Dominican Sr. Laurie Brink is a New Testament studies professor at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. (Courtesy of Laurie Brink)

Before writing a book on theology and new cosmology, Sinsinawa Dominican Sr. Laurie Brink never bought the "We are all stardust" mumbo jumbo. When the subject kept coming up at a congregational virtual gathering, Brink would scratch her head, wondering, Where is Jesus in all of this?

"When I began to look at the question, I realized I had to check my suppositions," she said.

This led her to obtain a grant from the Louisville Institute to conduct a survey among Catholic sisters regarding how they view theology and cosmology.

The responses, which filled a 5-inch three-ring binder, were "revelatory," she said, particularly in how they differed between generations.

The cover of "The Heavens Are Telling the Glory of God" (Courtesy of Laurie Brink)

As a New Testament studies professor at Catholic Theological Union, Brink jokes that finding room for Jesus of Nazareth within new cosmology was about "job security." But the sheer volume of thoughtful survey results prompted a sense of duty within her to lift up what sisters have to say on science and religion while taking a closer look at the church's historical writings on the subject.

The Heavens Are Telling the Glory of God, published by Liturgical Press earlier this year, is "not the book I wanted to write," Brink said. "It's the book I was compelled to write."

GSR: Who did you have in mind as your reader? Was it mainly for sisters, or did you write it thinking it would have something to say to a wider audience, too?

Brink: First, sisters were the ones that did the survey; they were the ones I was originally most interested in. But the results of the survey — that there are generational differences in religious life — transfers to our regular life, the people in the pew. There are pretty profound generational differences that affect the theology we hold, our ecclesiology, our experience of what it means to be Catholic.

So, though the sisters were my primary interests, this I hope appeals to a wider audience because the main part of the book looks at issues of: What does science say, and what is theological reflection on that science, and how in sync is it with what the church teaches?

I was pleasantly surprised that this all is hand-in-glove. Science and theology might sound like strange bedfellows, but actually, they're not. And looking at science through the lens of faith is deeply rejuvenating.

Advertisement

How do you square the Bible with science when the Bible was written before humanity really understood anything about the universe? And what does the Bible contribute to the conversation about the cosmos?

That really was my original fear. The Bible is written when people thought the world was flat, when you have a different understanding, and it reorients how you see yourself in the world. What does that do to the encounter with the biblical text? When I was originally thinking about the question, I did not give enough credence to the power of the Holy Spirit.

Engaging the texts with a lens informed by scientific findings in concert with the Holy Spirit really opened up a whole different way of looking at some of these texts. Even though the biblical text was written in a historical context, we engage it from our context. The hermeneutics is what's different for us, the lens we use to read the text, so I can do a both/and, which I prefer.

What are the dangers of making God too small, of not appreciating the vastness of the cosmos when drawing up the concept God?

First, I think, if you take science seriously and you are a believer, then you see how magnificently huge God is. There's absolutely no way you can box God in life at the scientific findings of the origins of the cosmos. So right there, that blows out any kind of limitations we might be putting on the being we call God.

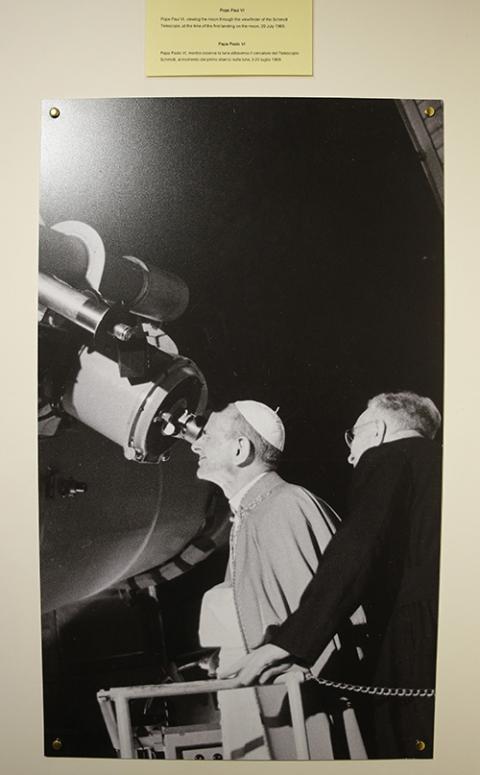

In a photograph on display at the Vatican observatory in Castel Gandolfo, Italy, in 2018, Pope Paul VI views the moon through the Schmidt telescope at the time of the first landing on the moon, July 20, 1969. (CNS/Paul Haring)

I think the magisterium has, in the context that it is in — whatever cosmology it's operating out of — has interpreted, whether it's God or the actions of God or sin or grace or any of those things, through those particular lenses. So with what has been presented, I have to kind of say, "Well, what was that coming from? And is that valid in light of what we know today?"

There's a certain amount of critical thinking as believers we need to do to figure out: How do we interpret this in light of what we have learned today? The church has actually been actively engaged in some of this. That was a pleasant discovery, to see some of our popes have been thinking about this and had been acting on it.

