Loretto Sr. Jacqueline Grennan, foreground, and Loretto Sr. Francetta Barberis, far right, walk with Conrad N. Hilton to the groundbreaking for the new theater on the campus of Webster University, then Webster College, in 1966. (Courtesy of Webster University)

Allen Carl Larson, a professor emeritus of music at Webster University in St. Louis, has long been engaged with a project to publicize letters between two Sisters of Loretto and Conrad N. Hilton (1887-1979), the founder of the Hilton Hotels and Resorts chain and the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, the primary funder of Global Sisters Report.

The letters center on correspondence that began in 1958 between Hilton and two sisters — Sr. Francetta Barberis and Sr. Jacqueline Grennan — as the women recruit Hilton's help in funding what became the Loretto-Hilton Center for the Performing Arts on the Webster campus, a major arts venue in St. Louis.

Hilton eventually provided $1.5 million of the $1.9 million needed to build the facility, which opened in 1966.

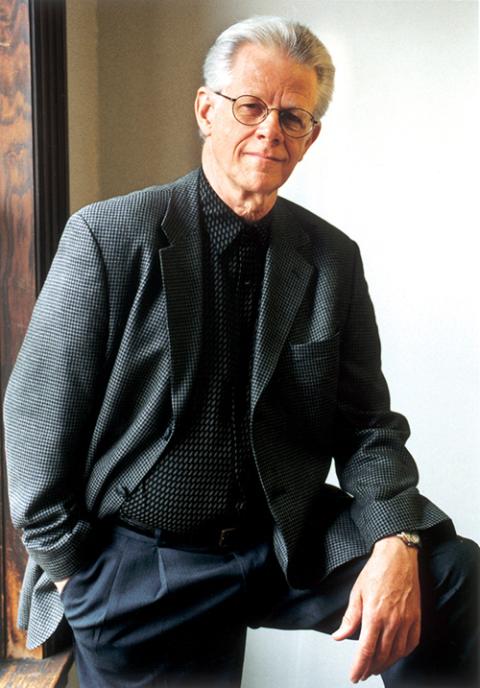

Allen Carl Larson (Courtesy of Webster University)

Larson, whose 36-year career at Webster centered on orchestral and choral conducting, is currently working on a play based on the letters, which were released in 2019 in a self-published book, The Sisters Backstage: A Story of Faith, Perseverance & the Loretto-Hilton Theatre.

Hilton, who grew up in New Mexico, was educated by Loretto sisters and had a lifetime loyalty to the congregation and to the work of Catholic sisters generally.

The letters chronicle the sisters' persistence and Hilton's eventual embrace of the project. The letters are both endearing — from the beginning, Barberis addressed Hilton as "Connie" — and poignant.

In a 1962 exchange, Hilton recalls watching the night sky from his California home and seeing the planet Venus and a crescent moon.

"I watched them for a moment that I said to myself, these two bodies make me think of Sisters Francetta and Jacqueline. You two will have to make a decision as to which one is the crescent and which one is the star," he wrote. He added that seeing the images in the sky made him "think of my loyal and loving allies."

Loretto Sr. Francetta Barberis watches Conrad N. Hilton sign the architect's rendering of the Loretto-Hilton Center for the Performing Arts at the center's 1966 groundbreaking. (Courtesy of Webster University)

Larson came upon the letters by accident. As he and his family moved into their home near the Webster campus in the summer of 1973, Larson found a pile of discarded letters on the sidewalk atop some boxes, apparently thrown out in an office housecleaning.

He began reading the letters and said he was "hooked," sensing that the letters were of historic value.

"I had just read the most compelling and dramatic story," Larson writes in the book, "and was moved beyond any expectation."

Conrad N. Hilton (Courtesy of Webster University)

GSR: You mention this several times in the book: the quality of the writing, which is courtly, like something from a different era.

Larson: You were absolutely right about that. I find that the most interesting part of all these letters is being astounded by the use of language. "I'll certainly do my best and try like you to think big always," things like that. People don't write like this anymore. And I think that this book is as interesting for the style of writing as anything else.

When I tell people that Conrad Hilton had a connection with sisters from an early age, they are always surprised by that. Have you had a similar experience?

Yes. When I was interviewed by public radio back in December 2019, the woman asked, "Everybody thinks Hilton was kind of tight with the money and this and that and didn't know much about the sisters." I said, "Well, no, that's contrary. He was very philanthropic. And he loved the sisters."

Though Sister Francetta's relationship with Hilton began before she was at Webster [as president], the focus of the book is on her attempts to build a fine arts center at Webster. And that's a story itself.

