Sr. Jane Herb in her office July 19 at the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary motherhouse in Monroe, Michigan. On Aug. 13, Herb will become president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

In her late 20s and early 30s, Jane Herb thought she had no reason to consider religious life. It was the early 1980s; she had a promising career in Catholic education and was having fun coaching sports.

"Why should I give up the life of a single woman?" she asked herself at the time.

Herb was chair of the math department at Regina High School in Harper Woods, a suburb of Detroit, and coached several of the school's sports teams. She thought she had everything she needed in her life.

But she got to know a sister at the school from the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Monroe, Michigan, and began to connect with her. Herb began to want something more in a life she had thought was complete.

"I began realizing that what I was seeing was what I was missing in my life," Herb said.

A picture from Regina High School's 1984 yearbook, when Sr. Jane Herb (top right, on ladder) was chair of the math department. The department members used their initials in an equation to spell out "MATH." (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

So in 1983, at age 33, Herb became an Immaculate Heart of Mary sister, unsure of how she would adapt to living in community.

That was then. Now, Herb will move from being president-elect of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, which represents about 80% of the more than 40,000 sisters in the United States, to being the organization's president on Aug. 13, during LCWR's annual assembly, making her in some ways the face of the country's religious life.

Past-president Sr. Jayne Helmlinger, a Sister of St. Joseph of Orange, California, will end her term in the presidency during the assembly. Current president and Adrian Dominican Sr. Elise García will become past-president, and Sr. Rebecca Ann Gemma of the Dominican Sisters of Springfield, Illinois, will become president-elect.

Because LCWR's triumvirate presidency is collaborative, Herb said she doesn't expect much to change from her time as president-elect except that there may be more speaking engagements, if the pandemic allows.

"The commitment time-wise is probably comparable, but the psychic energy is probably different," she said.

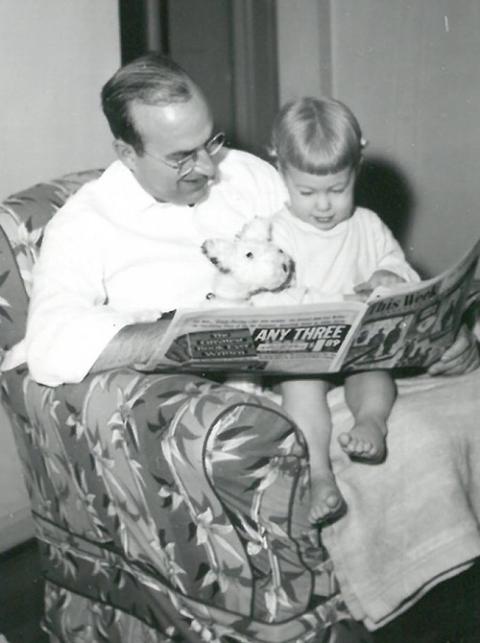

John Herb reads to a 2-year-old Jane. (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

The path to leadership

Mary Jane Herb was born Dec. 10, 1949, to John and Martha Herb and grew up the oldest of four children in the Detroit suburb of Oak Park until the family moved to Plymouth, Michigan, when she was in eighth grade. John was a quiet insurance executive and Martha was an extroverted stay-at-home mom.

"Dad had a quiet sense of leadership, and I think I embody that," Herb said.

She attended Catholic schools run by the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Felix of Cantalice, or Felician Sisters, and stayed busy playing sports, either in the neighborhood or at school, where she was on the basketball and softball teams.

"Softball was my strength," Herb said. "I played basketball, but I was anything other than a star."

Martha's family was from Kentucky, and the family would often visit to see her uncle, John Dickman, who was a diocesan priest in Louisville, and her aunt, Jane Dickman, a member of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, not far away.

Eleven-year-old Jane Herb, far right, poses in 1960 with her siblings, from left, Marge, Paul and Jim (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

After graduating from high school, Herb entered the Felician Sisters in Livonia, Michigan — she was familiar with the Felicians from school and did not even consider other communities.

But it was the late 1960s, and after the Second Vatican Council, a new vision of religious life was forming. Like many congregations, the Felicians were not rushing to embrace that vision, and in 1970, after two years, Herb left.

"It just wasn't the right fit," she says.

She earned her bachelor's degree in education from the Felicians' Madonna College in 1972 and a master's degree in education from Wayne State University in 1978, and she enjoyed teaching and coaching.

But at a directed retreat, she realized that while she may have said "not here" or "not yet" to religious life in 1970, she had never said "no." And she realized she wanted something more.

What she wanted — and what God was calling her to — was the charism of the Immaculate Heart of Mary sisters.

While her parents had supported her decision to join the Felicians, her mother wasn't so sure about such a big change 15 years later.

