Sr. Susan K. Wood has no desire to become a Lutheran. She doesn't want to see the Lutheran church "give up" and become Catholic. She doesn't want Catholics to turn into Lutherans. But she does want unity.

Wood, a theologian and Sister of Charity of Leavenworth, is the co-author of A Shared Spiritual Journey: Lutherans and Catholics Traveling Toward Unity, published August 1 by Paulist Press. Her co-author, Timothy J. Wengert, is a Lutheran historian who recently authored a commentary and study guide to Martin Luther's 95 theses.

Wood has been working on ecumenism since 1994, when the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops appointed her to the committee to review the "Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification," which was a step forward for Lutheran-Catholic relations. She has been involved in Lutheran-Catholic dialogue ever since.

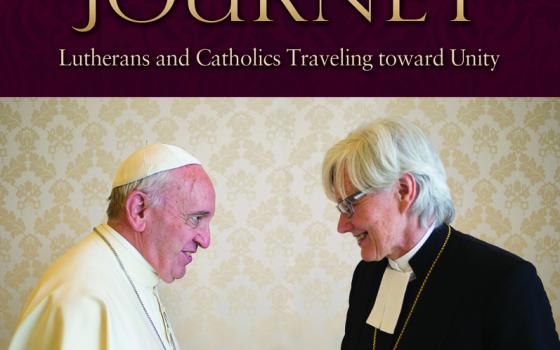

She is a professor of theology at Marquette University in Milwaukee and gave the concluding lecture at a Catholic-Lutheran international seminar in Rome in May. As a member of the Lutheran-Catholic Commission on Unity, she will attend the October 31 launch of the 500th anniversary observance of the Lutheran Reformation in Lund, Sweden, where Pope Francis will be welcomed by Lutheran Archbishop Antje Jackelén, who is pictured with Pope Francis on the cover of Wood's new book.

GSR: How did a Catholic sister end up working with a Lutheran historian on a book about ecumenical efforts between the two churches?

Wood: Actually, the publisher, Paulist Press, approached me — which never happens — because they wanted something for 2017, which is the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. At the time, I was chair of the theology department at Marquette, and it was a bit of a tight deadline. Authors never meet their deadline, but it usually doesn't make a lot of difference. But because this was up against the date of the commemoration, it mattered, so I said, 'I need a co-author.' Not only because of the deadline, but because I'm not a historian, I'm a systematic theologian. But co-authorship is a little like a marriage: You don't just jump into it.

In the meantime, the U.S. dialogue [on Lutheran-Catholic unity] had just reconvened, and Timothy Wengert was on it. That was the first time we met, but we sat next to each other and decided we could work together.

It could not have gone better. It was a fabulous experience. First, I think it's important that a book like this is co-authored. It was important to have both a Catholic and a Lutheran writing it. In fact, it was imperative.

So what is the book about? Is it about why we should be unified? Why we are not?

Well, I think that not every Lutheran, and not every Catholic for that matter, is going to agree with all of it, but I think the book shows — in ways that dialogue can't — how to find resolution for the issues that divide us. It's an optimistic presentation.

Ecumenical work is all about relationships, which is so perfectly represented by the photo on the cover of Pope Francis shaking the hand of a woman Lutheran bishop. It's a visual icon on so many levels. It's a handshake of friendship.

But it also shows one of the big divides: The elephant in the room on so many of these issues is women's ordination and . . . we're not going to cross that final divide anytime soon. Ecumenically, we're minimalist about what we say about it. What we have to tell Catholics is we recognize ordained women ministers within the Lutheran tradition.

So distinctions like that can stay in place? Because that's what a lot of people fear about ecumenism — that their beliefs won't mean anything anymore.

I think there is a real fear among a certain generation of losing their ecclesial identity. There's a desire to go back to the church of the 1950s, which they never experienced, and recover the cultural markers of the Catholic church. One of those cultural markers is to define yourself against other churches, to say, 'We're this, we're not that.'

