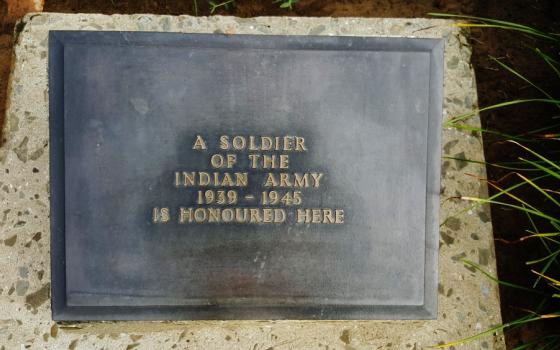

Almost a year ago, on my last day in Chittagong, Bangladesh's second-largest city, Sr. Nisha Rita Gagra took me to Chittagong's war cemetery, a site that honors World War II soldiers, sailors and airmen.

Most of those buried in the cemetery are British and Bengali. (What we now call Bangladesh was part of British-ruled India during the war.) As Gagra, a Salesian Missionary of Mary Immaculate, and I walked quietly on the cemetery's well-kept grounds on a sunny, humid morning that was about to get piercingly hot, I was moved to see the range of ages and nationalities on the tombstones. Fateh Alam of the Royal Indian Army Service, aged 50, is buried along with 20-year-old Flight Sergeant J.F.C Hawkins, an air gunner with the Royal Air Force.

The commemoration was dignified and appropriate, the official face of war. But the unofficial cost of war, usually borne by women, often remains hidden. Bangladesh is still struggling with the social costs of one such war — its war of independence in 1971.

The war ended in triumph for Bangladesh, as it successfully became a sovereign nation after being ruled by overseers from what was then West Pakistan.

Although it is still difficult to determine how many died in the war — the estimates go as high as 3 million — the war's human cost was clear. The events of 1971 caused a massive refugee crisis, with millions crossing the border into India, and U.S. support for Pakistan's military government was in no small measure responsible for part of the tragedy.

After leaving the cemetery, I asked Gagra about the 1971 war, and she was said it was a difficult and painful moment. I sensed it was not something she was eager to discuss. That's not an unusual reaction, particularly among the Catholic sisters in Bangladesh, who, by and large, are reserved and discreet about personal matters.

When I returned to the capital of Dhaka, I asked Sr. Pushpa Teresa Gomes, the Sisters of the Holy Cross' Asia coordinator, what she remembered. She was 12 years old at the time and attending Catholic boarding school. Gomes remembers the all-enveloping fear everyone felt. She also recalls attacks by Pakistani soldiers against the Hindu minority, who were targeted with particular vehemence because they were seen as loyal to Pakistan's archenemy, India.

"Many, many Hindus left Bangladesh," Gomes said. Even today, Hindus often face far greater discrimination than those in Bangladesh's much-smaller Christian community.

The experience taught Gomes to be particularly sensitive to the ways violence can be justified in the name of religion, an insight that informs the Sisters of the Holy Cross' educational curriculum, and to pay respect to the plurality of Bangladesh's religious traditions.

"Some people will cast problems as religious when they are political," she said. "When an issue becomes religious, that is when things become difficult."

When Rokeya Kabir, a women's rights activist who lives and works in Dhaka, sees the current images of refugees from Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East, her thoughts return to 1971, when "more than 10 million people took refuge in the bordering states of India."

"I was among them," she told me in an email when I asked about the 1971 war. "At that time no helping hand across the world came forward to support those refugees. Only India, at that time being a poor country itself had to support us, refugees with bare minimum of food, shelter, water and toilet facilities which Europe or the United States cannot think of."

Kabir said during the war, many girls of all classes were married off early, a dynamic not uncommon among the very poor but more unusual among the middle class or wealthy. The reason? The fear of getting raped by the Pakistan army or collaborator forces.

"At that time, people of occupied Bangladesh tried to believe that if they married off their daughters, they could escape being raped," Kabir said. "But alas, they could not be saved because being married, or unmarried, being young, middle aged, being mothers — none could escape the fate of rampant rape and killing."

