Sex workers in their skin-tight dresses and high heels leaning on the green sidewalk barriers are a common sight along Circunvalación, one of the main thoroughfares through La Merced. (GSR photo/Tracy Barnett)

Manuela's* life was an intergenerational horror story. Born to a mother who practiced prostitution for a living, and with two older sisters who did the same, it seemed almost inevitable she'd follow the same path. Her almond eyes filled with tears as she told of clients who kidnapped, beat and robbed her, others who left without paying, and one who tried to slash her throat. She told of the painful deaths of her mother and sisters at a young age.

"With five children and me with only a middle school education — what was I to do?" she said. "I thought life was just like that, that life was abuse. Why? Because that's what I learned from my mom, to be submissive, to be the one who does everything to serve people."

But Manuela has found a different life and a different way to serve people, thanks to the sisters of the Casa Madre Antonia, a 152-year-old project to accompany and support women who earn their living in the sex trade. Casa Madre Antonia is a project of the Oblate Sisters of the Most Holy Redeemer, founded in Spain in 1870 and now celebrating 100 years in Mexico.

Today, Manuela walks those streets side-by-side with the sisters, wearing the blue vest of the Casa and offering a hand and word of encouragement to women who in other times might have been her colleagues. Manuela is one of the success stories of the Casa: Besides helping with outreach, she also produces natural medicines under a project the sisters created.

In Mexico, the congregation's work is based in La Merced, Mexico City's largest prostitution district, where sisters estimate around 3,000 women work the streets each day. For generations, a contingent of committed sisters has been reaching out to these women, providing a safe space for healing and creating a different future, serving around 450 of them on a regular basis.

The sisters use the term "women in situations of prostitution," rejecting "sex workers," which they feel normalizes a situation that should not be normalized.

Mexico is one of the top countries for sex trafficking, and while trafficked persons are generally carefully controlled and managed through organized crime networks, the sisters are occasionally called upon to intervene in trafficking cases, primarily by making referrals to designated law enforcement staff and providing moral support.

A tough mission in a chaotic commercial district fraught with shootings, robberies and assaults, it's also an exercise in acceptance, as their subjects are much more likely to continue in the streets than not.

Still, the successes are many.

Oblate Sr. María Rosas, center, teaches classic embroidery patterns and sewing techniques to two women, at the same time creating a safe space to talk about their lives. (GSR photo/Tracy Barnett)

A safe space and sense of community

The Oblate sisters' activities run the gamut, including walking the streets of La Merced doing direct outreach and hosting a variety of skills-based workshops, psychological and healing therapies, remedial classes and spiritual formation.

Part of the mission is to help the women value themselves and know their rights. Another is to provide a basic education for those who have not yet achieved that milestone, and — perhaps above all — a safe space and a sense of community.

On this typical October morning, sisters woke early to put together bags of bread and other basic food items to share with the women who would come that day.

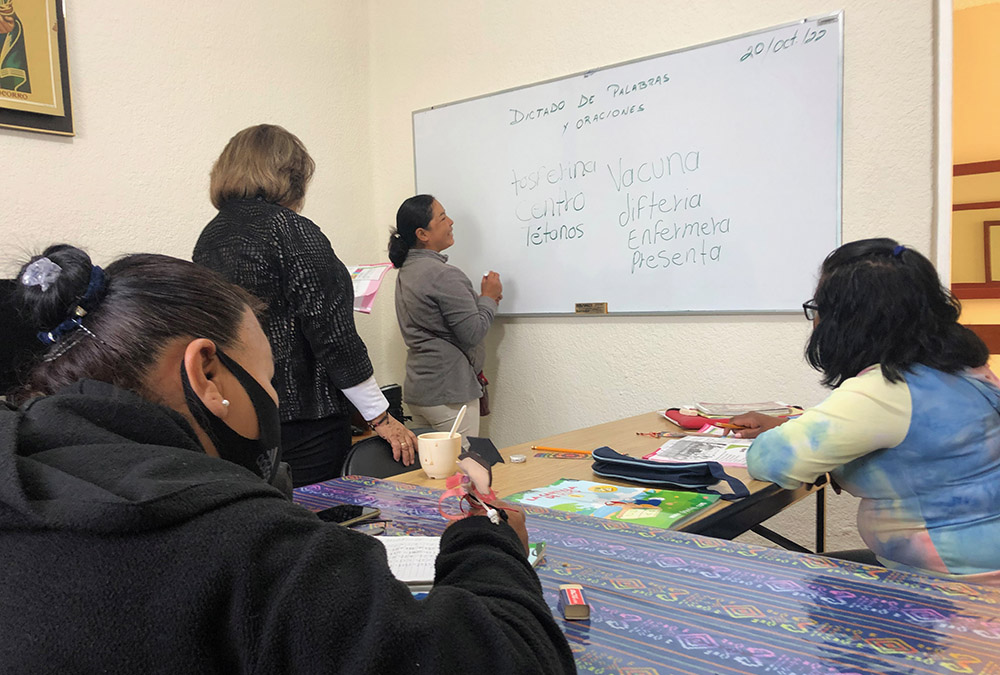

Then they divided into groups. Sr. María Rosas taught sewing and embroidery skills, an alternative source of income, as she coaxed the women into sharing their frustrations with life on the streets. Sr. Rosa Aguayo González taught the basics of reading and writing to another group.

