Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise García, center, at her final profession in 2010, with her mentors and sponsors, Adrian Dominican Srs. Rosemary Ferguson and Carol Coston at her sides, and Attracta Kelly, the prioress, receiving her vows. (Provided photo)

Before she surprised everyone, including herself, by becoming a sister at age 50, Elise García lived a life that, in one sense, closely resembled that of a sister: She was engaged in social justice issues, advocacy and nonprofits and had a keen lifelong concern for the fate of the planet.

But organized religion had been peripheral in her life, as her spirituality in adulthood was more grounded in nature and the cosmos. It wasn't until she met Adrian Dominican sisters in her social justice circles in the 1990s that she began to follow a mysterious call to Catholicism and religious life.

Now, García, 70, is the president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, the national organization that represents 80% of women religious in the United States. In the triumvirate presidency, she is joined by past-president Sr. Jayne Helmlinger, a Sister of St. Joseph of Orange, California, and new president-elect Sr. Jane Herb of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Monroe, Michigan, who was elected June 29, ahead of LCWR's annual assembly, held virtually Aug. 12-14.

Today, LCWR leadership overlooks an increasingly multicultural religious landscape. Younger sisters, though fewer in number, are more diverse, equipped and enthusiastic about the potential of their global sisterhood.

And García, whose upbringing spanned five countries, brings an innate appreciation for diversity to the presidency as well as perspective that comes with a mature religious formation, as she became Catholic shortly before becoming a sister.

The task before religious leadership now is to discern the varying needs of its sisters while creatively exploring how their vocation can best reshape and respond to an increasingly secular world contending with a pandemic, racial unrest, economic anxiety and ecological destruction.

And García, a former organic farmer, ethics advocate and book publisher, will be at the heart of that discernment.

Elise García, standing behind her parents with her four younger siblings in a 1964 portrait (Provided photo)

'Belonging really anywhere that you can make home'

García was born Feb. 26, 1950, in Brooklyn, New York, the oldest of five children of a Norwegian mother and Spanish father. His occupation as a diplomat took the family around the world: García lived in Mexico, Uruguay and Egypt before her senior year in high school.

Moving every three or four years was her sense of normal, she said. "I'm living the itinerant Dominican lifestyle before I knew what it meant to be a Dominican."

With half-day English, half-day Spanish schooling growing up, García said she was exposed to issues around identity at a young age, as well as differing perspectives on history.

"I've now in my later years grown to really understand and cherish that sense of having a borderlands cultural experience ... not quite belonging to one [culture] or the other, but belonging really anywhere that you can make home," she said.

Though she was baptized in the Methodist church with Catholic godparents and was confirmed as an Episcopalian as a teenager, García's family was fairly nonreligious, and she was never particularly involved with an institutional church. Still, she "was always a deeply spiritual person whose felt sense of the presence of the Divine was in the natural world," she said.

She earned an undergraduate degree in English literature from Windham College in Putney, Vermont, where, at one point, she built a cabin she lived in. After graduation, García worked largely in consulting, communications or development.

García spent the early '80s as the director of media communications and, later, vice president at the nonpartisan organization Common Cause, working on issues related to government ethics, such as campaign finance reform and redistricting.

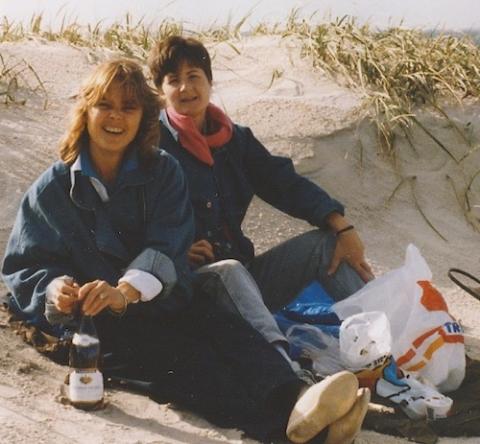

In 1985, Elise García, left, and her friend Derre Ferdon quit their jobs in Washington, D.C., to travel Europe for a year. Here they're in Denmark. (Provided photo)

One night, hanging out over glasses of wine with her housemate, friend and colleague Derre Ferdon, she had the idea for the two of them to quit their jobs in Washington, D.C., to travel around Europe. It was 1985, they were in their 30s, García knew enough languages, and they could stay with friends as they traveled through 16 countries, living off $25 a day for a year.

