A choir of young women in Good Shepherd ministries in Sri Lanka open the July 30 webinar on the rights of girls in Asia and the Pacific. (GSR screenshot)

I will never forget the first time I landed at the airport in Bangkok in 2001. Walking through the airport to the baggage claim, it seemed everywhere I looked, old men were sitting about, accompanied by young girls. I had heard about the sexual exploitation of young women in Thailand but had never anticipated it to be so graphically in your face.

Later on that trip, Sr. Mary Walter Santer, an Ursuline sister from the United States who lived most of her life in Thailand, took me to a street in Bangkok lined with storefronts where young women were being "displayed" and, later, to Fountain of Life Women's Center in Pattaya, where Good Shepherd Sisters were offering training for women who desired other options for employment.

Having again seen the work of the Good Shepherd Sisters in Pattaya in 2017, I was excited to attend a virtual launch July 30 of a new study about the sisters' work with girls in Asia and the Pacific, "A Good Shepherd Practitioner Understanding of Girls Rights' Attainment."

Focus on girls is not a surprise because it has been the sisters' focus since the 1820s, when they were founded. What makes the study unique is that the data comes from on-the-ground practitioners working in Good Shepherd social service and education ministries.

These practitioners live with the realities of what girls experience every day in 19 countries of Asia and the Pacific: India, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Macau, Myanmar, Nepal, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand and Pakistan.

The study focuses on the issues experienced by girls 18 and under and aligns with current global dialogue on those issues, their root causes and some of the best practices in addressing them. It gives voice to what girls themselves want to tell the global community about their lives and their desire to be involved in bringing about solutions.

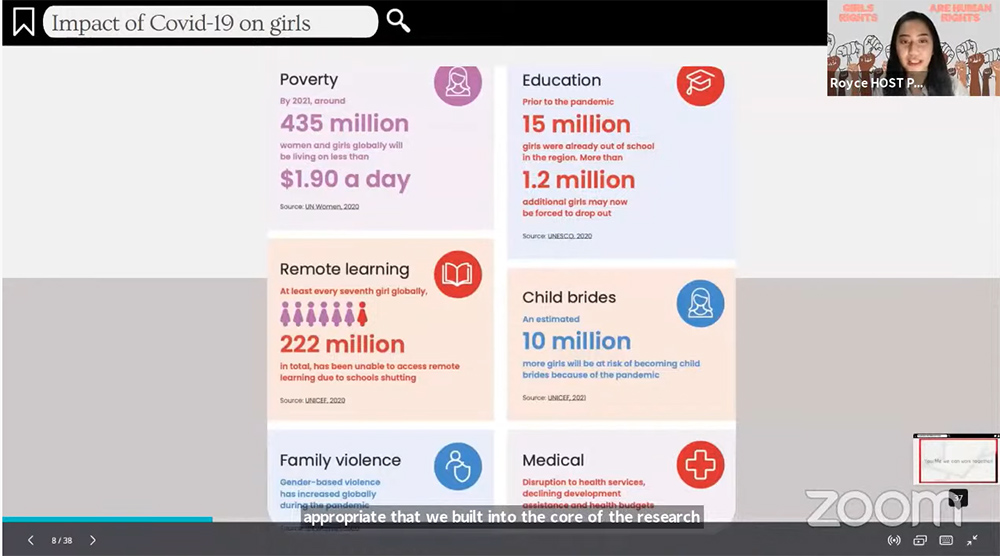

One of the four hosts of the July 30 webinar on the rights of girls in Asia and the Pacific presents statistics on how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected girls. (GSR screenshot)

Making such a resource available will, no doubt, increase the power of girls' voices worldwide and hopefully lead to increased collaboration of those committed to keeping girls at the forefront of human rights discussions not only throughout Asia and the Pacific, but worldwide.

What impressed me immensely about the July 30 webinar was how the launch put into practice what the practitioners have discovered together: Girls can speak for themselves.

The four hosts modeling collaboration, all under the age of 18, were from India and the Philippines. Their enthusiasm and articulate introduction of each part of the program was inspiring and made watching it fun.

The launch began with a beautiful song composed and performed by young women in Good Shepherd ministries in Sri Lanka. Then, throughout the program, videos gave voice to the girls living injustices in the Philippines, Myanmar and India.

