The former workshop at Ravensbrück, the notorious concentration camp north of the German capital, Berlin (Dreamstime/Petr Svec)

The Vatican's stance in the face of the mass murder of Europe's Jews is a discussion fraught with moral and academic challenges. Pope Pius XII's insistence on official Vatican neutrality and his failure to explicitly denounce the Nazis have been much debated. With the passage of time, as more archives are opening up, they are shedding light on the role played "in the shadows" by individual priests and sisters as well as by congregations to help Jews and Allied prisoners of war.

Last August, a new book titled The Irish in the Resistance: The Untold Stories of the Ordinary Heroes Who Resisted Hitler was launched in Dublin. It includes the story of Franciscan Sr. Katherine (Kate) McCarthy as well as a number of other Irish nuns who were active in the anti-fascist resistance across Europe in World War II. Ireland, like the Vatican, was officially neutral during the war, so these were religious who were living in places like France, Belgium and Italy.

There have been an increasing number of calls for McCarthy's resistance activity to be honored through a film, a statue or some other tribute, in the same way as her fellow countryman, Msgr. Hugh O'Flaherty, was featured in the film "The Scarlet and the Black," starring Gregory Peck.

In May 2024, a plaque was unveiled in the French city of Béthune to commemorate McCarthy, who took the name Sister Marie-Laurence in religious life, but is better known today under her birth name. She risked her life during World War II to assist the French Resistance and help as many as 200 Allied servicemen to escape German-occupied France. She was betrayed in 1941 and captured by the Gestapo.

Cover of The Irish in the Resistance by Clodagh Finn and John Morgan (Courtesy of Gill Books, Dublin)

Incarcerated in a number of prisons, she was repeatedly interrogated and spent a year in solitary confinement before she was sent to Ravensbrück, the notorious concentration camp north of the German capital, Berlin. There, those not sent to the gas chambers were forced into hard labor. Survival hung by a thread as brutal beatings, hunger, deprivation and typhus stalked the camp's inmates.

Sentenced to death in 1942, McCarthy managed to avoid selection for the gas chambers four times, including on one occasion by jumping out of a window.

