(File photos)

Dear readers, where did 2019 go? Every year seems faster than the one before it.

(Or perhaps that's just because it was my first full year as a mom. Most weeks, especially when he was a newborn early in the year, are a blur.)

Luckily, not everything about 2019 was a blur. Take these 10 stories published on Global Sisters Report, for example. Each had something about it that has stuck with me and is worth revisiting, or enjoying for the first time if you missed it earlier in the year.

We have some exciting projects in the works for 2020 that we can't wait to share with you. Happy New Year, and thanks for reading GSR. We love you.

Ghana sister rescues disabled children viewed as bad omens in their villages by Doreen Ajiambo, published Nov. 18

Sr. Stan Therese Mumuni poses for a photo surrounded by children at Nazareth Home for God's Children in northern Ghana. (Doreen Ajiambo)

In some parts of Ghana, children born with physical and mental disabilities are considered bad omens for their families and society. These "spirit children" are blamed for deaths, failed harvests, poverty, famine and more. This heart-wrenching story focuses on the Nazareth Home for God's Children, run by Sr. Stan Therese Mumuni, who rescues children who have been given poison and left to die or cast out from their homes.

"My parents rejected me," one 12-year-old girl told Doreen. "They called me a witch because I could not speak. I thank the church and Sister for saving my life."

Ghana has an estimated 2.8 million people with mental disabilities. Of those, 650,000 have some type of mental disorder. But the country has only three psychiatric hospitals, a fact that takes my breath away.

Nuns and Nones: Unlikely partners tackle the big questions by Soli Salgado, published Feb. 4

From left: Alan Webb, Sarah Bradley, Dominican Sr. Gloria Jones and Adam Horowitz, part of Nuns and Nones (Provided by Sr. Gloria Jones)

We had published some columns from sisters about Nuns and Nones, but we wanted to write more in-depth about the coming together of sisters and young people who identify as "nones" — shorthand for the box they check next to "religion" on forms. Soli was happy to interview those involved and write about the ongoing partnership between women religious and millennials seeking meaning, following them throughout the year.

She learned that what drives the "nones" — a passion for social justice, desire for authentic community, hunger for contemplative practice, and a willingness to devote their lives to a greater purpose — reminds sisters of their younger selves.

"In some ways, I see them as the modern religious congregation," one sister said. "Certainly not the same, but the basics and the desires are there."

Sisters support Nigeria's migrants traumatized by trafficking by Patrick Egwu, published May 30

Sr. Bibiana Emenaha of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul speaks to students in February at a rural school in Edo, Nigeria, on the dangers of trafficking. (Courtesy of the Committee for the Support of Dignity of Women)

Since 1999, the Committee for the Support of Dignity of Women in Nigeria has helped Nigerian women who have been trafficked out of the country return home and reintegrate into their old lives.

"We make them feel at home here and take them in as members of our family," said Sr. Bibiana Emenaha, the committee's coordinator.

Emenaha and two other Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul provide professional counseling to returnees and visit schools to create awareness on the dangers of trafficking. Their work is part of an international effort to stop human trafficking, one of the major issues Global Sisters Report focused on in 2019, the 10th anniversary of the founding of Talitha Kum. The international anti-trafficking network of religious held its first general assembly in Rome in September.

Death never has the last word, and sisters never die alone by Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans, published June 3

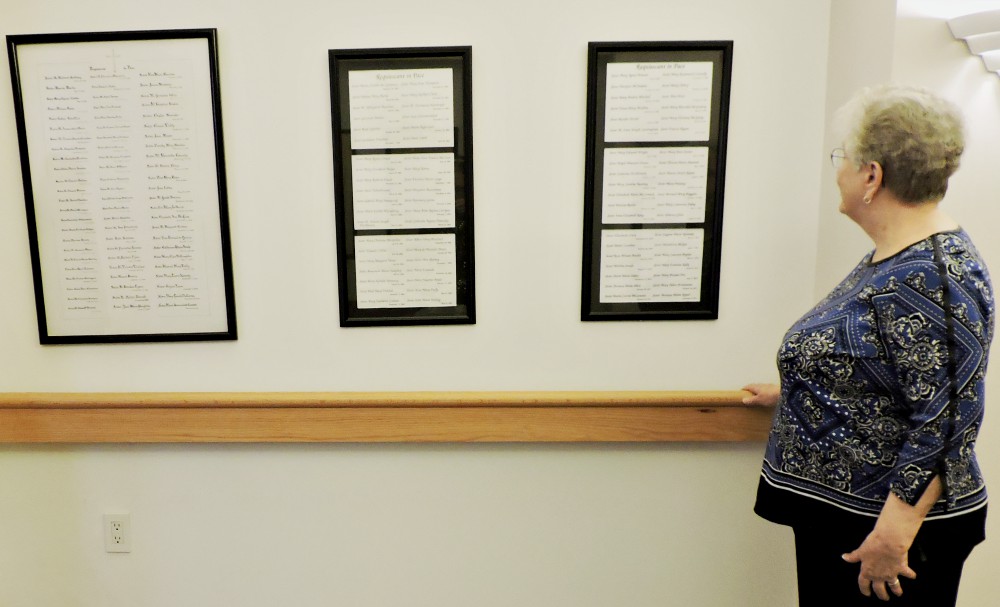

Sr. Marie Michele Donnelly surveys the names of sisters memorialized outside the chapel at the Convent of Mercy in Merion, Pennsylvania. (Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans)