"I never would've done that without her encouragement," Ferdon said.

After their travels, García moved back to the capital "trying to figure out what to do with the rest of my life," she said. She reluctantly got back into consulting on fund developments and communications.

It was around then that García became close to Adrian Dominican Sr. Carol Coston. The friendship would ultimately change the trajectory of García's life.

García was consulting groups like Network, a Catholic social justice lobby, where Coston had been the founding director*. The more Coston invited García to events, the more García realized "the most interesting and dynamic people I was meeting were all Catholic sisters."

By 1992, García and Coston decided to move to South Texas with Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Nancy Sylvester to live together when García was recruited to be director of communications and development at St. Mary's University School of Law in San Antonio.

Those friendships and her first few years in Texas, she said, were "the beginning of my very mysterious call into religious life."

Advertisement

Several years before becoming a sister, Elise García got to know multiple Adrian Dominicans. At this picnic in 1991, García, left, is joined by, from left: Adrian Dominican Sr. Rosemary Ferguson, the congregation's former prioress one of García's two sponsors when she professed; Adrian Dominican Sr. Mary Philip Ryan; and Adrian Dominican Sr. Carol Coston, her other sponsor. (Provided photo)

García hosted Adrian Dominicans on her Texas property regularly, getting to know more sisters through Coston and their parties and mission meetings.

"We called her our favorite pagan baby," Coston said.

Though their bond over a sense of mission was always obvious, García said, "entering into a formal religious life — that certainly did take everyone by surprise, including myself."

It was Dec. 31, 1999, now a "mystical" night in her memory. She was in Adrian, Michigan, with Coston and other Adrian Dominican sisters, consulting the congregation as they envisioned the role of their retreat center, the Weber Center, as they entered the new millennium. When that retreat center held an inauguration for its new labyrinth that New Year's Eve, García was profoundly moved as she watched a procession of 100 people by the glow of a distant campfire.

She woke up the next day at the Weber Center and was surprised to hear a complete sentence: "The most radical thing a person can be in the 21st century is in religious life. So why aren't you?"

García shrugged off the questions, though they came back every morning in the ensuing days, even after she went back to Texas. Each time was more "unnerving" than the last.

A week later, she drafted a letter seeking admission to the Adrian Dominicans.

Ferdon remembered being stunned to find out her old friend was becoming a Catholic, let alone a nun. With García's mom and sisters, she remembered watching the newly confirmed García glow as she professed her vows while they all sat there, saying, "I can't believe it."

Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise García at the Santuario Sisterfarm around 2009 (Provided photo)

Although it was unanticipated, the decision also made sense to Ferdon, who said García was particularly taken by sisters' commitment to live like Jesus.

"Here is this wonderful, religious group of women that are actually doing what they talk about, living the kind of life she'd be comfortable with ... Her willingness to change and grow and see things in a different way — it's a gift."

Adrian Dominican Sr. Patricia Siemen said García's leadership is "so strong" precisely because she made that commitment later in life.

"There was something she saw in religious life [that] could actually make a difference in the world if we used our voice, that it was a way of leveraging moral authority from women," said Siemen, the congregation's prioress and head of its general council.

And just as García grew up between countries and identities, she now sees a parallel "borderlands" perspective in her religious life, she said: a baby boomer in age, but peer to the millennial sisters who also joined in the early 2000s.

Being of those two minds, she added, is an opportunity for her to serve as a bridge between the "Elizabeths and the Marys," or the elder and younger sisters: "both pregnant with new life, sharing a common ancestry, common values, but looking at very different futures," she said.

Santuario Sisterfarm: more than an eco-spirituality center

When García moved to Texas Hill Country in the '90s with Coston and Sylvester, they playfully called their 7-acre ranch "Sisterfarm."

But in 2002, after García returned from her religious formation, the plot of land turned into Santuario Sisterfarm, a nonprofit eco-spirituality center with García and Coston as the co-founders and co-directors. (Sylvester had moved back to Michigan by that time.)

The collaborative effort between Dominican sisters and Latinas from the borderlands was dedicated to cultivating cultural and biodiversity while teaching others how to live in "right relationship" with the Earth community, García said.