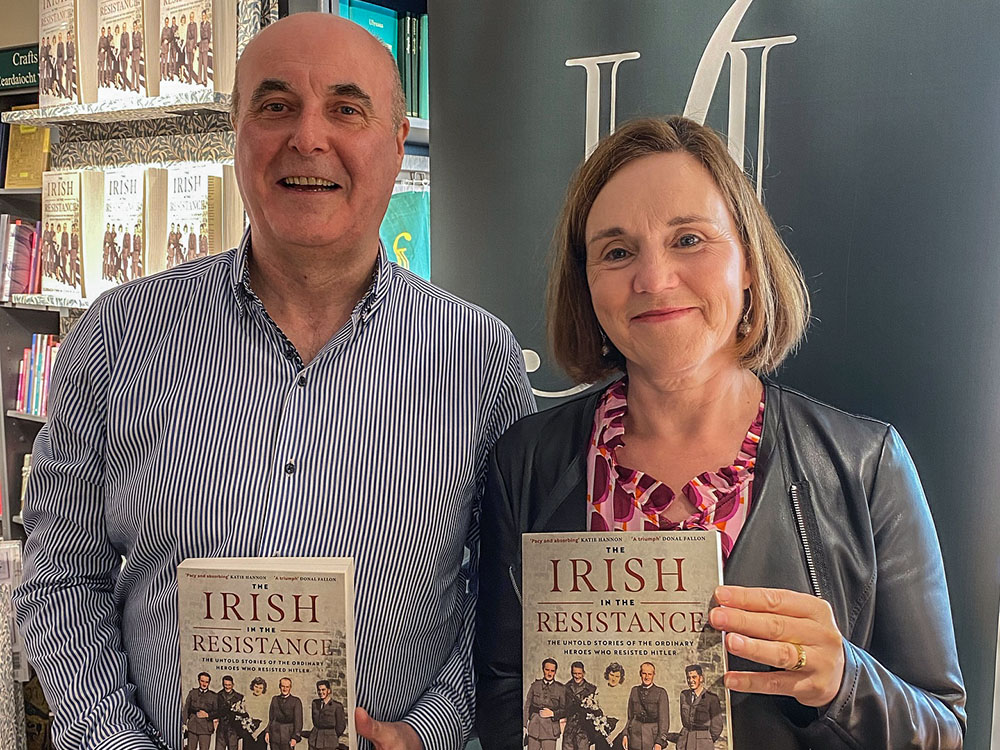

Global Sisters Report spoke to writer and journalist Clodagh Finn, who co-authored The Irish in the Resistance with John Morgan. Finn recalled how McCarthy endured "five very difficult interrogations by the Gestapo," according to the nun's witness statement. When she was freed from Ravensbrück on April 25, 1945, she weighed little more than 70 pounds.

After the war, France awarded McCarthy the Médaille de la Résistance and she was also decorated by Britain. She moved back to Cork, Ireland, and became mother superior at the Honan Home for the Elderly. "She must have been a really good administrator with lots of leadership and organizational skills," Finn said.

McCarthy died suddenly on June 21, 1971, and is buried in St. Finbarr's Cemetery in Cork.

The Irish in the Resistance has been "incredibly well received," Finn said. "People are interested in people who find themselves in very difficult circumstances and do something extraordinary to help a fellow human being in a fix."

The book sheds light on aspects of Irish history that have been neglected, including women's history. "So many women's contributions have just fallen under the radar," Finn said.

In addition, she believes the book has a resonance for our times.

"It feels like the 1930s; you have the return of authoritarian leaders across the world, you have the rise of the extremes, not only on the right but on the left, and you have misinformation and propaganda."

The Irish men and women highlighted in the book who risked their lives to resist Nazism were, for the most part, "ordinary people — governesses, teachers, gardeners, housewives, priests and nuns — who found themselves in an extraordinary situation and took incalculable risks to help another human being in difficulty," Finn said.

Authors John Morgan, left, and Clodagh Finn present their book at the launch of The Irish in the Resistance in Dublin in August 2024. (Courtesy of Gill Books, Dublin)

She paid tribute to McCarthy's fortitude despite the challenging circumstances, particularly the length of time she spent in solitary confinement.

"How do you keep your sanity? Any moment, the door could open and anything could happen. It was so immensely lonely. She had to fight with all her moral and physical strength. I suppose her faith really kept her going. In Ravensbrück, there was a lot of enforced labor. What I thought was incredible was how many of the women continued to resist in small ways even while they were in prison. They would go slow. Sister Kate did belts for paratroopers and would unpick the stitches. It is remarkable."

Born in Drimoleague in County Cork in 1895, McCarthy was 18 when she joined the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady (formerly known as the Franciscan Sisters of Calais) taking the name Sister Marie-Laurence. In Béthune, where the Franciscans transferred her, she nursed wounded soldiers during World War I.

When World War II broke out, she visited and treated Allied soldiers in POW camps and saw their need for help. She joined forces with two local women, mechanic Sylvette LeLeu and café owner Angèle Tardiveau, to hide servicemen before their escape from Nazi-occupied France. Later, the trio joined forces with the resistance network Musée de l'Homme.

Finn likened McCarthy's courage and quick thinking in evading the gas chambers by hiding under a bed and jumping out the window to that of another Irish nun who assisted the Resistance. When the Gestapo came to search Agnes Flanagan's room in Belgium, she tore up a list in front of them rather than let the information fall into their hands.

"They acted on their wits; I am just so full of admiration for them. They knew what was ahead: arrest, torture and deportation, execution. The risks were enormous," Finn said.