So it's a both/and. I think there's a responsibility we have as folks in this day and age to interpret and to do so with a hermeneutic of generosity.

How does — or how should — our emerging understanding of the universe affect or relate to religious life?

One of the arguments I try to make is that new theological thinking drawn on scientific findings should impact our ethics, how we live our life. That's true for whoever it is. But for religious sisters, it means if we are engaged with this idea of, say, the emerging consciousness, what are the implications of that? It's not enough to just say, "I really liked this concept." How is that playing out in our institutional life?

I have a chapter on the emergent disciple, which looks at the New Testament stories of discipleship in light of emergence theory and how we form people in a new cosmology in the sense of a world that recognizes that we are all a work in progress. How do the goals or processes of formation reflect that?

A view of the stars from Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado (Unsplash/Jeremy Thomas)

One should look at the vows through what I argue is a hermeneutic of catholicity: taking science seriously and seeing how it intersects with how we live our life, not just letting our theology remain in our head, but have it transformed into ethics and impact our life.

What do you consider to be the role of tradition as our understanding of the world keeps changing?

I'm a biblical scholar who has the privilege of teaching at Catholic Theological Union, where we train lay ministers, sisters and seminarians. This is a conversation we have on a regular basis: What is tradition, what is the value of tradition, how do we engage it today?

As a biblical person, I draw from Dei Verbum, which says very clearly that the word of God is both tradition and Scripture, this idea that tradition is this rich deposit of reflection on Scripture, reflection on the Christian life, and that reflection was contextual. We weren't there when some of these documents or theories or thoughts were propagated. How do we gain the wisdom of it when we are so far from its original context?

That again goes back to the idea of hermeneutics, that it has to be contextualized and you have to say, "Well, who am I as I'm interpreting this? What is affecting my interpretation?" If I believe that the word of God is found also in tradition, then there must be something in it that is enlivening, that is enriching for my soul. And it's on me to try to figure out where that connection is and not just throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Dominican Sr. Laurie Brink (Courtesy of Laurie Brink)

When you allow yourself to think most creatively or into a distant future, how do you think religious life could look different if it were to fold science into tradition? How could it shapeshift without really losing its essence?

That question is a perennial one. I think a lot of religious congregations are looking at the signs of the times and really attempting to seriously address it within their institutions. Religious life, as long as it looks out in order to look in, will be just fine. I think it's when all we do is look in that we lose sight of the wider context.

How did writing this book and wrestling with these questions and concepts affect your spirituality or understanding of the Gospels? Was there a personal evolution happening alongside the process?

As I say in the book, I was a hater, as were many of my peers in religious life. I have a deep affection for the tradition in the church and the people of God and the whole mash-up that is us. I was deeply suspicious.

And what I discovered was, the suspicion was because what had been presented about science and theology was not always accurate or deep enough for me. The "aha!" moment was when I actually looked at what the science said and then separately looked at what theologians were saying about similar concepts that I was able to see that this fits with what we say we believe.

Trilobite fossils in a slab of stone (Unsplash/Wes Warren)

I think part of the problem in some of the writings on the new cosmology is there isn't a critical enough presentation of the science, so a general reader doesn't really know where they're drawing some of their conclusions. I try to address that.

What do you hope is the reader's takeaway, and does that takeaway differ depending on whether or not that person is a religious?

What I hope people take away is that there are differences among us, and those differences don't have to be divisive, and those differences are not disloyalty. They, for the most part, are generational.

I didn't live when Vatican II was going on. I didn't know the church before that, so I don't hold the same feelings about the institutional church that some sisters who did experience that have. The youngest coming in — the millennials who are in religious life — have a totally different experience at church. Let people respect their experiences and not somehow think they don't measure up because their experience was not my experience.

The other takeaway is that science is pretty cool. And in the amazingness of God, the human mind is expanding and understanding the world more deeply and rationally.

The Compact Muon Solenoid, a general-purpose particle physics detector in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Europe (Wikimedia Commons/SimonWaldherr)

We still find the golden thread that is the presence of God's action, whether that's through the movement of the Holy Spirit, and I talk about quantum mechanics as an analogy for how the Spirit works in our lives — "Evolution Jesus" — as this amazing evolutionary singularity. What is amazing to me is the adaptability, the fluidity of our faith that is readily seen in light of the big concepts of science if we look.

One of the most fabulous parts of the book that people might not take the time to know is the cover. The cover is the work of an Indigenous woman in who lives outside Alice Springs in the northwest territory of Australia. These Catholic women were part of a spirituality center there, and they were asked to paint their favorite Bible quote. The cover is Georgina Furber's interpretation of the Annunciation. It looks like the stars, but it is her version of the Annunciation.

This cover is what I hope the book is about, that our understanding of the stars is deeply rooted in our desire to understand, but it also fits well with our sense of Scripture, our sense of theology, our sense of the deeper questions.