Meanwhile, a volunteer taught the women how to convert castaway items and simple household objects into art, while Sr. Manuela Rodríguez sat with small groups around the wishing well in the garden to facilitate "spiritual formation" and an opportunity to share their own personal stories and reflections.

Josefina, who is studying to get her middle school certification, practices her vocabulary as Sr. Rosa Aguayo, behind her, and fellow students look on. (GSR photo/Tracy Barnett)

"All of our work has a teaching aspect, from the moment we go to meet them," Rodríguez said. "We greet them with great respect, observing what happens, because with those who are under pimps — or padrotes — it is more difficult.

"But on the other hand, there are those we can start a dialogue with. We are not going to condemn them, nor investigate or disrespect them, but really welcome them, like those very loved people that they are, very dear to God, highly respected as first-class citizens."

Rodríguez never ceases to be amazed at the spiritual depth of the women.

"We always start from what is very human, and as we talk, we see that they also have a great deal of God — of the sacred — in their lives," she said, adding that the differences in how each woman expresses the "sacred" is important to them.

"That sacred part is what gives so much meaning to the whole formation. They bring so much spiritual wealth, so much beautiful experience."

'We are angels, and sometimes we don't realize it ... a messenger angel who announces the breath of life with the word of God.'

—Maitena

Global Sisters Report spoke with a woman who still works the streets and goes by "Maitena," which means "the most beloved woman." Youthful for 46, she wore a flower in her hair and was pretty and fair-skinned, with a slightly fragile aspect.

"I was so ignorant when I arrived here from my village," she said of La Merced. "I thought everyone was good. ... Later, I found out it wasn't so."

Not long after her arrival in the city she learned of a day care that the sisters were running at the time. With a 2-year-old daughter, she jumped at the opportunity to send her daughter to the day care. She began learning about the other services they offered and gradually got involved.

That was 14 years ago, and since then the sisters have been a constant support through many trials, including an unplanned pregnancy.

It was a Family Constellations therapy session that awakened Maitena to understand that her way of normalizing dysfunctional behaviors came from generations past, making her determined not to pass on the same mistakes to her children, to know their rights and to help them have a strong sense of self-esteem.

"Over time it has helped me a lot, because I can see my story and understand many things."

One of Maitena's most important insights from her years working with the sisters: "We are angels, and sometimes we don't realize it ... a messenger angel who announces the breath of life with the word of God. Every hug I give someone must be part of God. Sometimes I'm wrong ... but I forgive myself, and I return with that light."

One of the women reaches for a book she decorated using the techniques she learned at Casa Madre Antonia with basic materials: crumpled tissue paper, lace and paint. (GSR photo/Tracy Barnett)

A change in theology

The congregation's theology as well as its approach has changed over the years. Whereas its foundress would speak of "the sin of the lost women," and emphasized the importance of repentance — indeed, she would refer to those they served as "repentant women" — nowadays the emphasis is on accompaniment, education and empowerment.

"The first sisters also went with that attitude of saving them, because they were the sinners who were there in the abyss, and we were the saints who were going to get them out," Rodríguez explained with a laugh. "But that theology was in response to an era. Today, it's another theology. We approach them with much respect, love, mercy. And entering their path together, we make a path of liberation.

"It is really to create a process from wherever they are," she continued. "We believe that they have the Gospel, they have God in their hearts, they have the good news; it is not that we have come to give it to them. We help them to be empowered, and together we are evangelizing."

In the early years, the emphasis was on prevention of prostitution, said Sr. Aurea Rendón, with the congregation offering residential shelters to give young women an alternative to the streets.

But over the years, she said, "we began to realize that it is very different to have houses, homes and boarding schools than it is to work directly with women in situations of prostitution."

'We approach them with much respect, love, mercy. And entering their path together, we make a path of liberation..'

—Oblate Sr. Manuela Rodríguez

In 1989, they closed their residential home and opened the Centro Madre Antonia in the heart of La Merced, though in 2022 they moved to a new location 20 minutes away. The work, however, remains the same: direct outreach to the women in the streets.

