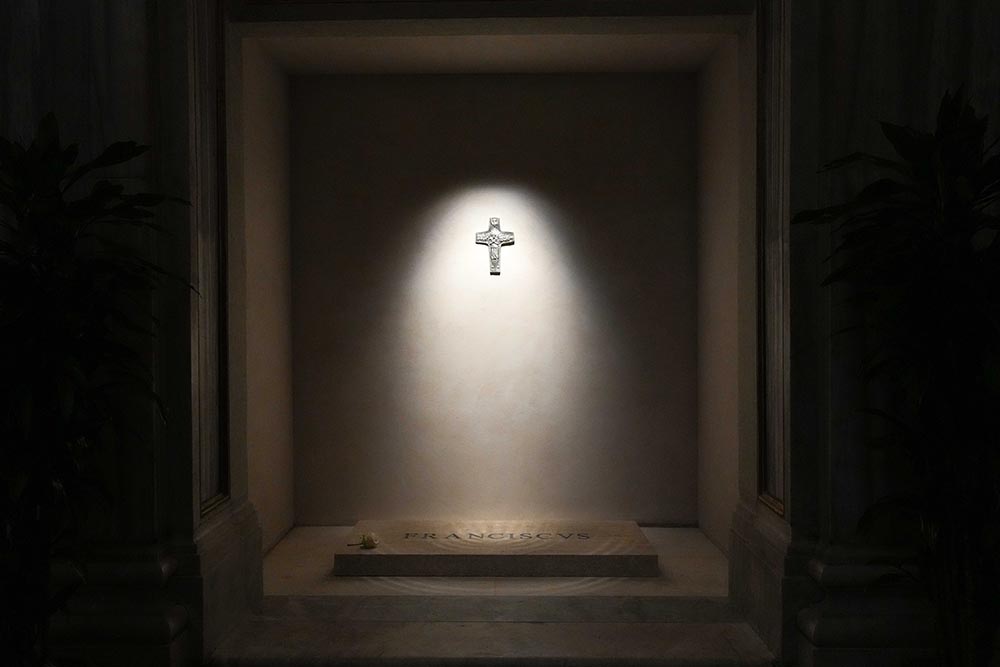

A light shines on a replica of Pope Francis' pectoral cross above his tomb in the side aisle of Rome's Basilica of St. Mary Major early April 27, 2025. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

Sr. Norma Heredia stood on a crowded Roman sidewalk drinking maté, Argentina's national drink, moments after watching Pope Francis' coffin make its way to its final stop at Rome's Basilica of St. Mary Major April 26. Something lingered in her mind: when will his canonization process begin?

Sr. Norma Heredia holds a cup of maté, Argentina's national drink, after watching Pope Francis' coffin make its way to its final stop at Rome's Basilica of St. Mary Major April 26, 2025. Heredia, of the Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Good and Perpetual Help, wasted no time in calling for the canonization of her fellow Argentine Pope Francis. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

"Pope Francis is a saint," said Heredia, of the Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Good and Perpetual Help. "We always say that. He is going to be a saint."

Like many Argentines, from Rome to Buenos Aires, she said the pope wasn't just a notable Argentine, but one "who best represented us" as Christians. He deserves to be canonized, she believes, because his joy and embodiment of mercy set an example for Christians to keep fighting, as he did, to make the church a place where no one is left out, she said.

But that process can be a lengthy one, even for popes, and only a little more than 30% of them have been canonized, said historian Diego Mauro, of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones in Buenos Aires. There is a recent exception, however, with the canonization of Pope John Paul II, whose path to sainthood took five years.

The canonization process has two long stages: beatification, when a person is considered an example for the Christian world, and may or may not require a miracle, but the second stage requires proof of a miracle for the person to be declared a Catholic saint, Mauro said.

Advertisement

John Paul II's 2014 canonization to this day faces criticism after a report surfaced in 2020 that he ignored sexual abuse of minors in the church at the hands of Theodore McCarrick, a former U.S. cardinal and Archbishop of Washington who recently died.

Regardless of the process, Argentines, in and out of the country, are mourning Francis, not just as a spiritual leader but as a favorite son, brother and father figure.

Joana Valenzuela holds the flag of Argentina outside the Basilica of St. Mary Major April 26, 2025 ahead of the pope's entombment inside. She said the pope helped young Catholics like her see the church in a more positive light and wonders what will happen now that the pope is gone. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

"Pope Francis embodied the merciful father, who dared to open the doors of the church, without hesitation, to the most excluded," Heredia said.

Some of those who felt excluded by society or the church, but loved by the pope, lined the streets before his entombment and flocked to his burial place when it opened to the public April 27.

They included Argentine Joana Valenzuela, who's been living in Italy for a few months, and waited outside St. Mary Major to catch a glimpse of his coffin. She said the pope helped young Catholics like her see the church in a different way. It became a place where they felt loved, not judged, felt included, and began seeing the church as a place where faith seemed new again. She wonders what will happen now that the pope is gone.

"He is unique and irreplaceable," Valenzuela said.

With his death and burial, "all of us cry, the entire world," not just Argentina, Heredia said.

One of those crying was Archbishop Jorge Ignacio García Cuerva, who couldn't hold back tears and took deep breaths before starting his homily in the plaza outside the Cathedral of Buenos Aires April 26. He holds the position once occupied by Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, who served as archbishop there before his 2013 papal election.

The apostles cried after Jesus' death, García said, "the way we are crying today. We are crying because we don't want death to win."

But Francis reminded people that it was good to cry, García said, and admitted to the world that he cried a lot: for people who are marginalized, for those who are tossed aside, those who are despised, for children who have nothing to eat, children addicted to drugs, homeless children, abandoned children, abused children or those used by society as slaves.

García recalled that the pope had said that people who lack for nothing or aren't attuned to the hardships of others are the ones whose eyes are dry.

Argentine Fr. Lisandro Scarabino, who joined Argentina's delegation from the Ministry of Religious Affairs, said he, too, was emotional when he watched representatives from the Eastern churches pray around Francis' coffin.

"I'm not easily moved, but this touched my heart. When they began to sing in the Byzantine rite," he said with a crack in his voice. "The thought entered: We are truly saying goodbye to a world leader, a world leader who, through his simplicity, his closeness, his message of hope, of love with a deep tenderness, as he liked to say, knew how to touch the hearts of many."

Scarabino, who represented the international ecclesial movement Fasta, said it seemed daunting when you think about what the world had just witnessed in the last 12 years from the pope who emerged from "the end of the earth" in 2013.

"And as an Argentine, I also thought about how, from a country so far away, with so many problems and divisions, such a leader could have emerged," he said. "It is something unique that we will never see again."

When the funeral Mass at St. Peter's was almost over, Scarabino said he saw a white flag in the distance that read "too human," seeming to refer to the pope, a beautiful but also painful moment he won't soon forget.

"We cry because a father to all of us has died," García said on the other side of the world. "We cry because we feel in our hearts his physical absence, because we feel like orphans. We cry because we did not fully understand or appreciate the extent of his global leadership. We cry because we already miss him so much."

The National Catholic Reporter's Rome Bureau is made possible in part by the generosity of Joan and Bob McGrath.