As revelations of the scope of sexual abuse and infighting among church leadership continue to shake the Catholic world, women religious say they can be the key to structural changes in the church as well as the healing the church and churchgoers alike need.

Sisters say solutions include giving women religious and laypeople authority in sexual abuse cases so the decision-makers are outside the power structure that in the past has protected abusers instead of victims; putting women religious in positions of authority within the church to end a climate of clericalism; and including more women religious in the vocation process for priests.

Holy Cross Sr. Sharlet Wagner, president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, said first and foremost, sisters need to focus on healing.

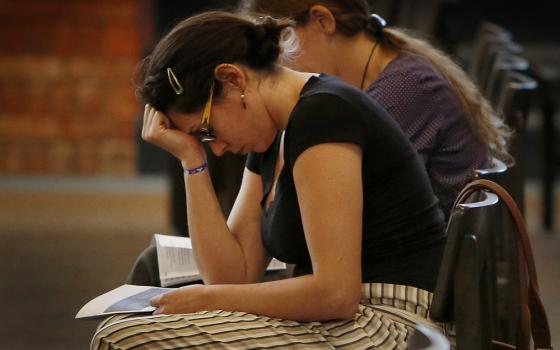

"Sisters can respond by listening compassionately to victims and to all Catholics who are rightfully outraged over the abuse that has occurred," she said. "People are angry. They feel betrayed, and they need safe venues to express their anger and their sense of betrayal. We all need to hear that."

Sr. Kathleen Bryant of the Religious Sisters of Charity of Culver City, California, said the crisis is particularly painful because in her more than 20 years as a vocation director in the Los Angeles Archdiocese, she saw firsthand the need for more women and members of the laity in key leadership positions.

"What's making me raging is that we're all in the same stuck place: The decision-making and authority is with these males," Bryant said.

Sr. Mary Ann Zollman, a Sister of the Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, said the clericalism that enabled the abuse and encouraged its cover-up prevents the formation of a genuine community within the church.

"Clericalism is actually one of the reasons many women religious don't want to be ordained," Zollman said. "They don't want to be seen as becoming part of a clerical class or caste."

She said many women religious are spiritual directors or run parishes as parish administrators but are seen "almost as second-class citizens" compared to priests.

Ending clericalism will also allow the ongoing, open and honest conversation that healing requires, Zollman said.

Ordaining women would not fix what is ailing the church unless the culture of clericalism is addressed, said Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell, executive director of Network, a Catholic lobby for social justice.

"Women can be as easily seduced into power as men," Campbell said.

True healing can only come with change, multiple sisters said.

"The church needs to examine not only what happened, but why it happened. The church needs to go deeper and look at the root causes of this," Wagner said. "Why was there so much sexual abuse, and what led to the cover-ups? Perhaps what the church may need is a commission to bring everything to light and go deeper and examine the root causes and then to make changes."

Simply studying the issue is not enough, she said, and it cannot be done by clergy alone.

"There are a variety of root causes. I don't think there is any one cause," Wagner said. "I wouldn't want to speculate on what all those causes are, but I believe we need a group made up of laity, religious, clergy, people with expertise to really examine this."

Wagner said women religious should be a part of any commission the church sets up.

"Women religious have a certain credibility that they could bring to the commission," she said. "Women religious are intimately involved in the church, have a deep love of the church, have committed our lives to the church, but we are not part of the hierarchal institution. I believe women hear stories of abuse in a different way, so the commission certainly needs women and needs women religious."

It is unclear what, if any, authority such a commission would have, another example of how change must include examining the existing power structure of the church, said St. Joseph Sr. Amy Hereford, a civil attorney and a canon lawyer.

"Currently, the local bishop is the chief legislator, chief judge and the chief executive of the diocese," Hereford said. "Expanding participation in this power structure will be critical for any change."

A power structure that protected abusers and their enablers is fundamental to the lack of trust people, especially victims, have in the church, said Tim Lennon, president of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, which includes survivors of abuse by priests (including sisters) and survivors of abuse by sisters.

"We've heard the pope, we've heard the thoughts and prayers," Lennon said, "but none of that makes a child safer."

Lennon said he is unsure what role, if any, sisters could play in changing policies to prevent abuse.

"We have no faith or trust in the church protecting children or telling the truth. We want the church out of the process entirely. We want civil society to investigate," Lennon said. "We are calling on the U.S. Department of Justice for a third time to conduct a national investigation, and we're calling on all of our network to write to their attorneys general to demand, implore or beg to have a grand jury investigation in their state."

Wagner said she understands why people do not trust the church to examine and reform itself — and that may extend to distrust of women religious, some of whom have been accused of abuse themselves: A four-year investigation from BuzzFeed published Aug. 27 detailed severe abuse at sister-run orphanages.

"I'm aware that there have been cases of abuse by sisters, to our great shame and our great sorrow," Wagner said. "I believe it's far from the same scale [as abuse by clergy], but even one abused is too many. ... People are rightfully angry about the greater desire to protect the institution than to protect the children. That's part of the whole thing that needs to be uncovered and addressed."

Wagner said LCWR provides resources and services for its member congregations but has no authority over them or within the church, limiting its ability to respond to the crisis. But LCWR had an abuse victim address its 2004 annual assembly, and leadership met with SNAP representatives later that year to develop workshops on responding to sexual abuse by women religious, Wagner wrote in an email to Global Sisters Report. The organization also examined policies that congregations had in place and developed resources for improving them and compiled a bibliography of resources on sexuality, boundaries and abuse for all members, she wrote. LCWR repeated the examination and updated its member policies in 2008.

Church structure 'must be examined'

Having more women involved in the vocation process could help prevent abuse from occurring in the first place, Bryant said.

