Since 1980, Mercy Sr. Marilyn Lacey has worked with displaced populations in the United States and in refugee camps overseas. For 21 years, she served as the director of a number of refugee and immigration programs at Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County in northern California. In that capacity, Lacey and her team welcomed and resettled newly arrived refugees from all over the world, providing housing, English-language education, job placement, family counseling and more.

She also spearheaded special programs for elderly and young refugees, including the only refugee foster care program in California, which places unaccompanied minors into U.S. homes. Lacey also managed an immigration law program that assisted migrants with issues such as citizenship and family reunifications.

Through her work, she had the opportunity to visit South Sudan in 1992, and the experience vastly altered the course of her life and work. In 2008, Lacey founded an organization called Mercy Beyond Borders to aid women and girls living in extreme poverty in South Sudan (and, eventually, Haiti). She spoke to Global Sisters Report about the culture of the war-torn region and the work Mercy Beyond Borders is doing.

GSR: You have described South Sudan as 'the most devastated place' you've ever seen. Can you elaborate?

Lacey: When I went in 1992 when the war was raging, it was the time that the Lost Boys were straggling out of South Sudan. It was a horrid, horrid time. Upon arriving at a refugee camp, I saw such emaciated people, like 20,000 of them. I couldn't even believe they could stand up. The vastness of the suffering just shook me to my core. I had worked in refugee camps; I thought I was accustomed. I had never seen anything to this scale or horror. It really reminded me of Ezekiel, where he sees this vast field of skeletons. I thought, 'Someday I will try to devote myself to working with the survivors, particularly the women and girls.'

What about the culture of South Sudan makes it especially challenging for women and girls in particular?

Basically, women in that part of the world are considered to be less than human. They are told from the time they're born, 'You are worth less than a cow. You will serve your brothers and your parents until you reach puberty, and then you will serve your husband.' They don't send [girls] to school; they don't accord them any personal dignity.

It's very entrenched in their culture because for a boy to get married, he has to give a dowry of cattle to the wife's family. So the only way a family that has several sons can keep getting cows is by marrying off their daughters very young. It's a circular thing that is very hard to break through.

Is the culture changing at all?

If there is any silver lining to being in a refugee camp, it's that in the camps, women and girls saw females who were living with purpose — as teachers, doctors, pilots, United Nations administrators, social workers and nurses. Now the women want education for their daughters — what they didn't get themselves. They see that things have to change, but the men are still very much resisting that.

What kind of work has Mercy Beyond Borders done to help the women and girls in South Sudan?

We are affiliated with a primary school for girls, started by the bishop in 1994. Regarding his reasons for starting it, he told me: 'For 50 years, I have been educating boys. What did I get? War. Now, I'm going to educate the girls.' Currently, we pay the whole budget of the school, and it is really our flagship project. It is a boarding school and it is very challenging to convince Catholic families to send their girls to school, but currently, we have 702 girls there, from as far away as Darfur.

And right now, Mercy Beyond Borders has 131 girls on high school and university scholarships — the first cohort of educated girls. It's a huge change for the country. We already have 20 graduates, and there is no brain drain. They're all in South Sudan nursing, teaching, doing IT work. They were snatched up immediately for jobs. It's very heartening, though it is a long-range project, of course.

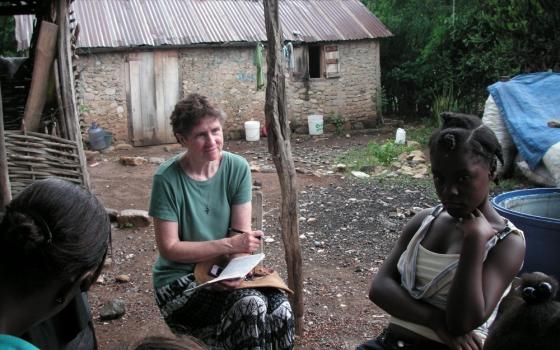

With women, we go directly to villages. We refuse to work in the capital city — that's where all the NGOs are, sitting in their air-conditioned buildings. We deal directly with women, and we teach them microenterprise and literacy. We are really making a tremendous change in their lives because it's more than learning literacy. It's learning, 'You're a human being. You're accepted. You have talents.' That's the kind of transformation we are seeing.

[Georgia Perry is a freelance writer based in Oakland, California. She's contributed to several print and online magazines including, The Atlantic, CityLab, Portland Monthly Magazine and the Portland Mercury. She was formerly a staff writer at the Santa Cruz Weekly in California. Follow her on Twitter @georguhperry.]

______

Read about Lacey's experiences of finding God in the populations she has served in her book, This Flowing Toward Me: A Story of God Arriving in Strangers.