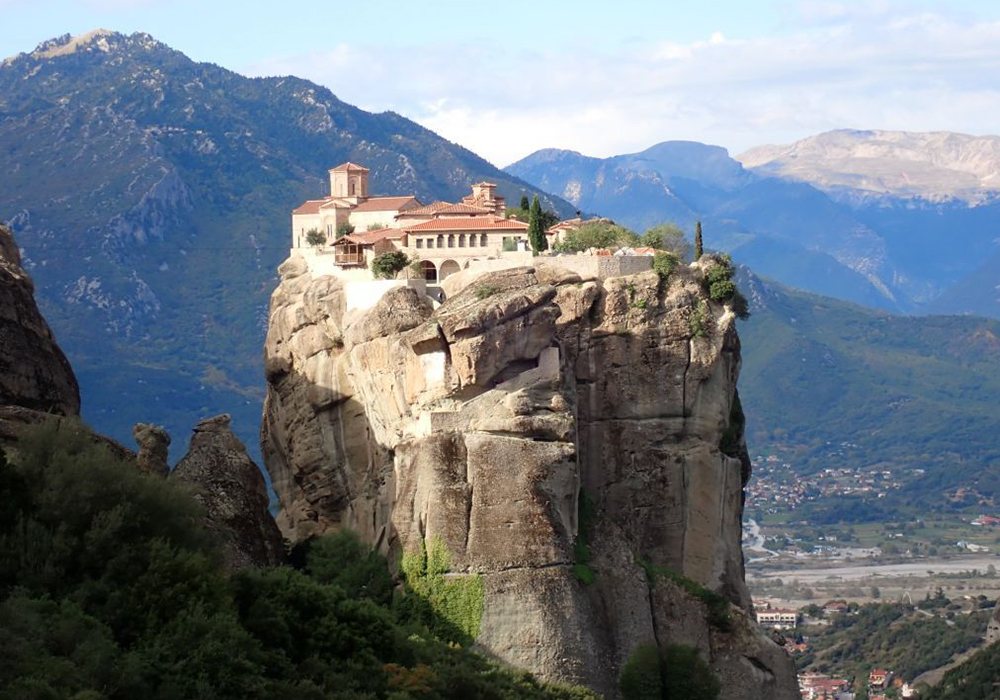

Meteora is the second-most popular tourist destination in mainland Greece, drawing some 2.5 million visitors a year, second only to the Acropolis in Athens. The region was popularized in the James Bond movie "For Your Eyes Only." (GSR photo/Gail DeGeorge)

Editor's note: Global Sisters Report Editor Emerita Gail DeGeorge recently participated in a biblical study tour to Greece and Turkey with Catholic Theological Union.

Through my work with Global Sisters Report, I've been privileged to interview sisters in a wide variety of places for an amazing array of topics. In Hiroshima, I spoke with sisters who remembered the 1945 atomic bombing. I witnessed how sisters in Thailand are helping women escape the country's sex tourism trade. And in Myanmar — before the military regime reasserted control — I learned how sisters were using sustainable farming to support a girls orphanage. These are just a few examples.

But the most unique — and breathtaking — venue for an interview with a sister was with the recent biblical study trip to Greece and Turkey with the Catholic Theological Union. The day's itinerary simply called for a visit to "Meteora and the Monasteries 'suspended in the air.' " The small black and white photo in the program showed a collection of buildings perched precariously at the top of a cliff.

GSR Editor Emerita Gail DeGeorge interviews a sister from the monastery. (Courtesy of Gail DeGeorge)

Yet that did not begin to convey the amazing wonder of the Holy Meteora, a group of six still-active monasteries out of 24 original refuges built for prayer and pilgrims atop a collection of giant stone mountain cliffs, about 135 miles (217 kilometers) from Thessaloniki, Greece's second largest city.

The origins of these holy places — registered as a Unesco World Heritage site — are thought to date to the 11th century when monks and hermits sought solitude and peace amid the cavities within the cliffs. In the 14th century, monks found the region a shelter from Turkish raids. Over time, they built more than 20 monasteries cradled improbably amid the towering cliffs, stunning examples of architectural ingenuity, human perseverance and spiritual inspiration. The six that remain active house breathtaking Byzantine paintings, mosaics, carvings and ornate candelabras, crosses and sacred objects.

