In November, Sister of the Good Shepherd Glynis Mary McManamon opened Shepherding Images Studio/Good Shepherd art gallery in Ferguson, Missouri. Her gallery opened just in time for the anniversary of a grand jury's decision not to indict Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson in the August 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown — the event that sparked the Black Lives Matter movement.

McManamon recently spoke to Global Sisters Report about God, race and the ability to find spiritual healing in art.

GSR: How did you become an artist?

McManamon: I was raised in a family where I was around art supplies. My dad was always trying to get himself syndicated as a cartoonist, and my mother wanted to be a fashion designer. But I didn't see myself as an artist. In high school, I didn't take art because I didn't think I was that good.

I entered religious life in 1976, bouncing from one ministry to another, trying to find my place. I worked as a secretary, I worked in pastoral care, I worked in public relations and in fundraising. Finally, I asked to get an MBA, which I got, and I did a concentration in personnel. I got a certificate to be a drug/alcohol counselor and then kind of had what used to be called a nervous breakdown.

I didn't know what it was and couldn't figure it out. But during that time, I couldn't work as a counselor because I had — I'll be frank — clinical depression. I needed to focus on myself, and I was spending a lot of time in chapel, journaling and reflecting, and I had a sense of God saying to me, 'You keep telling me who you are and what you're going to do. Now listen to me tell you who you are. You need to talk to your province leader and tell her that you are called to be an artist and ask for a sabbatical and take a year of study.'

So, in 1998, I took a year of studio courses at Bellarmine University. The thing I had always had a heart for was icons, so I started to experiment with that form by taking a course in iconography. In 2002, I went to my first icon retreat, which was eye-opening, and it took off from there.

Art then became your primary ministry?

At first, the other sisters would say, 'I get that you're going to do art, but how are you going to minister?' And part of what I would say is, 'My art is going to do the ministry.' Nowadays, they don't have a problem understanding that because they've seen it.

You can say things in art that you can't say in words. I haven't seen people get excommunicated for what they've painted. I have seen people get excommunicated for what they've said — not that I'm saying anything that is against the church. It's just that I think it's much easier to interpret words than to interpret images.

And you still do icons?

There's two ways I use icons: I do what I would say are Orthodox, meaning that they would be liturgically, canonically acceptable in the Orthodox or in the Eastern Catholic churches. But I use the style of icons to make observations about today's world. For example, I did a series of Marian images, and I portrayed Mary as in different situations as a modern woman but using the icon style. In one, I portrayed Mary as a Catholic mother in Belfast, Ireland, and Jesus as a Protestant little boy in her arms.

They're not traditional because there isn't a precedent, and in iconography — at least, what I have grown to understand from studying with different people — ordinarily, you follow tradition, so you don't come up with new icons on your own. Your icons should be representative of a tradition. To do a new icon in that tradition, you have to be guided by your spiritual director. And ordinarily, you would fast, you would pray, and then you would present and your spiritual director would help you to understand whether or not you are truly called to do that. And then you'd go ahead. Fortunately, I'm Roman Catholic [laughter], so I'm not really bound by the canon.

I've also done deisis for our congregation. Deisis are prayer icons, and the central point is Jesus enthroned and then Mary is on left and John the Baptist is on his right.

How did you end up in Ferguson? Was that an intentional choice?

Well, I didn't choose Ferguson; Ferguson chose me, if that makes any sense. I had been 20 years in Louisville, Kentucky. In 2006, I opened a Shepherding Images, and that was my studio where I showed my own art. I had that until mid-2010, when I was transferred to St. Louis.

In St. Louis, I spent five years working in administration and human resources, but after the election of our new province leader and dialogue with her, she said, 'What do you want to do?' I told her I wanted to go back to an art gallery, and I was told I could do it anywhere.

I went back to Louisville for a week to kind of scope it out, but I didn't hear God saying anything enthusiastic. I'm from Cleveland originally, so I thought, 'Oh, I'll go back to Cleveland.' No. I thought, 'I'll go to Columbus. My sister lives there, she knows some artists.' No, that didn't fit. So then I started to get a sense that I was going to be staying in St. Louis.

In St. Louis, I was calling realtors and not getting called back, so an Ursuline sister who works as our assistant treasurer said to me, 'Why are you not looking at Ferguson?' Well, I had said from the beginning 'not Ferguson' because I had been on West Florissant, and it didn't look like a good fit. Ferguson was in the news, yes, and, yes, there was damage there, but that wasn't my concern. It was simply that it didn't fit. But she suggested downtown Ferguson, where I had not looked.

So I got a realtor and that afternoon, she had me in a place. It didn't work, but the owner said his partner was renting a place across the way, and that's where I am today. I went over there, and it just felt right. The space was saying yes.