The horror of those moments is one reason many in Bangladesh don't like to dwell much on that part of the 1971 war. Tens of thousands, and probably hundreds of thousands, of women were raped after being separated into camps created when Pakistani soldiers invaded towns and villages. After the Pakistanis left, many of the women had abortions.

Feminist scholars with roots in South Asia have done painstaking work in chronicling this tragedy.

Bina D'Costa, who teaches international relations and political science at Australian National University, interviewed Australian physician Geoffrey Davis, who worked in Bangladesh at the time. He performed abortions and helped with efforts that led to what journalist Anushay Hossain has called the "large scale international adoption of the war babies born to Bangladeshi women" after 1971.

And in her excellent Women, War and the Making of Bangladesh: Remembering 1971, historian Yasmin Saikia notes that Mother Teresa and the Missionaries of Charity, who had worked in the refugee camps across the border in India, played an important role in these adoptions.

However, Saikia also argues that another tragedy played out as a result: "The women who were raped and lost their babies due to abortion and adoption were made invisible, and their children become objects for others to rescue. The stories of women's and children's losses were never publicly acknowledged, lest the gendered shame wrought by the war become a national shame," she wrote.

Davis told D'Costa that the figures of 200,000 to 400,000 women raped are, if anything, low.

"Probably the numbers are very conservative compared with what they did," he said.

And then there were the rape camps. Women "would be put in the compound under guard and made available to the troops," Davis said. "Some of the stories they told were appalling. Being raped again and again and again. A lot of them died in those camps. There was an air of disbelief about the whole thing. Nobody could credit that it really happened! But the evidence clearly showed that it did happen."

Kabir said the "bleeding underneath the scars of 1971 are still surfacing." Earlier this year, Bangladesh newspapers reported on a "war child" who was adopted by a Canadian couple and came to visit Bangladesh to search her roots.

"She went to Chittagong to her village but could not trace her family since at that time proper records were not maintained," the result of "avoiding the social stigma of the unfortunate young woman who was raped and had to bear the baby and could not keep her after the birth," Kabir said.

There are so many other stories like this, of rape survivors who were not welcomed back into their communities or families because of the shame. Or the fact that women did not find their proper place in what Kabir calls "grand narrative of the liberation war."

"They sustained the agriculture economy; gave food and shelter to the freedom fighters; worked as informers for helping the freedom fighters; [transported] the arms under cover from one place to another, collected medicine for freedom fighters. Some even fought as combatant with arms," she said. "Their stories are still being ignored by historians."

In her book, Saikia says that is all too true: Official histories rarely acknowledge or commemorate women's experiences.

The good news is that scholars like Saikia are placing a needed spotlight on experiences and histories that deserve to be drawn out of the shadows.

Groups like the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security are doing related work, documenting and promoting the role of women in various peace processes in the world. Melanne Verveer, the institute's executive director and a former U.S. Ambassador for Global Women's Issues, told GSR editor Gail DeGeorge recently that it is important to stop viewing women as victims.

Through institute publications like "Women Leading Peace," which provides case studies of women in peace processes in Northern Ireland, Guatemala, Kenya and the Philippines, and in several segments of Fast Forward — How Women Can Achieve Power and Purpose, which she co-authored, Verveer stresses the importance of women being involved at all levels of peacekeeping.

"I'm trying to show the many ways women today are using their power for purpose and to say that wherever we sit, we have the power to make a difference. My hope us that we can grow progress for women and girls around the world," Verveer told DeGeorge.

Sexual violence continues in wars, including the ongoing conflict in Syria.

"The reasons for war and the use of violence against the vulnerable, especially women, children and the elderly, is a pattern repeated in all wars and in all parts of the world," writes Saikia, who notes that the notions of humanity are constantly violated in war. This is why women religious, with their strong belief in the embrace of humanity, are often on the front lines of war and its impact, Verveer said.

The sisters' work in the wake of war is inspiring. But the need for it is a reminder that, sadly, the effects of war don't end at war cemeteries.

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]