Some religious communities encourage sisters to plan their own funerals, including the prayers and hymns they would like included. Others enlist friends and family in planning for death.

"It's not something we fear. Dying well is just part of our lives."

Those two sentences from a Daughter of St. Paul summarize exactly what Elizabeth found in interviewing multiple sisters about death and dying for her two-part series, "A Good Death." In Part 1, sisters explained how communities address the death of a member. Part 2 profiled two sisters who face the possibility of death daily.

(As a side note, Part 1 also features one of my favorite opening paragraphs in a story from the last year.)

Nuns on healing mission in Sri Lanka help Easter Sunday bombing victims regain normalcy by Thomas Scaria, published July 1

The church healing mission team does a quick evaluation before moving to another family affected by the bombings on Easter Sunday in Negombo, Sri Lanka. (Thomas Scaria)

On Easter Sunday, coordinated bombings killed at least 250 people in churches, hotels and other sites across Sri Lanka. Thomas traveled to Negombo, a Christian enclave, in the aftermath to learn how sisters were helping those who had been injured or lost family and friends. Some sisters reached out to give aid as soon as immediately after word of the bombs spread.

The nuns helped the survivors in three stages, visiting first families who lost "their dear and near ones," then families of those who were severely injured, and finally the rest of the parishioners. They did what they could in the face of grief, providing psychological support.

"Even after such a terrible experience, most families have accepted the tragedy and surrendered to God's will," one sister told Thomas at the time.

The sisters of Holmes County, Mississippi, integral to the community by Dan Stockman, published Oct. 14

Sr. Madeline Kavanaugh, a Daughter of Charity, laughs with Marvin Edwards on Sept. 12 in Durant, Mississippi. Kavanaugh and Edwards run a statewide re-entry program for inmates being released from Mississippi prisons to prepare them for life after incarceration. (GSR photo / Dan Stockman)

Dan had long wanted to visit Holmes County, where Srs. Paula Merrill and Margaret Held lived and died, but the logistics were tricky. He finally made it to Mississippi in September, and the story he wrote spoke of a community trying to move forward after the sisters' murder.

"When something like that happens to people of that caliber, it has a big effect on society," the city manager of Durant told him.

Advertisement

Dan's story focuses on the three new sisters who moved to Durant, Srs. Sheila Conley, Mary Waltz and Madeline Kavanaugh, all of whom continue the mission to help the residents in a poor part of the state. But what surprised him was how Merrill and Held continued to be a part of the story.

"No matter where I went in the humid Mississippi heat, Paula and Margaret seemed inescapable," he wrote in a blog post afterward. "Everyone I interviewed talked about them, though I didn't ask."

Child workers in Vietnam stay safer knowing labor rights, self-defense tactics by Joachim Pham, published March 21

Nguyen Thi Tien, 15, left, sells fruit on a road near An Lo market in Thua Thien Hue Province. At a workshop run by the Filles de Marie Immaculée sisters in Hue City, Vietnam, Tien was trained in how to deal with abusive adult customers. (Joachim Pham)

A 14-year-old girl is selling salted peanuts and baked rice paper at an open-air bar in Hue City, Vietnam, when a man touches her hand, making her uncomfortable. She signals to her friends, also selling food nearby, who swarm the man and his friends, loudly asking him to buy food. Flustered, the man buys some peanuts and chases the kids off.

The girl and her friends learned the tactic from the Filles de Marie Immaculée, who hold special workshops to teach child workers, orphans and other at-risk children what to do in uncomfortable, and potentially dangerous, situations. The workshops also empower the children by teaching them how to work in groups, receive health care and advocate for themselves in a work environment.

"I have phone numbers of some Catholic volunteers, social workers and fellows to call them in case I am bullied, abused or unfairly treated, so I no longer fear strangers," a 15-year-old fruit-seller told Joachim.

Amid Salvadoran gang violence, sisters strive to shepherd at-risk youth by Chris Herlinger, published Nov. 21

People are seen outside the home shared by three Sacred Heart sisters in La Chacra, on the outskirts of San Salvador, an economically depressed area and vulnerable to violence in El Salvador. (Chris Herlinger)

While Chris was on his reporting trip to El Salvador, he spent time with sisters who minister in neighborhoods rife with gang activity, where it's not unusual to hear gunshots. Healing the wounds of violence and offering support for communities affected by gang activity are at the heart of ministries run by sisters there, such as a youth center in Apopa, which Chris also wrote about in another story from the country.

