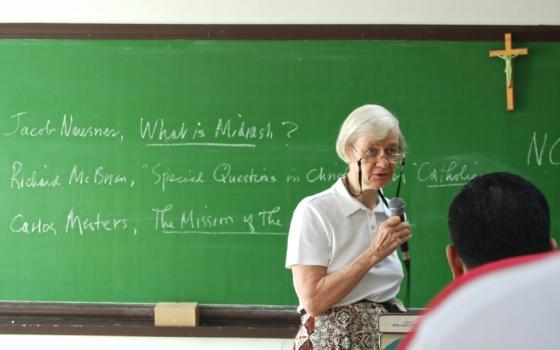

"Was Noah a good guy or not?" Maryknoll Sr. Helen Graham asked a dozen young religious, most in temporary vows, in her theology class at the Institute of Formation and Religious Studies in Quezon City, Philippines.

He built the ark and saved his family, she said, but could he have done more? Argued with God, as Abraham did?

"Don't just accept these stories," she told them. "Think about them."

Graham is vivacious and engaging in her presentations, and her energy belies her 79 years. She teaches four theology classes in three different institutions, plus has some long-running Bible study groups she meets with in the evenings and invitations from other various groups. She has been at the Quezon City institute for 49 of the 50 years she has spent in the Philippines.

Her grandparents raised her in Queens, a borough of New York City, after she became an orphan by the age of 5. When her grandmother scolded her for throwing away food that could have fed "starving children in China," she became fascinated with missionary work. Graham's grandfather was an agnostic who challenged what she learned in Catholic school. Arguing with him became the foundation for her love of theology, she said.

She was instrumental during Ferdinand Marcos' martial law years in bringing the stories of those who were imprisoned and tortured to the world. She began to visit the imprisoned, first a woman who was formerly a student, then others. She would write their stories, mimeograph them and distribute them.

She was one of the founders and a member of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines. She wrote for Amnesty International and provided detainees' torture accounts that were presented before the U.S. Congress. As part of her work with the task force, she met with members of Congress and President Jimmy Carter's administration who came to the Philippines.

She is the author of four books and numerous articles. Her 2007 book Sing O Barren One: And Other Essays on Biblical Themes won the Gintong Aklat (in English, Golden Book) Award in 2008 and the Cardinal Sin Catholic Book Award, given by the Asian Catholic Communicators Inc. She also received the Mentor Award for 2012 from the Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession of Society of Biblical Literature.

At the Institute of Formation and Religious Studies, she teaches and mentors students from across Asia and from Africa, conveying her passion for biblical study and teaching. The library at the institute has been rededicated in her name, "and I'm not even dead yet," she said, laughing.

She took time during a break in classes to talk about her life, teaching and work at the institute.

GSR: Why is it so important for women religious to learn theology?

Graham: Men have the upper hand in the church. They have at least four years of training before they are ordained. With women, you used to come into the convent, and they put a habit on you and sent you out to teach catechism. And what did you teach? You taught what you learned: often nonsense. So that's No. 1 — you become professional, and you are capable of teaching at a higher level than they grew up with. The community deserves it.

The other thing is you need it personally. You get to be a certain age in religious life — around 40 — and people start leaving. It's a question of having something that's more deeply meaningful. Studying theology and Scripture gives you a stronger foundation for what you're doing. You're not just a nun with a habit on.

It gives them a deeper understanding of their faith. It is vital for them personally, it's vital for their work, and it's vital for the church.

Is there a difference in teaching seminarians and sisters?

I find the seminarians more difficult to change their mind, their way of thinking. They're pretty set. A big number of them are apologetic, doctrinal, whereas the sisters are willing to change their mind, their way of thinking. I find them more easy to do that with.

In schools in the Philippines and elsewhere in the provinces or rural areas, you copy down what the teacher puts on the board, and you spit it back out, you memorize it. That, to me, isn't education. That's schooling that destroys education.

Why did you stay in the Philippines all these years?

I fell in love with the people and teaching. It gives me life.

I didn't come here by choice. I was assigned, and I wasn't happy. This was right after Vatican II. Being someone from pre-Vatican II, you kept a schedule, and then you're missionary by nature, so you have this conflict. That had a toll on many of our sisters. But I came here, I fell in love, and I stayed. I'm staying until I fall over.

You never asked for reassignment?

No, I never did, so I'm stuck here until I'm incapable of teaching or until I fall over dead, whichever comes first.

I started teaching when I was 30. I didn't have a master's degree yet. I was the one who assigned myself to get a master's. I joined the education committee and assigned myself to school. All the way along, nobody sent me to school. I sent myself to school.

I then went to Berkeley and got an advanced master's. And 10 years later, I got a doctorate here. So it took me four decades to get all my education; meanwhile, teaching, teaching, teaching. But when I hit my 60s, I said, 'Now, I'm a teacher.' And that's when you have to retire here.

It's a pity because as a teacher, I'm better in my 60s and 70s than I was earlier. Obviously I know more. I don't care about assignments and tests and exams. They learn by enjoying themselves. Whereas when you're young, you're rigid about this and that.

What do you teach? Mostly Old Testament?

I've taught Synoptics, I've taught Paul, I've taught hermeneutics. My preference is Psalms and Torah and prophets, so now I'm teaching Psalms, Torah and prophets.

What is the most challenging part of what you do?

I guess trying to get to a level so they really understand. I give them material that is difficult to read.

I don't just start with baby stuff. It's a challenge to be sure they're understanding what is going on, which is my major concern. I give them papers to do. The seminarians call them 'bloody papers' because they come back all red.

I'm concerned that they learn. That's all I'm for, so whatever will help do that is a challenge to me so they will really learn intellectually, but that it will also be a spiritual nourishment for them so it's not just intellectual learning for them. I don't give exams; I just give these papers, which is like a conversation back and forth.

What is most rewarding about your work?

That they learn. The most wonderful thing is to see them begin and then graduate and see how they have progressed.

I have one student from mainland China. She fell in love with the Old Testament. We sent her to Loyola School of Theology because we couldn't give her all the languages then got her into the Catholic University of America in Washington. We have a Maryknoll China program, so she got into that. She graduated with a doctorate and is now teaching at a seminary in China. That is rewarding.

Another student went to Berkeley. She is now part of the Women of Wisdom program there. Last October, Sr. Julia Prinz of Verbum Dei, two other Verbum Dei sisters and I went to China and Myanmar to gather [Institute of Formation and Religious Studies] graduates together. It was heartwarming for me to see that our graduates are in various leadership positions and are contributing much to the church.

How do you see the Holy Spirit in your life, through you and in your work?

My spirituality comes mainly from Jewish tradition through rabbinic commentary on the Scriptures, not so much from Catholic devotional material. I pray in the mornings. It is vital, and I have my 'aha' moments. With Judaism, there's no difference between study and prayer. They're two sides of the same coin so that in the process of studying Torah, you get insights. You say, 'aha,' and you stop to pray. That's what I want to happen to them.

[Gail DeGeorge is editor of Global Sisters Report. Her email address is gdegeorge@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @GailDeGeorge.]