The guiding principle, Coston said, was to "give back to the Earth as much or more than you took from her." They taught others how the principles they used in their small acreage could also be applied to suburban backyards.

Adrian Dominican Sr. Carol Coston, center, gives a tour around the chicken coop at Santuario Sisterfarm around 2010. Coston and Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise García ran the nonprofit for about a decade, promoting a sustainable lifestyle and serving as a spiritual respite for local women. (Provided photo)

García and Coston were far ahead of their time in adopting and encouraging an ecologically sound lifestyle: rain catchment systems for their property's water usage, permaculture and organic gardening practices, "green" building with geothermal systems for electricity.

Janie Barrera, the founding vice president and treasurer of Santuario Sisterfarm, remembered García encouraging people to take off their shoes to feel the ground and take in its energy.

"What's cool about Elise is that she doesn't keep that energy inside. It becomes a spiral out of her to others, and it energizes," she said.

Inviting Latinas to be educated on permaculture while building a support system for them was the other component to Santuario Sisterfarm — a respite to nourish one's soul, friendships and land, said Siemen, who served on the board throughout the nonprofit's nine-year existence.

María Antonietta Berriozábal remembers the farm fondly as a place to meet and have deep conversations among those in Hispanas Unidas, the nonprofit she founded dedicated to the education, empowerment and advancement of minority women. (García served on the board.)

"I always tell Elise that she put me in touch with the cosmos," Berriozábal said. Others who spoke with Global Sisters Report said the same.

"The best advocate and teacher of caring for Mother Earth, that was Elise, a real leader," said Berriozábal, who was the founding president of the Santuario Sisterfarm board.

While running the nonprofit farm, García also became an editor and publisher of eight books for Sor Juana Press, as the farm encouraged women religious and Latinas to write a series of books.

In her time with Santuario Sisterfarm, García earned her master's degree in theology from the Oblate School of Theology in 2009. Two years later, she and Coston moved to Michigan when García became the director of communications and technology for her community. The two sold the Santuario Sisterfarm land to friends before their move.

And while people approaching 60 typically start thinking about retirement, said Barrera, a former Sister of the Word Incarnate and co-chair of Hispanas Unidas, "Elise [was] ready to take on a new challenge and a new deeper awareness of who she is and what she's been called to" — leadership in religious life.

Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise García, right, interviews Kichwa leader Ena Santi for Global Sisters Report at the COP21 climate summit in 2015 in Paris. (Provided photo)

Reinvention in the face of need

García's ability to "read, absorb and translate" complex concepts, Siemen said, was put on full display when she had to reinvent herself to address the Adrian Dominican congregation's needs — twice.

In her first five years living at the motherhouse, García oversaw the congregation's technological overhaul as communications director, educating herself for the multimillion-dollar investment and essentially learning "an entirely new language" in technology, Siemen said.

She learned another new language in the past five years — investment strategies — when she was on the advisory committee for the Dominicans' partnership with investment bank Morgan Stanley: To celebrate the fifth anniversary of Laudato Si', the 16 Dominican congregations contributed to the Climate Solutions Fund to address the effects of climate change on marginalized communities through a multimillion-dollar initiative.

"She is this incredible conscience," said Siemen, who has worked with her in leadership for four years. "She's brilliant with a heart of service to boot."

From left: Adrian Dominican Sr. Patricia Siemen, Amityville Dominican Sr. Margaret Mayce, and Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise García participate in the call for an international agreement addressing climate at the COP21 summit in 2015 in Paris. (Provided photo)

In 2016, García was elected general councilor of the Adrian Dominicans. She served on the board of LCWR for two years before joining the triumvirate presidency for 2019-2020 as president-elect with Holy Cross Sr. Sharlet Wagner as past-president and Helmlinger as president. All also work closely with St. Joseph of Philadelphia Sr. Carol Zinn, the conference's executive director.

The collaborative nature of leadership in religious life, García said, plays to her strengths.

"That team approach — having those different perspectives woven together, learning from one another — has just been a wonderful gift, a deepening of my regard for the capacity of these extraordinary women and their dedication to the larger mission of religious life in the United States and beyond."

Since entering into congregational leadership, García said her community has been engaged with the wider Dominican Sisters Conference. And since she entered religious life, she said, they've been recognizing "painfully" yet "expectantly" what the future holds for ever-adapting religious life.