But Catholics need to know that ecumenism was one of the four reasons that Vatican II was called. Pope John XXIII made that clear, and Paul VI reiterated it when he took over. The document on liturgy, the first document approved, mentions ecumenism in the first chapter.

A lot of people think ecumenism is just frosting on the cake, or that it means moving to the lowest common denominator, or they think we're selling out. But it doesn't.

I spoke in a parish where a lot of Lutherans and Catholics are married to each other. This is where ecumenism meets the road: They're living the effects of our division, and they're suffering for it. The parish discussion was lively, with lots of questions and back and forth. The next day, I spoke in a seminary, and there was only one question, and everyone stared him down for asking it.

So if everyone keeps their identity and beliefs, then what does ecumenism really mean?

It means recognition of the one church of Christ. It doesn't mean Lutherans become Catholics. It's not a return to the Catholic church. In ecumenical unity, you keep your ecclesial traditions, you keep your histories, and you keep your identities. The model for this is the Eastern Catholic churches and the Western Catholic churches. The Eastern Catholic churches have their own rite, their own traditions, their own histories, but they're in communion with the bishop of Rome.

That makes it sound easy. So what's keeping us apart?

Lutherans and Catholics are struggling with the same problems, but they do it with different language. So part of it is learning each other's language. The hardest thing for me in working with Lutherans was to get my head around what kind of questions make sense in that system and which questions don't.

A Catholic would ask, 'How do you fall out of justification?" And a Lutheran would scratch their head and say, 'That's an interesting question.' Because in the Lutheran world, everything is kind of an I/thou question. Their view is: 'I have to accept God's mercy. My goal is to not take my eyes off that promise.' The Catholic view is: 'What if you take your eyes off?' It's a third-person question, not an I/thou question. It's the same belief from a different perspective.

So is there hope? Will there ever be unity between the two?

I think under Pope Francis, there's a much better chance of moving forward. My sense of what Francis is doing is he's not denying or taking on a stand on the traditional disputes. He's trying to refocus the conversation.

It's like the spiritual exercises of St. Ignatius at a retreat: You go in to the spiritual director, and you think you have this problem or this issue, and you think you're going to work on this problem or this issue during the retreat. But you almost never do. Instead, the spiritual director — if they're good — refocuses you on your primary relationship with Jesus Christ, and the other things kind of resolve themselves. I think that's what Francis is trying to do. Francis' focus is on discipleship and our relationship with the Lord while we get hung up on all these other parts. He's not dismissing the differences, he's just refocusing our view. He's reprioritizing our values.

I think we need to be disciples together. We need to celebrate the faith we share together instead of protecting our turf.

The tragedy of church division is that it's like a marriage in that it's harder to mend a relationship once there is a divorce than to mend a relationship that hasn't reached the point of breaking yet. It seems like the bar we raise in order to mend that relationship is higher, and maybe it shouldn't be. Just like we raise the standard for ecumenical unity to a level that we don't even have in our own house.

You've been working on ecumenical issues for a long time. How has it changed you?

It is broadening to me to learn this other language, this language of encounter and promise. Not that I have assimilated it — I don't pretend to — but I need to incorporate that into my spiritual life and have that direct relationship. I am enriched by the Liturgy of the Word from Protestant life.

In this time of commemoration, we're remembering and telling the story of the Reformation together in a way we never have before. But at this time of remembering, we also have to have a time of forgetting, where we forget the hurt and the insults. And that translates into our personal lives, too. I think there are parallels between our personal spiritual life and the relationships between these churches.

When you get into ecumenism, you become more Catholic — I don't have any desire to become Lutheran — because you get deeper into own identity and what it means. I still think Catholic liturgy speaks to me in way Lutheran liturgy doesn't.

I think it's all about friendship, and it's all about relationship. I have a firm conviction that we need to have deep friendships with 'others' in our life, whether they an 'other' because of their faith or their culture or their lifestyle. When we do that, then we are transformed, because the relationship is more important than the difference.

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is dstockman@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]