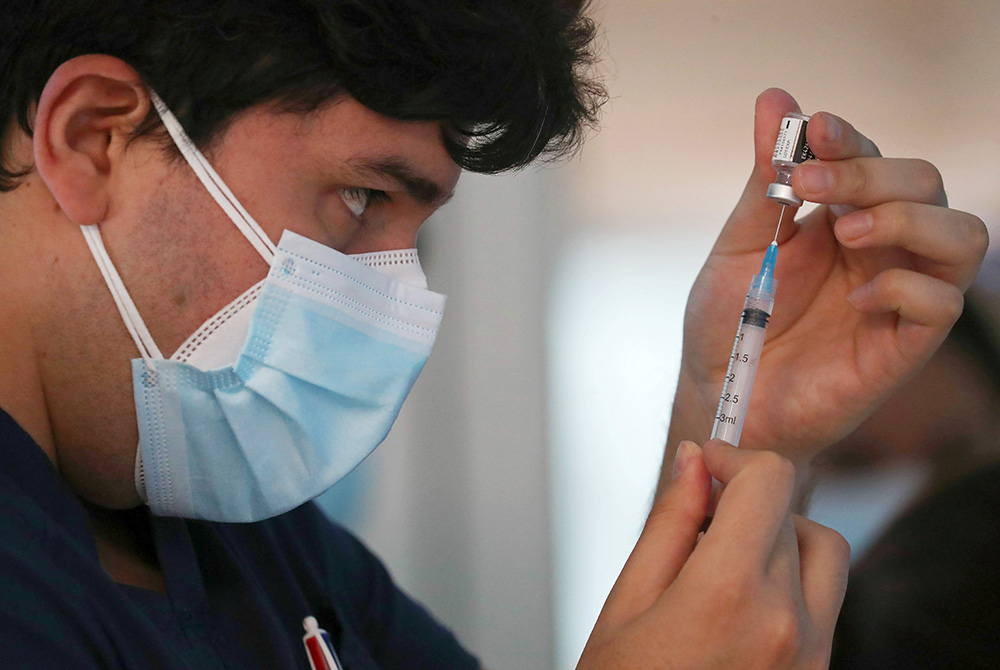

A health care worker at the Posta Central Hospital in Santiago, Chile, prepares a dose of the Pfizer/BioNtech COVID-19 vaccine Dec. 24 amid the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Ivan Alvarado)

Catholic sisters and humanitarian officials are alarmed by inequalities in the worldwide rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine, saying they pose further threats to the already-struggling Global South.

"Wealthier nations have bought up enough doses to vaccinate their entire populations nearly three times over by the end of 2021," an alliance of groups calling for a "People's Vaccine" said in December. "Rich nations representing just 14 percent of the world's population have bought up 53 percent of all the most promising vaccines so far."

Two months later, the implications of an inequitable global vaccine rollout response remain grave.

"A global immunity gap puts everyone at risk," U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres told reporters Jan. 28 in New York. "If the virus continues to circulate in the Global South, it will inevitably mutate," significantly prolonging the pandemic.

"Vaccine nationalism is an economic as well as a moral failure," Guterres said, noting that research from the International Chamber of Commerce shows that the pandemic could cost the global economy up to $9.2 trillion without support to the developing world.

"This is what happens to the supply chain when the U.S. and Europe are swooping in and buying the vaccine," said Sr. Marilyn Lacey, executive director of the humanitarian organization Mercy Beyond Borders and a member of the Religious Sisters of Mercy.

Bulgarian Health Minister Kostadin Angelov watches an Orthodox priest receive the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine Dec. 27 at St. Anna Hospital in Sofia, Bulgaria. (CNS/Reuters/Stoyan Nenov)

"This is a very serious problem not only in terms of actual lives, but the message it sends about whose lives are most important," said Emily Doogue, Catholic Relief Services' acting technical adviser for COVID-19.

The global community, Doogue said, should "avoid replicating those systems that privilege the privileged."

But that is exactly what is happening. Africa Renewal, a news project with ties to the United Nations, reported Feb. 3 that as of Jan. 25, more than 68 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been administered in 56 countries, but only two were in Africa: Guinea and the island of Seychelles.

And yet, the World Health Organization says COVID-19 cases and deaths "are surging in Africa as new, more contagious variants of the virus spread to additional countries." In a Jan. 28 report, WHO said more than 175,000 new COVID-19 cases and more than 6,200 COVID-related deaths on the continent had been reported in late January.

WHO noted that a new variant first identified in South Africa has been found in Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Comoros, Zambia and in 24 non-African nations.

"What's keeping me awake at night right now is that it's very likely circulating in a number of African countries," said Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, WHO's regional director for Africa.

Catholic Relief Services field workers carry out COVID-19 "sensitization" efforts at the market in Pwalugu, Ghana, in June 2020. The city, located in the Upper East region of northern Ghana, has been the epicenter of the pandemic in the region. (CRS photo/Natalija Gormalova)

An urgent need to 'prioritize equity'

Although the Global North has been hit harder than the Global South so far, the pandemic and the need for vaccination "is an issue that touches the whole world," said Comboni Missionary Sr. Esperance Bamiriyo, director of the Catholic Health Training Institute in Wau, South Sudan, a project of Solidarity with South Sudan that trains young South Sudanese health professionals. "People in South Sudan have not seen the worst of it yet."

Bamiriyo praised South Sudanese government health officials for their overall response to the pandemic but said they "don't have a clear idea of when and from where" the vaccine will be introduced, though she said it is likely to come from China.

China has strong ties to South Sudan, which already faced considerable challenges from an ongoing civil war that has displaced millions and caused an estimated 400,000 deaths.