"It was good to have a woman" in the Los Angeles Archdiocese's vocations office, Bryant said. "Sometimes, I picked up things in [potential seminarians] that other priests didn't pick up."

Dioceses tend to appoint young priests as vocation directors, but they don't have sufficient experience, and the bureaucracy and lack of coordination frustrated her. Her office would turn down certain men for the seminary, but she would travel to another diocese and "see a vocation poster, and that guy would be on it, or he'd be ordained in another country. The church does not work together well on this."

Those within the church must also have the courage to examine what has happened, said Irish Sr. Jean Quinn, executive director of UNANIMA International, a United Nations-based coalition of Catholic congregations focused on concerns of women, children, migrants and the environment.

"It's really important to offer compassion and apology for what has taken place," Quinn said.

The recent revelations in the United States have been "shocking," she said, but it is not enough to be shocked. "I want to go further: The problem has to be brought into the light, and issues of church structure and policies must be examined."

Quinn, who was provincial for the Daughters of Wisdom for England, Ireland and Scotland from 2005 to 2015, said one concrete thing that could be done for Catholic dioceses is to establish advisory "safeguard panels." Such panels could ensure policies are instituted to protect children and vulnerable adults who are put under care of the church, be it in schools, hospitals or other health care institutions.

Hereford said changing the way things are will be difficult, at best. Canon law has no provision that allows for giving laypeople power over sexual abuse investigations. A National Review Board made up of laypeople advises the U.S. bishops on policy but does not have decision-making authority.

Some canon lawyers are calling for a national commission tasked with receiving and evaluating allegations then passing its findings to the Vatican for final decision-making. The U.S. bishops could also ask the Vatican to grant the group authority to judge accused bishops on its own.

The Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has authorized diocesan tribunals in the United States and Canada on a case-by-case basis to handle proceedings normally reserved for its consideration; that arrangement could be made permanent, said Oblate Fr. Francis Morrisey, a former president of the Canadian Canon Law Society who has advised numerous Vatican offices and local bishops' conferences.

Canon law could also be changed, but that is a complicated process, Hereford said.

To change canon law, "You would have to have a theology that would support laypeople having power," she said. "In the early church, the councils were called by emperors, not bishops, so it's not unheard of."

Address pain, enter into it

The pain victims endure when abused by priests or religious is amplified by the perpetrators' role in the church, said Sr. Esther Fangman, prioress of Benedictine Sisters of Mount St. Scholastica in Atchison, Kansas, and a psychologist who specialized in counseling trauma victims.

"It is like they are committing an abortion of the soul of the victim. Sexual abuse may be an 'incident' for the perpetrator, but for victims, they spend their entire life trying to put together trust: trust of God, trust of others, trust of themselves," said Fangman, whose clients include those who have been sexually abused by priests and religious brothers.

Because of the religious role of perpetrators, "God also becomes part of their question. ... 'Not only [do] I feel shameful and worthless but God sees me that way, too.' "

The pain extends beyond victims to affect the larger church, she said.

" 'How do I stay Catholic?' People have asked me that in the past few weeks," Fangman said. "There is a crisis. They are really pained by what they are hearing. I tell them it is a piece of our brokenness that must be dealt with."

Wagner said being a sister in this moment is "difficult."

"For women religious, we love the church deeply and have dedicated our lives to this," Wagner said. "Many women religious have dedicated their lives to serving children as well, and so to see that some of the ministers of the church have committed such horrific acts against children and that some of the leadership has enabled that by covering it up is something that we find very painful."

But that pain must be addressed, she said.

"The temptation can be to run from the pain. That's what we tend to do as a society, to cover it up, to find a quick solution and move on," Wagner said. "I think what we have to do is enter into that pain and keep going into it and come out the other side and not find a quick answer, this one solution and move on."

Bryant said there is a lot of anger toward the church, which is not necessarily a bad thing.

"We should be angry, and anger is not a sin. I am personally in a rage about this," Bryant said. "These are not all old cases. This clericalism that Pope Francis has been challenging feeds on secrecy and cover-ups and anything that protects the image and reputation of the church above the person [harmed]."

Anger can be a catalyst for change, she said: "The quote that keeps me going these days is from St. Augustine: 'Hope has two beautiful daughters. Their names are Anger and Courage: anger at the way things are, and courage to see that they do not remain the way they are.' "

Amityville Dominican Sr. Ave Clark, a survivor of sexual abuse and a counselor for survivors at the Heart to Heart Ministry in Bayside, New York, said the church's approach of temporary fixes will no longer suffice.

"You have to look at the whole church," Clark said. "I think it's going to be a humbling experience — far more humbling than they ever thought."

The lack of trust in the church, she said, is a situation of its own making.

"The worst thing that could have been is the cover-up, where they thought more about the church than human beings," Clark said. "We can't keep saying words. We have to be transparent. ... They have to listen to the people. They have to let down their guards."

The first step, she said, is for the church to honestly admit its failure.

"A survivor can understand your weakness," Clark said. "Come forward. At least be honest."

Church leaders also have to be honest in admitting they need outside oversight, she said.

The bishops "can't do this on their own, and this thing of doing everything behind closed doors is not good," Clark said.

Wagner said a transparent process will be painful, she said, but there is no shortage of pain already.

"I have heard so many priests in homilies [describing] the great pain that they are in. I wouldn't want to compare that pain to that of the victims, [but] in some instances, all priests and bishops are being tarred with the same brush," Wagner said. "I'm not sure how much the public is aware that the vast majority of the priests are faith-filled and faithful ministers of the Gospel who are doing their best and are suffering great pain from what is going on with the church that they serve and they love — and women religious are sharing in that pain, as well."

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook. GSR editor Gail DeGeorge and GSR international correspondent Chris Herlinger contributed to this story.]