The sisters must be on high alert at all times, emphasized Rodríguez. "When we go out into the street, one has to keep all eyes on them, because many are watched, both by [the pimps] or by other people who are surveilling them. We have to be very cautious, because [a mistake] can bring reprisals for both the person and us."

Doors to future connections

On a typical afternoon, Srs. Carmen Paz, Rosas and Rodríguez gathered with a handful of volunteers and staff, including Manuela, for what they call "abordaje" — "approach" — their word for the outreach they do nearly every afternoon on these streets.

Their base in La Merced is a space in La Palmita, a 250-year-old church in the heart of the hubbub. This is where they invite the women on Tuesdays for rose petal therapy, straight from the streets, under the gentle hands of therapist Luz María Mitre. It's a therapy that moves many to tears, Mitre said, and the intimate talks afterward open the door to future connections.

The mood was upbeat as the sisters divided in pairs. Each donned a blue vest emblazoned with the logo of Centro Madre Antonia. For today's abordaje, they had prepared an icebreaker to help the women talk about their feelings: a "sopa de letras," or word search with different emotions hidden within.

Oblate Sr. Carmen Paz, second from left, is joined by staff member Mariana Gutierrez and two volunteers as they approach La Palmita, a 250-year-old church where they have their base in La Merced. (GSR photo/Tracy Barnett)

The streets throbbed with commerce: men carrying loads or pushing dollies full of boxes, shoppers filling the sidewalks looking for clothing, shoes, electronics — and, more discreetly, sex. Though it didn't feel dangerous, things can change quickly, the sisters warned.

It didn't take long for Paz to make her first connection; she hardly needed a vest. "Where have you been?" demanded a woman in a tight-fitting, wine-colored minidress and glittery eyeliner. Her eyes creasing in a smile that revealed her middle age, she reached out for a sisterly embrace. "You've been missed," she said.

Her colleagues lined up along the street, checking cellphones and leaning on posts to rest their weary high-heeled feet. They spanned the range in terms of age and appearance. Some were young, though the underaged girls who work there are under tight control, the sisters said, and don't generally agree to talk. Some were older, including an 80-year-old named Sofía. Most of the elders work in a different area, though, and suffer the worst abuses.

As Paz approached, women's faces would light up. One woman sat on a cement planter box, peering into a hand mirror and checking her makeup. "Así o más bello?" teased Paz — "Like that, or more beautiful?"

Advertisement

Victoria was a regal young woman with a tight black dress, high heels, thick lashes and long dark hair adorned with small silver rings. She was leaning on a post next to a taco stand. Food stands can be surveillance posts, as many women are carefully watched by a network that reports back to the pimp. (Her name has been changed to protect her identity.)

She was aloof at first, ironic as Paz passed her the square of paper and a pen and explained the word-search exercise, intended to help the women verbalize their emotions. Victoria scanned the page. "Alegria" (joy) and "miedo" (fear) popped out right away, and she circled them — then stalled.

"The words can be hard to find, just like real emotions," Paz explained encouragingly. "Some are obvious. But there are other emotions that lie under those, and it's worth it to go deeper. Emotions are not good or bad, but they are important: They give us signals that we need to guide us in our lives."

She pulled out the bright yellow flier that the sisters had prepared. Victoria studied the paper intently, and one by one, she outlined the words: Depression. Euphoria. Blindness. Anger.

"Yes, anger," muttered Victoria. "Like for that guy who keeps hitting me."

Traffic of all kinds is used to get around in La Merced, such as this rickshaw-like bicycle designed for carrying passengers and merchandise. (GSR photo/Tracy Barnett)

Paz listened intently. "You don't have to accept that," she quietly told the young woman. She turned over the yellow brochure and read aloud from the text, pointing to a picture of a woman with her head in her hands: "Who is there for me, who will listen to me?"

"You are not alone," she assured the young woman, handing her a list of resources the women can call for help.

She invited Victoria to the upcoming Day of the Dead party and to check out some of the Casa's many offerings, then continued on her way. At each stop, she'd offer words of encouragement and occasionally advice, inviting each of them to the Casa Madre Antonia, where they would find workshops, food, solidarity, therapy.

One woman looked wistful upon hearing of the sewing workshops. "I always wanted to learn to sew, but I don't know if I can, because of this," she said, raising her left hand, which had been injured years ago by a machete.

"Yes, you can," Paz said. "There are so many things you can do. Sewing, natural medicine, art. Come join us. You will see." She left her with an invitation to the upcoming celebration, and an embrace. The woman was smiling as she walked away.

*Name has been changed.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to alter the name of one of the sources and remove her photo to better protect her identity.