"We are at a profound moment of change in terms of church and society, religious life, globally," she said. "There is evidence everywhere you turn."

García sees parallels between the diminishment of members within religious life and the diminishment of the Earth's resources. She said both situations call people to a radically different way of being.

In recent years, she said, those shifts have inspired a more contemplative religious life as the vocation has attracted more diverse sisters.

"So, we have the gift of diversity in our circle now in ways that we didn't when we had the very large numbers of the past," she said.

The changes taking place in religious life, therefore, are "positioning us right now to really help participate in the profound transformation that is needed" in society today, she said. Ideally, she added, this should also lend to a more sustainable life for generations to come.

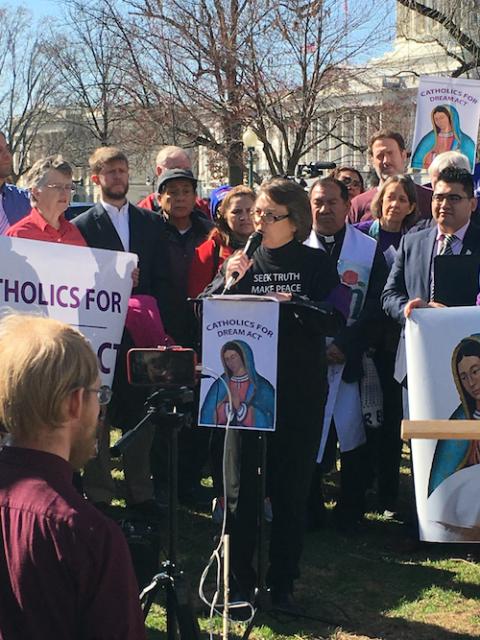

Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise García speaks at a press conference at Capitol Hill as part of the July 2019 Catholic Day of Action for Immigrant Children. She was later arrested. (Provided photo)

Leadership in an uncertain time

García's presidency begins in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, which as of Aug. 11 has killed more than 160,000 people in the U.S. while shuttering businesses and devastating the economy, and nationwide protests against systemic racism and police brutality.

In the National Catholic Reporter's EarthBeat, she wrote about the profound fault lines the pandemic has exposed in its disproportionate impact on people of color.

"We can't return to normal because normal was the problem," she wrote.

She told GSR she sees a link between the pandemic and the environment, attributing the fact that viruses come from animals to humans "because of our incursions into areas of wildlife where humans should not be treading."

Because sisters have been encouraged to shelter in place as a precaution against the pandemic, now has been a time of deepening prayer, she said, equating quarantine with the metaphor of a cocoon being an opportunity of transformation.

"It's my hope that we in LCWR can play a part in that" transformation, she said, both within themselves as individuals and leaders and within their communities and the ones they serve.

As countrywide protests for the Black Lives Matter movement have put the issue of police brutality against Black people at the forefront of national discourse following the killing of George Floyd, LCWR leadership met with the National Black Sisters' Conference earlier this summer to discern how religious leadership should respond to systemic racism and white privilege.

What emerged was a five-year commitment — "A Spirit Call within a Call" — that aims to address racism "as the critical social and moral issue of our time," García said. "As I assume the role of president of LCWR, I want to do all I can to help us embark on this transformative journey of reckoning with the soul sickness of racism."

Barrera said the timing of García's ascent into national leadership is not coincidental, but "providential": García has her eye on "the North Star."

Berriozábal said LCWR, like other national and international organizations, needs leaders who can understand what the people are marching for, scared of, and celebrating. She said she thinks García can do all of that.

"Long before now, she's been prepared," she said.

As García moves from president-elect to president, she's most excited to see what it is that women religious can "draw from our religious imaginations."

"I do believe that the wisdom is not in any one of us. It's in all of us coming together across cultures, across race lines, across all of our differences," she said. "That is the future that is beckoning us, and I'm excited about moving in that direction."

Knowing that the Adrian Dominicans were quarantined on campus, Black Lives Matter marchers routed the June 14, 2020, march to come by the motherhouse so sisters could participate, García said. The general council, from left: Sr. Frances Nadolny, Sr. Elise García, Sr. Patricia Harvat, Sr. Mary Margaret Pachucki and Sr. Patricia Siemen. (Provided photo)

*An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect position for Coston.

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Her email address is ssalgado@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @soli_salgado.]