After putting on our teal volunteer vests, we were told to line up as we waited for migrants to enter the Catholic Charities building in McAllen, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley. The space looked like a thrift store within a gymnasium: clothing racks filled the room, tucking away the makeshift soup kitchen set up in the back.

I was there as part of a Border Witness Program, a weekend retreat intended to immerse its participants into the realities of the border. The program is organized by a female empowerment group known as ARISE (A Resource In Serving Equality), which has Mercy associates as its leaders.

The director told us it's customary to applaud as the migrants walk in, adding that we would understand why once we see them.

When the heavy double doors swung open, a train of tired-looking people entered single-file, most of them carrying a baby or holding a toddler by the hand. They mostly walked with their gazes to the floor, but they lifted their heads at the sound of applause. They smiled shyly as they made their way to the check-in table.

All the numbers and statistics I had read and written about, these distant figures, whose plight merely inspired my futile yet sincere sympathies when I read about them, now had names and faces. A father adjusting the pigtails on his 2-year-old daughter. An exhausted young mother with a young, hyper son. A guy who looked to be in his 20s, traveling alone and too timid to make conversation.

It only took one or two cases of direct eye contact before I had to hide behind a fellow volunteer to cry freely, embarrassed that I was the one bawling while the migrants were in good spirits. Eventually, I caught my breath and reduced my sobs to tears while I awkwardly smiled and pretended like I didn't just have a breakdown that likely confused the new arrivals.

After all, they had just been released from detention and were now a mere phone call and bus ride away from reuniting with family members who had been waiting for them in the United States. They radiated relief.

Gaining perspective through numbers

The four Mercy associates with me that weekend would not otherwise have experienced the power of that welcoming, which was precisely why they signed up to participate in the program.

"You fear what you don't know," said Lynn Anamasi, one of the weekend's participants.

These women (three from North Carolina, the other from Florida) traveled to Pharr, Texas, where ARISE has four houses in different struggling neighborhoods throughout the city. The organization targets the region's immigrant women, offering classes and leadership training to its hundreds of members.

We began the morning of April 29 at the ARISE support center in Alamo, Texas, where Border Witness Program directors and Mercy associates Ramona Casas and Eva Soto gave an inspiring presentation on the history and purpose of ARISE.

We soon left for Upbring, a Lutheran Social Services facility, to hear community services manager Kari Rogers give us perspective. Where are these migrants coming from? How old are they? Are more coming every year?

Guatemalans, we learned, constituted 45 percent of the unaccompanied minors who crossed the border in 2015 — or, more accurately, were taken in by Border Patrol. Salvadorans were second with 29 percent, followed by Hondurans at 17 percent and Mexicans with 6 percent.

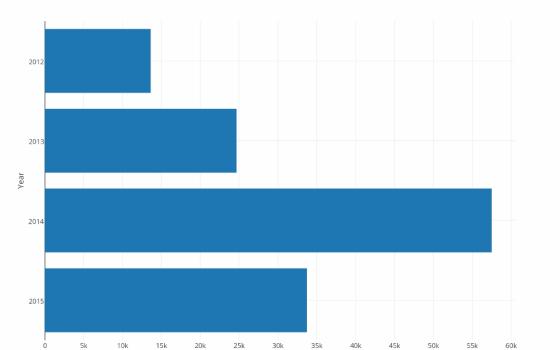

The totals vary year to year, and 2015 is the first in three years to see a decline:

About two-thirds of the minors crossing the border were 15 to 17 years old, while 13- to 14-year-olds made up 14 percent. Those younger than 12 make up roughly 17 percent of the minors.

Roughly two-thirds of minors crossing are male — a disparity, Rogers said, that could be attributed to parents feeling more comfortable sending their sons on the dangerous trek or because boys are more likely to be at risk of gang violence, making them more motivated to leave their homes.

A range of motives, we learned, prompt minors' journeys, including those common to nearly all immigrants, such as lack of economic opportunities, access to any education, or an inability to support their families in their native countries.

However, new reasons to emigrate have been on the rise, including violence at their countries' state or local level, the breakdown of laws, and the growth of transnational organizations and gangs. (In 2012, Guatemala and El Salvador each had more than 20,000 gang members.)

New Hope Children's Shelter in McAllen offers case management, medical attention, shelter, education, psychological help, spiritual care, and recreation for migrants who are 12 to 17 years old. The shelter is often close to capacity at 60.

The average stay for children in these shelters is 34 days, though Rogers said stays usually last about three weeks. Though Houston has a large resettlement program, most kids don't stay in Texas, as Central Americans tend to have more ties in the Northeast. Sponsors — those receiving the migrants in the United States — must be close relatives or family friends.

The four Mercy associates took notes around the conference table, constantly asking questions as they absorbed all this new information, voicing an eagerness to see for themselves what was going on at the border rather than leaving it at the pictures and statistics.

