Sr. Rosemarie González, a School Sister of Notre Dame (GSR photo / Soli Salgado)

(GSR logo / Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Editor's note: More than 1.6 billion people worldwide live in substandard housing. Of those, at least 150 million have no home at all. In this special series, A Place to Call Home, Global Sisters Report is focusing on women religious helping people who are homeless or lack adequate shelter. Over the next few months, we will examine how homelessness and a lack of affordable housing affect teens and young adults, families, migrants, the elderly and those displaced by natural disasters and climate change in stories from Kenya, India, Vietnam, Ireland, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, the United States and elsewhere.

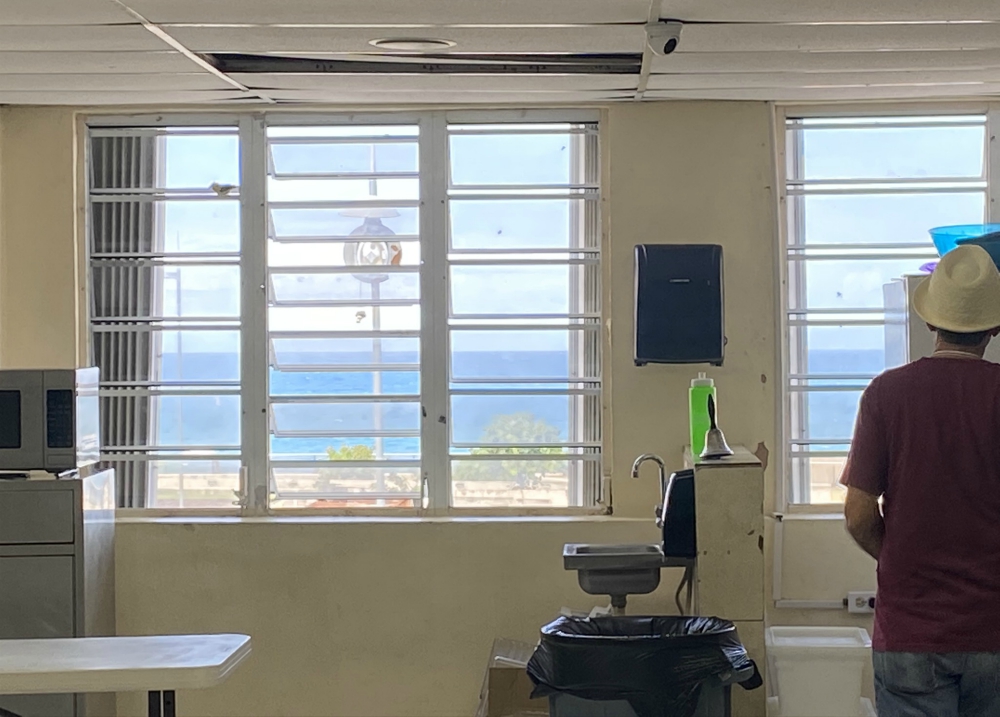

The three-story Home of the Good Shepherd for recovering addicts overlooks the ocean in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and for many of its residents, that view is the "first time they've seen the ocean," said Sr. Rosemarie González, a School Sister of Notre Dame. They've been around the ocean their whole lives, but they had been too high to appreciate it.

In 1993, González founded the 50-bed recovery transitional home, where homeless men and women with a history of drug abuse are welcome to stay so long as their recovery journey focuses on drug abstinence.

"If you go to other places, you'll see that the detox is separated; they're isolated," González said. "And I find that to be the worst thing you could do to somebody who's going through anxiety. Here, you don't know who's in detox and who's not," she said, adding that those in detox have certain privileges — such as the freedom to eat, bathe or watch TV whenever they want — to help ease their anxiety or pain.

El Hogar del Buen Pastor — Home of the Good Shepherd — is located in the Puerta de Tierra neighborhood of San Juan, Puerto Rico. (GSR photo / Soli Salgado)

González considers community living at the heart of the rehabilitation.

"Many of them have been using substances or alcohol since they were 9 or 10, so they've missed out on regular, everyday growth and experiences," González said. At the Home of the Good Shepherd, "they have up to two years to try to make that leap and get to their age."

Residents participate in job training depending on their interests, working around the shelter throughout their stay in maintenance or cooking, for example. After two years, some can move on to the center's expansion program, where 18 individuals move to a different section of the building and take on jobs with employers, easing into having more freedoms, buying their own food and no longer having a curfew.

The social skills they learn along the way, however, may be the most important takeaway from their job training in the home.

"They need to learn how to deal with anger, how to deal with working with somebody else because they've been in the street for many years and have lost those skills," González said. And though most of them are "very intelligent," their ability to work with others has been stunted through addiction and life on the street.

"As homeless addicts, they've been very individualized. They were never able to develop."

GSR: You say they start addictions young. What accelerates drug use? Are drugs easy to come across in San Juan?

González: In the States, we understand that the majority of the homeless, from what we see in statistics, are people who have lost their jobs or have mental illness. I think the addiction problem is growing in the States, but for us, the addiction problem has always been the top 80% of the people who are homeless. It's not really people who just aren't working or lost their job. So, there's a need for helping them to overcome the addiction, but also everything that they have lost because of the addiction.

Advertisement

Here [in Puerto Rico], we are people who celebrate a lot. Whatever party there is, it has to be with alcohol, so that and drugs are very easy to come by. And now with pills — not only opioids, but other medicines, too — they know what they have to tell the doctor if they want to get a prescription.

