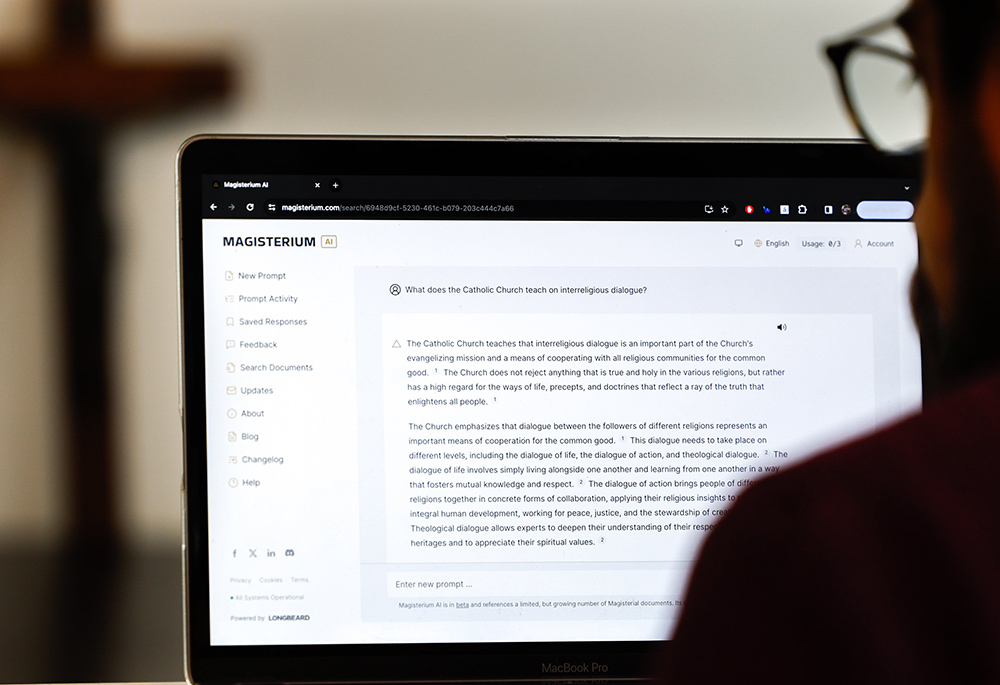

A person uses MagisteriumAI, an artificial intelligence system trained to provide answers about the teachings of the Catholic Church, in this illustration photo taken in Rome April 23, 2024. The development of large language models, generative AI systems and robotic-assistant learning are already fundamentally altering the educational landscape, writes Ilia Delio. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

If Catholic theology is to remain viable as a discipline of deepening faith, then it must engage with evolution and quantum physics as the primary drivers of change. More specifically, complexity and consciousness are reshaping our understanding of reality. Artificial intelligence, or AI, reflects a new layer of evolution, the level of mind or noosphere, which will continue to grow and affect all aspects of human life, including Catholic higher education. The noosphere is bringing about what some call "the global brain." The development of large language models (for example, the work of OpenAI), generative AI systems and robotic-assistant learning are already fundamentally altering the educational landscape. Higher education institutions find themselves in an environment of profound digital disruption.

The humanities cannot remain isolated from these reconstituted learning environments mediated by digital networks, implantable devices and robotic assistants. Just as smart systems have transformed our homes and offices, intelligent technologies will revolutionize our educational spaces, creating entirely new paradigms for teaching and learning.

Advertisement

Can Catholic theology keep pace in a world of rapid change? Faggioli correctly anticipates the potential decline of theology departments; however, his diagnosis misses the core issue. The real threat comes not from liberal theology but from Catholic theology's reluctance to engage with God's ongoing creative activity in a world increasingly shaped by science and technology.

The real threat comes not from liberal theology but from Catholic theology's reluctance to engage with God's ongoing creative activity in a world increasingly shaped by science and technology.

The future of Catholic theology lies not in historical preservation or ecclesiocentrism but in dynamic engagement with an evolving world of intrinsic connectivity, complex systems and emerging life. The driving principles of evolution — creativity, novelty and future — are fundamentally biblical principles. God does not have a plan, God has a vision, as Alfred Whitehead wrote.

As God's creative love propels us into an unprecedented future, the question becomes increasingly urgent: Will Catholic theology find itself left behind, waiting at an empty station while the train of evolution moves forward? If God's desire is to make all things new, as Scripture proclaims, then theology must ground itself not in what has been, but in what is becoming.

Theology can do no other than rest on the future.