Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, noted for serving needs of political prisoners and their families for the past 40 years, have intensified their efforts to address "new patterns" of human rights abuse, according to Sr. Crecencia Lucero.

In an interview with GSR Lucero reflected on challenges, successes and “heartaches” of the four-decade history of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines. As co-chair, she explained there are evolving challenges facing task force members. The sisters are adapting to respond to their community’s constitutional mandate to witness to God's reign of justice, peace and integrity of creation.

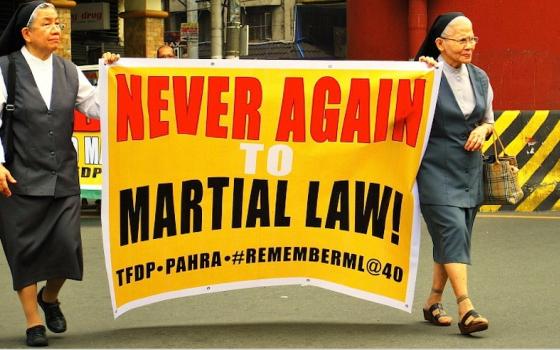

The Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines (AMRSP) established the task force in 1974 to assist political prisoners when the “dictatorship” of the late President Ferdinand Marcos banned organizations. TFD provided moral spiritual, legal and material support to prisoners and their families. Franciscan Sr. Mariani Dimaranan, an ex-political detainee, directed the organization until 1989, when Lucero took over as director. Dimaranan continued as chair until her death in 2005 at the age of 81 years.

Lucero, 72, also serves on the board of the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development.

GSR visited her office at Saint Joseph's College, Quezon City in April.

Martial law declared in 1972 was lifted in 1981, and democratic institutions were restored after the 1986 Manila uprising ousted Marcos. Why does TFD continue?

There are still more than 300 political prisoners. The government keeps denying this by saying they are criminals arrested for arson, murder and other crimes. Analyze why these people were arrested and detained – it's for political or ideological reasons. Many are detained for at least six years only to have their cases dismissed when they have already served almost the entire sentence – if they had been convicted. There are forced disappearances, which the state also denies any part in. In 40 years of TFD we have gone through six presidents, and we still have thousands upon thousands of arrests, tortures and forced disappearance. Killings continue unabated.

Have there been success stories with detainees?

We have helped to free 90 to 100 detainees a year, but there are more new arrests than people we have been able to help get released. We go very slowly. For sure we need good lawyers. Most of the time we only have paralegals. We do not have the money to pay for the lawyers. We do have some FLAG [Free Legal Assistance Group] lawyers.

How did you come to be assigned to succeed Sr. Mariani Dimaranan?

When she would get sick in the late 1980s and early ‘90s I helped her out. I took over as director of TFD in 1989. She was strong enough to continue as chairperson, and I just came in to do some of the work. But I think it was because during my formation years I was already with her in many human rights activities. I was going from prison to prison looking for those who were arrested or had disappeared. We young sisters went to morgues looking for people reported to have disappeared or been arrested.

It must have been depressing to work with torture victims and killings and to deal with their grieving families.

Our only thought then was to support – be one with the families of the victims. At that time our leaders and whole congregation was so supportive to families of those being tortured. Perhaps I was schooled in that work so it is in every fiber of my being. Also, once you see that situation and stick your hand out to them, you reach the point of no return. So when Mariani was getting very sick, then I took over.

What is different about justice and peace and human rights work after 40 years?

Patterns have changed. Now injustice is also about the Muslims and the Lumads [indigenous people in Mindanao, southern Philippines] who are fighting for their ancestral domains.

Theirs is a double struggle: they fight against the government, which is taking over land even if it is planned as ancestral; and there are mining and other companies who want the resources of their land. Many Lumad leaders are arrested and tortured because of the mining. Our data shows many IP [indigenous people] and their relatives who have been killed. So now, our work has expanded to justice and peace and integrity of creation. We address mining, logging and other development issues in the context of how they violate rights of IP and their communities. Our response is based on the premise that IP have rights to their land, right to their subsistence. If you take their land, you take for them their means to subsist, their right to form their community and preserve their culture.

What activities do you do in this regard, aside from supporting protests of the communities?

Franciscans have the Fellowship for the Care of Creation Association Inc. registered with the government. It was established originally in 1987 and now trains farmers in sustainable agriculture and organic farming. It has projects in Santa Anna, Cagayan [northern Philippines], Toril, Davao City [Mindanao] and one in Subic, Zambales, [Northwest of Manila] with the IPs. We work to transfer knowledge and technology for sustainable farming at the training site itself, and all the farmers surrounding the site.