What's a typical profile of someone who comes to your shelter?

Usually, they've been abused by a family member. Violence, too, especially by parents influenced by alcohol. Traumatic experiences. Mainly, they've used drugs, with peer pressure in one sense, but mostly to run away from facing problems. They're not necessarily people who come from poor homes. It's a mixture. Many of them, because they've started at an early age, don't know how to face the difficulties in life, so they use as an escape.

When I began, the biggest problem was alcoholism. Then it was the other substances — heroin, cocaine, you name it — and now, it's more synthetics. For the first time in 27 years, we had overdoses. We had six overdoses; one died. The first one, we didn't see coming at all, and it's not just that. It comes quick, in five or 10 minutes, and if you don't move fast, the person dies. That's made it more difficult in these last years, the different mixed substances that they're using.

How do they find you?

Sometimes the police bring them. Sometimes they come on their own or because they've heard from others who have stayed here. Sometimes their families get them from the street and convince them to come. Sometimes they get out of prison and they don't have anywhere to go, so they come here. But they have to be here voluntarily.

The Home of the Good Shepherd in San Juan, Puerto Rico, has 50 beds, with one bedroom for women and three bedrooms for men. (GSR photo / Soli Salgado)

Walk me through the differences in setup for the 50 who stay in the shelter and the 18 who are in the program long-term.

We have room for 42 men and eight women. (There's just more men on the streets.) Each person takes the process differently, as far as length of time. When we feel and they feel that they're ready to find a job with an employer — which is usually after a year — then we have a section of the building where we move them. There, they have many more liberties as far as their schedule is concerned so that they can look for a job and accept jobs that are maybe at night.

And then we have vouchers for 13 apartments for those who finish here, who have a job and are ready for their own living quarters if there's space. They have that choice.

We had that option for women, also, but the women were not asking us for help. Many of the women take to prostitution instead of asking us for help.

What are some of the biggest challenges you witness them go through when they leave the program?

The biggest difficulty is that they don't have 50 people around them. They're alone in their apartment. That's another reason for what we call the expansion, because there's less people there, they buy their own food with food stamps, and they start to become independent so that when they get out, it isn't such a shock.

The lobby of the Home of the Good Shepherd in San Juan, Puerto Rico, has a gallery wall with framed articles featuring the home, as well as group photos of residents. Here, Sr. Rosemarie González shares memories of a group of people, some of whom are now deceased, who started a business together. (GSR photo / Soli Salgado)

Tell me about a specific case that stands out in your memory.

A woman came about two years after we had begun the center. She was studying nursing, but she had been an addict for quite some time and had also fallen in to prostitution, so when she came here, it wasn't easy. Many of them come with attitudes that have to be dealt with, a lot of anger, fear. And she came with a lot of anger.

She had some relapses — almost all of them have relapses — but she kept working, and after six months, she went back to studying in addition to all the AA meetings we had here. She graduated from college as a nurse, and we employed her here. Then the municipality hired her for their public clinics, and now she's celebrating her 25th anniversary being clean. She's someone who's gone through the whole process from beginning to end.

You sound so patient as you talk about these cases. Did you struggle in reserving judgment in the beginning?

In the beginning, it was really hard. I didn't have any studies in addiction or homelessness, and at the time, there wasn't much help for homeless addiction here in Puerto Rico.

Our sisters have a school here, and I began by giving out lunch. Whatever was left in the cafeteria, I would give to addicts who at that time were alcoholics. I did that for two years, and they were fine, but they were still in the street. They were happy because they had food, but I didn't see any progress.

The mosaic on the outside wall of the Home of the Good Shepherd in San Juan, Puerto Rico, was done by a former resident, who has since died. (GSR photo / Soli Salgado)

What happened was, I met up with a little boy, and he asked me if I was of God, and I said yes. We had a conversation, and he asked me, if I found somebody thrown on the street, would I take him to my home and take care of him? And I swallowed. But it was at that moment that I understood, because I was looking to see what God wanted me to do. It struck me when he asked if I would take them into my home. I'd have to get a place and live there, too, so that's what I did.

I didn't have studies or formation for that. I had community living behind me, so for me, that was basic to the whole program. When I began, people would be coming and staying a while, and then they'd have a relapse and would leave. It was really hard for me because I really didn't understand what was happening. I didn't understand the difficulties they had. And getting to know them and seeing them leave, and then seeing them around here again in bad condition and really suffering — that was hard for me.

This was something different for my congregation. We're usually in schools. And they knew I would need some backup, some help, so they asked me to go to a psychiatrist friend of theirs. And being able to talk with him about my fears, my sadness, my disappointment with so many of them beginning and not finishing — we have people come back four, five, eight attempts. It's not easy for them. Being able to share that helped me keep a sense of balance and not letting it get to me.

I started seeing that it wasn't something I wasn't doing and that it was to be expected — I had to learn how to deal with that. In one sense, that has always kept me looking to see what else can be done or how better things can be done.

And I just think, "God, let me see that they're people like everybody else. They have their faults and their limitations, and they have their gifts." And living here with them helped me be more compassionate.

Sr. Rosemarie González said many residents tell her that living in the Home of the Good Shepherd in San Juan, Puerto Rico, is the first time they've truly seen the ocean, as they've previously have been too high to appreciate it. (GSR photo / Soli Salgado)

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Her email address is [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @soli_salgado.]