"We feel so safe here. So safe. So great," a 16-year-old who plays soccer at the center told him.

The sisters are a bright spot among the stories of tragedy. Despite the violence, the gang members respect the sisters, who take a pastoral approach, even allowing gang members to use one community's school basketball courts.

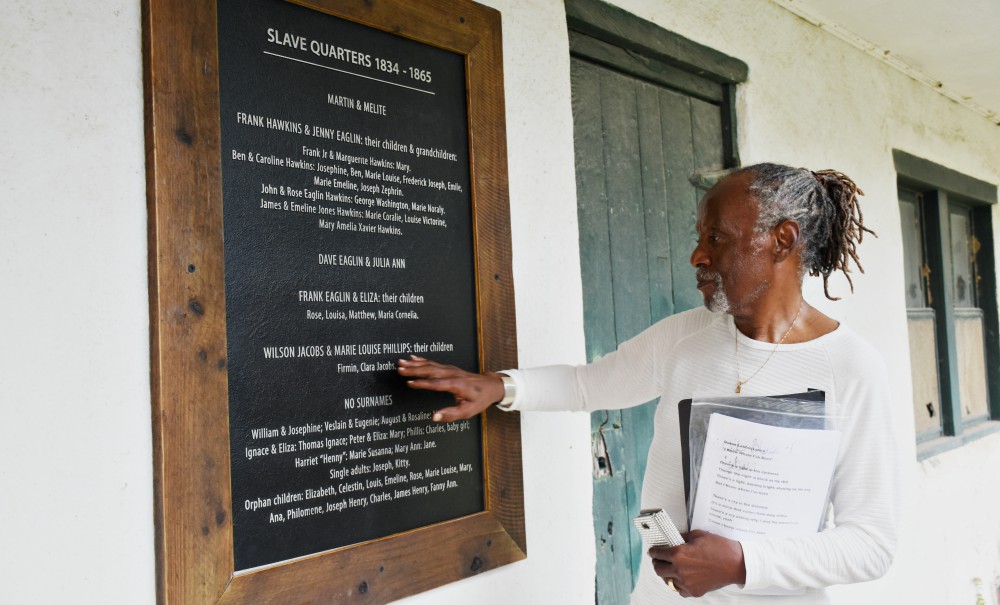

Descendants of enslaved people find their roots in Sacred Heart records by Dawn Araujo-Hawkins, published Sept. 12

During a 2018 memorial event, Dorson William Purdy Jr., one of the descendants of the enslaved people of the Society of the Sacred Heart in Grand Coteau, Louisiana, looks at a newly installed plaque on the former slave quarters, which remain on the sisters' property. (Society of the Sacred Heart/Linda Behrens)

In 2016, the United States and Canadian province of the Society of the Sacred Heart convened a Committee on Slavery, Accountability and Reconciliation and gave it a two-year mandate to "recover the story of slavery in our early days in this country." Part of the mission: tracking down the descendants of the more than 150 black people whose forced labor was used to build and maintain Sacred Heart properties.

The sisters' sacramental records, turned into family trees the sisters posted on Ancestry.com, helped descendants learn more about their enslaved ancestors and led to a September 2018 event, "We Speak Your Names," to honor them.

One sister told Dawn it can be hard for many white people, including women religious, to truly examine the ways they are complicit in white supremacy.

"I'm a descendant of German farmers," she said. "My people did not enslave people but, still, there's a collective identity of white privilege. And becoming aware of that can be a frightening experience."

Welcome of the heart: Sisters build bonds in collaborative effort to assist immigrants by Nuri Vallbona, published Aug. 1

Sr. Jean Durel helps Cyrilo Garcia, left, his son, Kelvin Naum, 3, and Juan Jose Nuñez pinpoint their departure time June 18 at the San Antonio Greyhound station. (Nuri Vallbona)

About 1,000 sisters in states on the U.S.-Mexico border have been ministering to immigrants seeking safety in the United States since a surge began in fall 2018. Some help at temporary shelters, offer travel assistance or even send shoelaces to replace those confiscated by border agents. Others pray, donate funds or join protests.

What separates the sisters from other organizations, Nuri writes, is their ability to build relationships with those they serve as well as those in authority. The sisters are also forming closer bonds across communities.

"We are one heart," a Daughter of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul told Nuri. "The people who are not used to being around sisters, they're absolutely amazed at how we support each other; how we appreciate each other and how we care about each other."

[Pam Hackenmiller is managing editor of Global Sisters Report. Her email address is [email protected].]