Born in Birr, County Offaly, in 1909, Flanagan first moved to Belgium when she was 21. She worked as a maid in Namur and later in Tournai, southwest of Brussels, where she joined the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Augustine in 1934.

She was arrested on a charge of hiding a British POW and spent time in a Belgium prison in 1941. Released on health grounds, the following year she was rearrested on a charge of having Resistance documents. After a trial in Essen, she was sent to Ravensbrück in December 1942, where she remained until the end of the war.

In a letter to a family member at Easter 1946, she recalled the last days in the camp when she thought she was going to be sent to the gas chambers. "It is a dreadful time for me this Holy Week. ... On that Thursday last year, I was destined for the gas chamber on Good Friday morning," Flanagan wrote.

Instead, she was rescued by the Swedish Red Cross. According to an official at the time at the British embassy in Stockholm, "her fellow prisoners speak of her with greatest admiration as being one of the bravest women in the camp."

Advertisement

Flanagan left the convent in 1947 and married Emile Depret. The couple had one child, Rose, who died in infancy. They eked out an existence and it was only in 1952, when Flangan was desperate for money, that she wrote to the Belgian State Commission on Pensions to say that she had, in fact, helped a British escapee by giving him clothes, money and a French-English dictionary.

She also recalled how, in 1941, she had snatched a letter from a member of the Gestapo who was searching her office and tore it into little pieces. At the time, she claimed the letter contained private details relating to her moral life as a nun, but later she explained that it contained a list of Belgian traitors that she was to send to the Allies. In May 1952, she was awarded a pension by the Belgian government.

Another Irish nun who assisted the anti-fascist resistance highlighted in The Irish in the Resistance is Sr. Noreen Dennehy from County Kerry who assisted the Vatican-based O'Flaherty and his Rome Escape Line, which hid thousands of Allied POWs as well as members of the Jewish community in German-occupied Italy.

Dennehy's work involved delivering messages for O'Flaherty. She and the Irish Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception hid, fed and clothed hundreds of Jewish women and children, keeping between 30 and 40 at a time in their convent. According to Finn and Morgan's book, the Franciscan nuns described themselves as neutral (because they were Irish), and the Germans left them alone.

Sr. Agnes (Clare) Walsh, a member of the Daughters of Charity of St Vincent de Paul, helped to save a Jewish family in France from deportation to a concentration camp. Though she was born in Hull in Britain, she acquired an Irish passport while living at one of the congregation's convents in Ireland.

She moved to the St. Vincent de Paul convent in Cadouin, France, and in December 1943, a Jewish man named Pierre Cremieux asked the Daughters of Charity to shelter him and his family. Walsh successfully pleaded on behalf of the family of five, and her superior allowed them to stay at the convent until France was liberated.

After the war, two of the children, Jean-Pierre and Collette Cremieux, campaigned for Walsh's recognition in 1990 as "Righteous Among the Nations," Israel's highest award to those who risked their lives to save Jewish people during World War II.

Of course, not all nuns who supported the Resistance or helped members of the Jewish community were Irish. You only have to think of Sr. Denise Bergon who sheltered 83 Jewish children at Notre Dame de Massip convent in France during the war.

And not all nuns who were heroic were involved in the Resistance. Finn came across the story of Irish nun Sr. Fulgentia Waller from Dundalk County Louth who died rescuing children during Operation Carthage, an Allied air raid on occupied Copenhagen, Denmark, in March 1945. A member of the Congregation of the Sisters of St Joseph of Chamberry, Waller spent 35 years in Fredericksberg, Copenhagen, teaching English at the French congregation's school.

Sadly, she lost her life when Danish Resistance requested that the Allies bomb the Nazi headquarters in the Danish capital. When one of the British planes on the expedition crashed into a garage near the Jeanne d'Arc school, other Allied planes offloaded their bombs, mistaking the flames from the crash for their target.

Of the 120 civilians killed, 86 were children, 10 were nuns and three were teachers. "She died saving children," Finn said. The school was never rebuilt.