Because of a late sign-up, we were not authorized to visit the children's shelter and meet the minors, though Border Witness participants typically have this experience following the presentation. Instead, we went straight to the ARISE house in Las Milpas, where lunch with ARISE members waited for us.

After lunch, we loaded into the minivan once again, this time driving past the border, though not getting out of the car.

"Let's not cross or I have to stay there," joked MariCruz Azuara, a member of ARISE who obtained DACA but still has four brothers living in Mexico. "Seriously, though, I'd lose everything, and this is all I know!"

An intimate encounter with migrants

Next on the itinerary was visiting Catholic Charities - Disaster Response in McAllen, which has served about 34,000 people from 32 countries, nearly all from Central America.

This building, we were told, is essentially the migrants' last stop before meeting with family. Here, they eat, get new clothes, call their families, learn about their travel plans, load up on toiletries for the ride, shower in the trailers outside, and nap in the large communal tents if they have time before their bus departs. Most migrants come to this center straight from detention centers, and some wear ankle monitors.

We tended to a family unit as a pair, partnered up so that each volunteer was with a Spanish-speaker (like me). After the migrants received their travel information and a brief orientation from the incredibly warm and cheery Catholic Charities volunteers, we walked them through the stations and helped them gather their needs — diapers, shoes, belt, whatever — as they enjoyed warm soup and fruit at the tables in the back.

Mercy associate Ty Barnes and I assisted a young mother named Flor, whose curly-haired 2-year-old son, Jeremías, was as restless as he was precious. New pants, shirts, socks, underwear — "I think the shoes we have on are fine, but thanks!" — a purse that made her light up: Flor was always gracious, grateful and never greedy.

Each shower lasted around 30 minutes while the volunteers would stay close in case something didn't fit. Mercy associate Tracy Horton held a crying infant for 20 minutes while the mother got dressed. We agreed later that the situation had caught our attention, and we were impressed at the mother's ability to trust a stranger so easily.

That day, Catholic Charities served about 36 people.

Horton later said she expected to feel burdened by sadness and guilt — we were all reminded of our own privilege and the pettiness of our personal problems on the visit — but instead, she felt God.

"We're only as good or well-off as our faith in God," she said. "Looking into their faces, I did not see them as less fortunate or victims. I saw God's people and in that, the assurance that he knows how to take care of them better than we do. They were beautiful in their humility."

A determination to share migrants' stories

Our trip to the Rio Grande Valley coincided with the Día del Niño (Child's Day), which ARISE celebrates annually with a parade in the streets, a talent show, booths and a raffle. Though it is not typically a part of the Border Witness Program, the four visiting Mercy associates and I marched with ARISE's members and joined the community in the audience before the talent show.

That afternoon, we took a 45-minute road trip to San Benito, Texas, to visit La Posada Providencia, a migrant shelter founded by the Sisters of Divine Providence and currently run by three sisters. The property includes a few buildings for a classroom, bedrooms, main gathering space, and small yet comfortable houses, as well as picnic tables and basketball court. Since its founding in 1989, the shelter has served about 8,000 migrants from roughly 75 different countries.

Though stays can be as quick as a meal and shower, some migrants find themselves at La Posada for more than a year. While at the shelter, migrants are required to take a variety of classes, including English courses and life-skills training, and they are provided case management as well as transportation to their houses of worship.

One of La Posada's most successful stories, Cuban Joseph Rodriguez, went from a monolingual migrant who didn't know anybody in the United States to a citizen pursuing a degree in accounting full-time as he works two jobs, one of which is as the programs coordinator at the shelter.

In one house, we met several shy young women, including a 26-year-old from Ethiopia who recently had a baby and had been in the shelter for four months.

Her trek to the United States began with a bus to Kenya, a flight to Bolivia, a bus to Peru, then bus rides and long walks through the jungles of Colombia, notoriously dangerous because the police often confiscate all the money migrants travel with. She had a guide take her through all of Central America, from Panama to Guatemala and through Mexico, where she eventually found La Posada. Here, she waits to reunite with her husband, who is currently in detention in Buffalo, New York.

We ended the Border Witness Program back at the ARISE support center, where we reflected on all we learned throughout the weekend. (Our unanimous favorite memory was our interactions at Catholic Charities.) Casas then encouraged us to go around the table and share what we think are our most valuable gifts, which began as an empowering exercise and ended as affirmation that our small group had bonded far more profoundly than I had realized.

We knew that the purpose of the program was for ARISE to share life on the border with outsiders, who would then hopefully share their experiences when they returned home. Hearing these women recount the ways in which the program informed them, seeing them tear up as they recalled their encounters with migrants, and watching them tightly hug Casas and Soto as they shared their gratitude and said their goodbyes — there was little doubt that these Mercy associates were going back to North Carolina and Florida changed by the experience and eager to share their stories.

I know I was.

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Her email address is ssalgado@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @soli_salgado.]