You've said that the mission of your gallery is to share the values of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. I'm interested specifically in the values of reconciliation and individual worth and what they mean in today's Ferguson.

Well, the first thing I want to say is that Ferguson is everybody's city. I like to say the country is like the Butterball turkey, and Ferguson is like the thermometer. The whole turkey got cooked, but the thermometer popped up here. And in Baltimore. And in Cleveland. People want to point the finger at Ferguson and say, 'Oh, what a terrible place.' Well, in this country, as a whole, racism is still really, really prevalent. And it's subtler than maybe it was in the past, which makes it worse. Individuals may be very open-minded, but as a society, we have certain constructs, certain language, certain ways our minds sort things out, ways we value or devalue things. That's the first thing.

Second, there are struggles here that I haven't come in to solve. But there are things that I have done before I came here that I have continued to do. And I think that in a way, it speaks to these struggles without saying, 'Here I am! I'm going to show you something that you don't know.' For example, I like to make religious art showing different races.

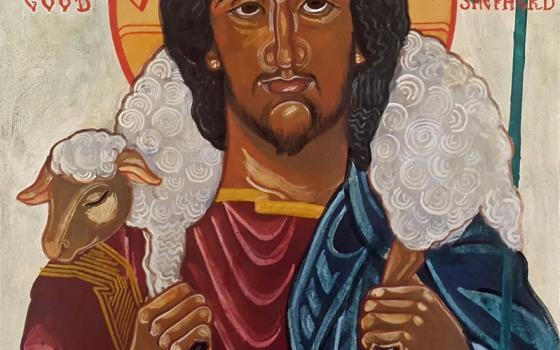

The first icon that I painted here, very deliberately, was a Christ. I quite intentionally made him black, but people don't see him that way. Indian people come in, and they see an Indian. Asians see an Asian, Mexicans see a Mexican. I suppose African-Americans see black. The only people who don't see themselves might be white people [laughter]. I don't know. But he's got wavy hair, and he's got dark skin and he's got a broad nose. He's on my business card, and when I gave my card to a lady who runs a program here, she looked at it and said, 'Oh, my God. You're my answer to prayers. Kids go to church and they don't see a Christ who looks like them.'

The other thing I do is icons of women. I've done all this research to find women who there are legitimate icons of, but they don't show up. We don't see them. Lots of people have heard of Cosmas and Damian, who were physicians. But who's heard of Hermione? She also was a healer. So I promote individual worth by having people be able to find themselves in imagery and reconciliation in the atonement for that absence.

How do you see the Holy Spirit move in art?

There are a lot of pieces that people have been offended by or that have left them cold. But I think that art sometimes shocks to wake us up, and the Holy Spirit sometimes shocks to wake us up. Even when we get very, very angry at a particular piece of art, the Spirit is speaking. The question is, what's the anger about? And what's under the anger? Usually, fear is under the anger. And what's under the fear is usually some kind of sorrow or grief. So I think the Holy Spirit can move through any piece of art, just as any event in the world can reveal to us what the Spirit is calling us to.

Mark Rothko probably isn't that modern anymore, but Mark Rothko is an artist whose art I want to not like. I don't want to like it at all — I really don't. I'd seen his work on book covers or in books, on websites. Then I saw a real Rothko, and it left me cold. But I couldn't turn away. And the longer I stood there, the more I saw, there was an energy moving in that painting. But it required contemplation. It required me to wait on it. And my mind wouldn't come up with words and thoughts and rational processing. I had to just be with it. And I think that's another way that art can allow the Holy Spirit to move, and we can connect and become aware of the Spirit because of a piece of art.

How do you see the Holy Spirit moving in your gallery?

I think in the interactions with people. It's the people who show up here who surprise me, and that's when I see God kind of playing peek-a-boo with me. There's a couple here, I don't know their story, but I know that they're both on SSI [Supplemental Security Income]. They're not that old, so they have some disadvantages that made this necessary. But when they come in here, I feel so much joy that I want to jump up and say, 'It is the Lord!' There is something going on there.

And I guess that would be the other thing, the rest of the story of how I wound up in Ferguson. One of our chaplains — after I was in the process of opening — told the sisters he was so glad that I had opened this gallery here in Ferguson, because he had been praying to Sr. Francis Mallory. Sr. Francis Mallory was one of our African-American sisters in the contemplative lifestyle who had died. He had been praying to her that the sisters would find some way to be present for Ferguson. He told them that. I didn't hear the story until the day after I opened. But, like I said, I didn't choose Ferguson.

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is a Global Sisters Report staff writer based in Kansas City, Missouri. Her email address is daraujo@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @dawn_cherie.]