The two authors of the research, Lily Gardener of Australia and Theresa Symons of Malaysia, strongly believed that after working for many years with young women in the region, it was time for a study outlining the human rights injustices alive in Asia and the Pacific in the combined systems of culture, religion, education and social services.

Forty practitioners in 15 countries where Good Shepherd Sisters work with girls answered the online survey, and from this group, 11 were selected for deeper discussions about their work within a rights-based context.

Putting girls first and really hearing their voices became important themes. So often, adults think they know what girls need, but the study revealed something different. Girls themselves know what they need. They want their voices heard, and they want opportunities to use their power to change things.

The interviews and group conversations revealed similar gender and social norms in each of the diverse societies in the 19 countries that keep girls from developing to their full potential. Gender and social norms systemically perpetuate attitudes and behaviors where girls are considered inferior to boys, incompetent and unworthy of basic human rights.

Research authors Theresa Symons, left, from Malaysia, and Lily Gardener from Australia speak at the July webinar on the rights of girls in Asia and the Pacific. (GSR screenshot)

Four major gaps were identified that prevent girls from attaining their full human rights. As I read these and listened to the stories, I recalled the girls I encountered when I lived in Zambia and those I met in my former work at the Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters. (Editor's note: The Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters is a separate organization from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, which funds Global Sisters Report.)

- The first gap is lack of access to justice, one of the greatest barriers to girls' development. Countries may have laws and policies about rights that protect girls on their books, but they are not implemented either because of lack of will or the influence of culture or religion. Girls themselves noted that their unique concerns are hidden in general categories of women, children, adolescents or youth, and this invisibility offers loopholes that prevent even reporting rights abuses of any kind. A 2020 report from UN Women confirmed that less than 40% of women who experience violence seek help, because they do not expect to be heard.

- The second gap is access to gender equality. Girls reported being left out of equal access to education, payment for services, health care and freedom of choice because of their gender, to name a few, and this combined with being of the "wrong" race or class or being a migrant leads to even less consideration. Many girls have no choice about marriage and become mothers without consent, either through gender-based violence or parent-arranged marriages for economic reasons. The girls know that becoming a mother without any education or skills continues a cycle of poor health and underdevelopment for themselves and their children.

- The third gap is access to quality education. Girls might attend primary school, but attending secondary school or beyond is often only a dream. Opportunity for primary school does not ensure success: The Good Shepherd study reports that one out of every five girls in the region is unable to read or understand simple texts by the age of 10. Heavy and tiring work at home along with poor nutrition and domestic trauma deters both motivation and facility to learn.

- The fourth gap is access to health and well-being. Geography, class or ethnicity, availability or affordability are elements that can inhibit access to good health and well-being besides culture and religion. Girls living in remote areas can experience isolation or a dearth of personal support and safety if they have no one to confide in. Girls reported the burdens of being responsible for family economic issues and frequently bearing the brunt of domestic violence, whether physical or psychological. If girls are unable to attend school with peers and teachers, access to personal support is usually missing.

Advertisement

Although there are solutions to overcoming these gaps, it will take a lot of work, particularly in places where traditional practices and attitudes are entrenched.

Sexual and domestic violence are prevalent in Asia and the Pacific, which, according to a 2019 report from the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, has the largest number in the world of women and girls intentionally killed by intimate partners or family members. Laws, policies and social norms rarely protect girls and women because supporting the rights of men and boys is a priority. Law enforcement, judges and protective service providers all need training in human rights to end this pandemic.

Making space for leadership and participation in decision-making for girls is another solution. However, again, entrenched economic, social, cultural stereotyped gender roles make it difficult unless boys and men join in this solution and realize that these stereotypes hurt them as well as the girls.

The girls also long for role models who can expand what is possible for them, inspire ambition and demonstrate mindsets and behaviors on how to develop themselves fully and how to be their own advocates.

I was inspired by the hope and determination I heard in the young women who spoke. Even though they know it will not be an easy road, they want to be on it.

Entering into this study also enhanced the importance of collaboration among the Good Shepherd sister leaders and their partners. The passion and commitment of Theresa and Lily was evidence of how they embody the charism of Good Shepherd and believe that the sisters and partners in the other 72 countries around the world will be inspired to follow the same human rights frame for their work with girls. And, of course, they hope other groups worldwide who work with girls will do the same.