People wearing protective masks wait in line Jan. 26 to receive the Chinese Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine in Belgrade, Serbia. (CNS/Reuters/Marko Djurica)

Similar dynamics exist in Syria, which is trying to rebuild from a decade of war.

Sr. Annie Demerjian, a member of the congregation Sisters of Jesus and Mary (Provided photo)

"We have not heard about the vaccine for the people in Syria," said Sr. Annie Demerjian, a member of the Congregation of the Religious of Jesus and Mary who is based in Syria. "I don't think we'll have it soon."

Nor will the West African nation of Liberia, a country still recovering from decades of war. That is worrying, given the changing nature of the pandemic's new variants, said Sr. Barbara Brillant, the dean of the Mother Patern College of Health Sciences in the Liberian capital of Monrovia.

"We may be in more trouble eventually, and it's more than what we can now handle," she told GSR, noting the pandemic is just one more worry in a country where basic services, like running water and electricity, are nonexistent for many.

Such preexisting realities, advocates say, are precisely why delays in getting the vaccine to poorer countries are unacceptable.

Sr. Helen Saldanha, a member of the Missionary Sisters Servants of the Holy Spirit and the outgoing executive co-director of VIVAT International, a global human rights advocacy organization that works at the United Nations (Courtesy of Sr. Helen Saldanha)

"This is a pandemic where all have to be protected," said Sr. Helen Saldanha, a member of the Missionary Sisters Servants of the Holy Spirit and the outgoing executive co-director of VIVAT International, a global human rights advocacy organization that works at the United Nations.

"It is the right of everyone in the world to be vaccinated," she told GSR.

Sean Callahan, president and CEO of Catholic Relief Services, agreed.

"Immunizing the most vulnerable populations — including in the U.S. and low-income countries — will be vital to safeguarding everyone's health and our interconnected economies," Callahan said in a Feb. 1 statement. "We must prioritize equity, not only because doing so will hasten the end of this pandemic. The case for vaccine equity is a moral one."

But moral concerns are running up against stark realities. The Washington Post reported Feb. 3 that the first tranche of vaccine distributed through the global consortium Covax — described by Catholic Relief Services as "an international collaborative effort to fast-track the production and ensure equitable access and distribution of vaccines" — will cover just 3.3% of the participating 145 countries' total populations.

While that "could help some high-risk groups get vaccinated," the Post reported, it is also "far short of demand."

Callahan said getting a vaccine to everyone who needs it is "an extraordinary challenge." And the pandemic and a vaccine rollout are one more layer of challenges in countries already beset with enormous problems.

Mercy Sr. Marilyn Lacey (Courtesy of Mercy Beyond Borders)

"The vaccine is not on people's minds. Survival is," Lacey said of South Sudan, where the ongoing civil war and a lack of infrastructure, including functional roads, bridges and flood control, would make getting the vaccine to people an extreme challenge.

"The thought of vaccinating 12 million people without a functioning government is staggering," Lacey said. "It's a recipe for disaster. ... I see chaos on the ground and don't know how they will pull it off."

One critical problem: lack of COVID-19 testing

To control the pandemic, some countries must first face a basic lack of information.

Brillant said a large portion of the population of Liberia are convinced COVID-19 is not real.

"The average person who goes to the market doesn't have a clue," she said. Nobody wears a mask outside, and many people do not have access to information about the pandemic.

And, even if Liberians accept that COVID-19 is real, "80% say they will pray and be safe," Brillant said.

Brillant said Liberia's Ministry of Health has done its best to educate citizens with limited resources. However, there has been insufficient testing for COVID-19, and current available numbers of those affected by the virus — 1,956 cases as of early February — probably do not reflect the extent of infections.

"We're not testing enough," she said.

A health care worker in Sequim, Washington, draws a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine from a vial in this illustration photo. (CNS/Reuters/Lindsey Wasson)

Brillant said Liberia may receive the vaccine by the end of March, but the country will have a steep hill to climb: It may not have the capacity to safely store or distribute the vaccine, and it will have to overcome misconceptions common in other African countries that the vaccine has deleterious effects, like making people impotent or barren.

"That's a hard thing to fight," Brillant said.

Oros Adia, a public health program manager for Catholic Relief Services in Nigeria, said misinformation is being spread throughout the continent, with prominent political leaders, such as the governor of one Nigerian state, calling the vaccine itself "a killer."

By contrast, he told GSR, Nigeria's Catholic leaders have done good work in urging church members in Nigeria to wear masks and maintain social distancing in everyday life.

Continued engagement and diligence will be needed in the coming months once the vaccine arrives "shortly" in Nigeria, Adia said. Officials hope up to 70% of the population will be vaccinated by the end of 2022 to achieve protective herd immunity, Adia said.

Adia said that target may not be easy to reach, but he takes heart in the fact that Nigeria was able to eradicate polio through a concerted effort a decade ago through a vaccination program that relied on public education supported by religious, political and community leaders.

"It was a game-changer," he said.

Advertisement

Still, "the trust issue" must be overcome, Adia said, as will resistance or indifference grounded in a variety of excuses, including religious suspicions and Nigerians wondering, "Why should I take the vaccine if I'm not eating?"

Bamiriyo said that reaction is common in South Sudan, as is the feeling that "God will protect us from the virus."

She described a recent trip with another sister of her congregation to a Wau market. Both women wore face masks, and other shoppers greeted them with laughter and calls of "corona."

"It gave me the opportunity to say that that mask was not 'corona,' but a way to protect us and others," she said. "God protects us, yes, but God helps the person who protects himself and others."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR New York and international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]