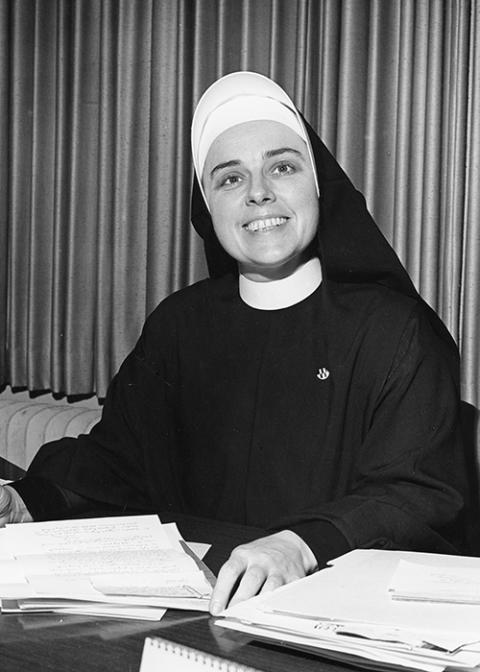

Loretto Sr. Francetta Barberis (Courtesy of Webster University)

One of the things about Sister Francetta and then eventually Sister Jacqueline [who was first vice president for development and then succeeded Barberis as president] is that they just don't give up. Hilton will tell them, "I can't help you this time." He first turned down their request for $1.5 million. And the next letter from Sister Francetta reads, "I respect very much all that you do. And I do understand how many are dependent on your help. Your message to me is completely satisfactory." But then she goes on to say that she is certain he will eventually help her with the fine arts center. She's amazing.

Why was the Loretto-Hilton Center for the Performing Arts so important to the sisters?

The Loretto Sisters are very big in education. That's their main mission. And on this particular campus, there were a couple of other sisters who were pushing to have a better theater and so forth. It was an all-girls school at that time, and they would have to recruit male students from St. Louis University to come over and play the male parts. More people in the city became interested in the theater then — it sort of developed its own excitement. And so, in order to carry that forward, the school decided it needed to have a whole fine arts campus.

How central is the center to the art scene in St. Louis?

It's extremely central. Opera Theatre of St. Louis performs there. They're a major company, as is the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis, one of the most important theater companies in the state. People come to the campus nearly every night of the week to see plays. And then, for the campus, the university has a major theater program. There are a lot of graduates from the theater program working in television now.

Advertisement

Tell me a bit about the play you are writing based on the letters.

There've been a number of plays that are a bit like Thornton Wilder's "Our Town" — basic theater without a lot of dramatic action but with a narrator like "Our Town." I decided to put Sister Jacqueline as the narrator. She comes on the scene, and I have her opening the play with saying, "Look at this wonderful space" into the audience. And then you wonder how it got that way.

Even today, not many people in St. Louis know the Loretto-Hilton connection. In fact, there's a story recently that someone overheard a woman walking through the lobby of the theater, telling other people about the theater. She said, "Well, there's this wonderful woman, Loretto Hilton, who gave money to build a theater."

Loretto Sr. Jacqueline Grennan (Courtesy of Webster University)

What are some of your favorite anecdotes from the letters?

The sisters start asking Hilton for a chance to come and talk to him in person in New York, even briefly. Sister Francetta wrote, "I consider this meeting with you so vital to the future dreams of the Sisters of Loretto, that Sister Jacqueline and I plan to come to your office at 11:30 Saturday in hopes that your busy schedule will permit a short conference."

So sure enough, they arrive in New York, and in the middle of the book, there's a three-page memorandum typed all out about the visit. They finally convince Hilton to take on raising the funds. And so they're suddenly very giddy, and Sister Francetta and Conrad Hilton start dancing around his office to the old song "Put Your Little Foot." That was one of Conrad Hilton's favorite tunes.

Is there much talk about faith in the letters?

All the time. Absolutely all the time. Hilton had supported Sister Francetta at Loretto Academy in El Paso, Texas, [before she was named president at Webster] and in the first letter she wrote in the correspondence, she said, "I want to assure you again of my deep gratitude for your warm personal interest in my work in El Paso, I could have done little there without you. Each day, I asked the good God to shower you with his choicest blessings. May his peace and courage be yours daily. May God be with you at every moment, blessing you and enriching your life with his love and goodness. As you enrich the lives of those you daily contact with your indomitable courage and faith."

As for Conrad Hilton, he was once on the "This is Your Life" program and talked about his faith and Catholic life and things like that.

What was the biggest surprise for you in this correspondence? What jumped out to you in terms of something that was really remarkable?

As I said before, I was surprised by how elegant and clever the writing is — the brilliant use of the language and also the sisters' indomitable spirit, of never taking no for an answer when they're trying to get Conrad Hilton to give money.

The other surprise was about my own reaction. Every time I give a talk about the letters, I can't stop getting all choked up about it. I'm not religious at all, but the spirit with which these people did their work just knocks me out.

I have deep admiration for these women, tough sisters — but tough in a good sense. They do their job. They don't give up. They keep doing what they need to do to support education. The letters tell the story of faith, hope, perseverance and philanthropy. They could also serve as a crash course in fundraising.

What could someone who's in fundraising learn from these letters?

One, show immediate interest in the person they're writing to, and then slowly go into what the needs are and what you are asking for. A lot of people write grants seeking funds, but they kind of forget to ask directly what it is they want, what it's for. Two, always use good grammar, good use of language. And three, be passionate about your cause. Don't downplay what you're seeking the money for.

I had to raise a lot of money during my career for orchestras, for music, for the arts. And a lot of people said my letters were so important because I was told I was passionate about what I wanted and was doing. I think Sister Francetta and Sister Jacqueline were the same way. It was not just business for them. They had a real passion for what they were doing.