How is your group different from the many environmental NGOs doing similar work?

Our program is based on “creation spirituality.” St Francis Assisi is the patron saint of ecology, so we have developed a program of spirituality of ecology for the different sectors. We hold farmers' training and at the same time we go to schools and parishes and give an orientation on mining, logging and other industries in their area that impact the environment, and the connection to human rights. When we tackle logging we trace its impact on flooding and other natural problems communities are facing. The teachings we give are about politics and economics. We are now into watersheds.

The orientation we give is the same as what our sisters in formation undergo. We encourage our people to become more involved with Mother Earth through gardening, planting trees and produce. Mother Earth is part of the program’s spirituality. In caring for Mother Earth, we are also caring for people who need the food, have the right to life, the right to clean air and so on. Most of these rights are not highly understood as human rights subjects as much as political detainees’ rights are recognized.

Has your life ever been threatened directly for defending human rights?

No. I was almost arrested in 1985 during a very big rally against oil price hikes. I was in the front line when police fired water cannons at us and herded our group into a van. I saw two young men with blood oozing from somewhere on their heads. They were seminarians. I told the arresting officer, “If these two guys die, their death will be in your conscience for the rest of your life,” because I saw their batons had nails. I took my hankies and pressed it on their heads.

When we were at Camp Karingal, the arresting officer told me to stay with the two men until we could take them a nearby hospital. I called the major superiors and TFD from the hospital to tell them about the arrest and wounded. Back in camp, we saw, lo and behold, the grounds were filled with so many priests, nuns, seminarians I had called. The arresting officer got nervous. He told me to just bring the men home, so we were not in the blotter.

Task Force Detainees got embroiled in the split of the Left. How was that settled?

The case is ongoing. I was the executive director in 1994 when the extreme Left was breaking up. TFD leaders were also leftist in the sense that we were working with the movement towards democracy and civil rights. We accepted all people – “subversive,” “New People’s Army,” whatever ideology, creed or race – everyone has human rights.

We on the executive committee became aware of the internal problems of the Communist Party of the Philippines, and people came to talk me into joining their faction. We said TFD is a church organization so we could not go with one side or another.

In mid-1995 a group broke off from TFD after the split in the Party. I was surprised when 13 of the 15 TFD regions went to the breakaway group Karapatan. The National Capital Region and Western Mindanao stayed as TFD.

It really broke my heart. Marani was in very bad health having had a heart bypass and then complications. I came back in 1996 after studying from 1994 for my master’s at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., and went back to work at TFD.

We had to do the very difficult work of rebuilding TFD, including starting to build up funding partners. The funds we raised in 1993 had already been given out to the 15 regions. We had almost 300 full-time staff at that time. We had provided computers and two-way radios, only for the regions to break away. They took all these with them, including all other facilities, cameras.

So the case continues. They want access to the documents up to 1995 when they broke away. They want at least two-thirds of the market value of the properties put together up to now. That’s the ongoing case. It's really sad.

TFD is still one of the country’s largest national human rights organizations – bigger than Karapatan in terms of its scope of work because it is involved in the economic, social and political aspects of human rights work. It is not just confined to the problem of detention.

How do you maintain this?

TFD has been registered for a long time as being independent and has more than 200 active members. Members may belong to other organizations, and that is how we do networking. I have to regularly lobby for different funding partners for the task force. Most of our funds come from Catholic organizations in Europe – Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and some from France. We also get money from the U.N. for victims of oppression, the European Union and the U.S. Democracy Fund.

How is TFD related to the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development?

TFD is a founding member of Forum-Asia, which was founded in Manila in 1991; it has grown into a big regional organization registered in Geneva and with an office there. We have other offices in Bangkok and Jakarta. I’m member of the executive council and treasurer, and we campaign for protection and respect for human rights in Asia, especially in countries with little freedom such as Bangladesh, India, Cambodia and Burma. We engage the ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] inter-governmental human rights commission.

What keeps you going?

Being invited by the U.N. to be part of this international quest for respect and protection of human rights is one of the things that make me say I have lived a full life. I tell the Lord every night I am ready any time, “Take me. You have blessed me with so many opportunities.” So when I have to travel, I put my things in order, even my bedroom. Anything can happen.

As a person and as a religious what do you gain from this work?

I gain the strength the courage and the knowledge and assurance that God is with me. There is his abiding presence along with the Spirit and Mary. That even if I have been branded a Communist, as an activist, as a nun-activist, as long as I can say, “Lord you know what I am doing and you know it is not for me, you know it has never been for me.” All this has made my vocation clearer and more meaningful to me. It has become a passion.

[N.J. Viehland is NCR's correspondent in Asia.]