The St. Stephen monastery is now a convent in which 31 Orthodox nuns live. (GSR photo/Gail DeGeorge)

As the bus wound its way amid the steep mountain roads, we collectively gasped as the vistas opened to reveal countless cliff tops. Even though we had gotten an early start, to my surprise, we were soon joined by more than a dozen other tour buses also visiting the monasteries. I should have expected this: some 2.5 million visitors go to Meteora, making it the second most popular tourist destination in mainland Greece, topped only by the Acropolis in Athens. (There was something ironic to me about so many people visiting holy sites in which the monks and nuns seek a life of solitude and prayer.)

Advertisement

Our first stop was the Holy Monastery of St. Stephen, a convent since 1961 for a congregation of Orthodox nuns, now numbering 31 members. I had asked our Greek guide, Ioana Kaitatzi, the night before if I could interview one of the sisters. She was not encouraging. Generally, she said, the sisters do not speak to any of the hordes of pilgrims and tourists who visit the monastery. They live a simple, monastic life, away from contact with the world, she explained, but they were also Greek Orthodox nuns and therefore might not want to appear in a publication focused primarily on sisters and nuns from the Roman Catholic Church. Still, I gave her my business card and hoped for the best.

Partway through our tour of the monastery, with its incredibly detailed and intricate paintings and mosaics, I got my request. Sister Gregoria said she would talk with me briefly.

In English, she explained the focus of the monastery and the rhythm of the sisters' daily life. "The center of our life is prayer," she said, while other religious communities center on helping people with material needs and social issues. While the monastery does help people financially all over the world, "our main part is prayer, because through prayer, God is the one who acts," she said. "Through human efforts, we can help 100 persons or a million, I don't know. But God can help everyone."

More than 100 miles outside the city of Thessaloniki, in northwestern Greece, is the rock formation Meteora, which translates to "suspended in midair." (GSR photo/Gail DeGeorge)

As our Creator, she said, God knows best how to help us. All tasks, even the most menial, are offered to God. "Even if you clean the yard, you offer this to God," said the sister who, like many of her fellow sisters, entered the convent right after university studies.

Daily life begins before 5 a.m., when sisters wake and make personal prayers. At 5 a.m. they begin their common prayer and services. At 8 or 8:30 they pray the Divine Liturgy or gather for Mass offered by a priest.

A daily limit of 20,000 visitors for the region is now set for the St. Stephen monastery. (GSR photo/Gail DeGeorge)

The monastery opens to visitors at 9 a.m. "We have a special place here with visitors from all over the world," she said. "We keep the tradition, the spiritual tradition — we want to keep and not destroy something." Sisters have various tasks: one is responsible for the museum, another for the church or to clean the yard. Other sisters have tasks inside such as sewing habits worn by the sisters, making handiware sold in the shop, painting icons or decorating manuscripts, or writing books about prayer.

Midday, the monastery is closed to visitors and the sisters gather for a common lunch together. Someone reads a spiritual text, often about the life of a saint. Then the monastery reopens to visitors for the afternoon, and tasks are divided again among the sisters.

At 6 p.m. there is vespers until 7:30 or 8 p.m. Then there is time for personal prayer, reading or studying. "This is part of our personal rule, because we have a rule to pray personally. There is a certain hour we have to go to bed because the next day, we have to wake up early."

A system of nets, baskets and pulleys are used to bring supplies to the monasteries. (GSR photo/Gail DeGeorge)

This is the structure of their external life, she said, and the internal life is "prayer for all the world."

The world certainly needs their prayers, I thought, especially then as a hurricane threatened family and friends in Florida, with wars and conflicts engulfing so many regions, a bitterly contentious election in the U.S., and the litany of those battling serious health conditions who I keep in mind and in my prayers.

It was hard to break away, to end our visit and board the bus, and then head to Athens. There was such a peacefulness in the remoteness of the sisters' world, in cherishing the amazing beauty of God's creation — and the art made by humans to worship God — and in walking along ancient footpaths in monasteries so high they seemed to touch the sky.