"Mom was a bit hesitant," Herb said. "She was saying, 'Why are you doing this? You have a good job. ... Why would someone in their early 30s change their lifestyle?' "

Adapting to community living wasn't easy, but she continued to coach sports so the transition didn't seem so abrupt.

"It was a wonderful formative community," she said. "I really loved what community life was like."

Sr. Jane Herb, second from left, celebrates the jubilee of her aunt, Sr. Jane Dickman of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, Kentucky (far right), with her uncle Fr. John Dickman and her mother, Martha Herb, in 1993. (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Nancy Sylvester met Herb when Herb entered the community but really got to know her when Sylvester was elected to congregational leadership in 1994.

Decades of declining membership meant sisters were no longer in the classrooms the congregation had founded or on the frontlines in many of its sponsored ministries. An important question was arising: What exactly was the relationship of the congregation to a sponsored ministry if there were few or no sisters working there? And how would that ministry carry on the congregation's charism?

At that time, Herb was working on a doctorate in education from Boston College, and her dissertation was "An Investigation of the Role of a Religious Congregation, as Founder, in the Shaping of School Culture of a Secondary School." She began to work with Sylvester to find ways to ensure the charism of the sisters remained in their ministries, even when sisters were not there.

"We worked together on that several years," said Sylvester, the founder and executive director of the Institute for Communal Contemplation and Dialogue and a former LCWR president.

Herb said that work continues for congregations nationwide who are spinning off ministries or handing them off to partners.

"It's finding common grounds," Herb said. "It's about how we address social ills, and vowed religious don't have the corner on that market."

Sr. Jane Herb, right, with her mother, Martha, after Jane graduated with her doctorate from Boston College in 1997 (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

After getting her doctorate in 1997, Herb became superintendent of schools for the Diocese of Albany, New York, and continued in the position until she was elected to her congregation's leadership in 2012.

Thomas Fitzgerald, her assistant superintendent from 1997 to 2006, said while Herb's administrative skills are considerable, "she is more a leader than an administrator. In my mind, she expertly manages paper and manages people, but she's also a leader with a vision for the future."

A key to her success, he said, is building relationships. She was the only Immaculate Heart of Mary sister in the Albany Diocese, but he said she immediately began forming bonds with all the local religious congregations and began to change how the Catholic schools in the diocese interacted with the central office.

"Before she came, the Catholic Schools Office was seen by schools as only getting involved when there was a crisis or when you did something wrong," Fitzgerald said. "There were 42 schools, but they did not see themselves as part of a system of schools, which they really are."

Fitzgerald said he and Herb began to drop in on diocesan schools unannounced to build better connections.

Sr. Jane Herb reads to a class in 1998, when she was the superintendent of Catholic schools in the Diocese of Albany, New York. (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

"The principal would be concerned: 'What did I do wrong?' And I'd say, 'I just want a cup of coffee.' It became a standing joke," he said.

"If you looked at the Albany Catholic schools, it was a changing of the culture for the better through Sister Jane. It became a culture of support and Catholic identity."

Those relationships also helped when hard decisions had to be made. At that time, most schools were "a year or two away from a fiscal crisis," Fitzgerald said. Herb included each school in strategic planning and decisions, so when schools had to be reconfigured or closed, the decision was not entirely a top-down decision from the central office.

"She had a collaborative approach. She involved people," he said.

Sr. Jane Herb meets Pope Francis in 2013, when she was a delegate for the International Union of Superiors General. (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

In leadership, an emphasis on collaboration

Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Marianne Gaynor said Herb brought that collaborative approach to congregational leadership. Gaynor joined the leadership team in 2018, at the start of Herb's second term as president, but has known her since Herb joined the community in 1983.

"What she tries to do is listen, to take the experience she has and what's happening and see how it all fits together," Gaynor said.

Herb is also not shy about addressing problems.

"She doesn't let things simmer too long," Gaynor said. "If there's something she needs to address, she usually addresses it pretty directly. But she tries to hear both sides, basically saying, 'Where are we going with this?' "

Herb prefers order and predictability but soon learned that congregational leadership required more flexibility.

"Living with ambiguity is not my strong suit," Herb said. "The pandemic brought out [facing the unknown] in so many ways. One day, everything's operating normally, and the next day, you're shutting everything down."

Sr. Jane Herb shows off her Ruth Bader Ginsberg mask July 19 in her office at the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary motherhouse in Monroe, Michigan. On Aug. 13, Herb will become president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

Before the pandemic, Gaynor said Herb made it a point to personally visit each of the congregation's missions, a job usually left to the mission councilors.

"I felt it was important" to not only see things firsthand, but for the sisters to know the entire congregation was behind them, Herb said.

Sylvester also noted Herb's pastoral skills, recounting how, during months of lockdown at the motherhouse, Herb visited the older sisters who could not have visitors from outside and arranged social gatherings via Zoom for those now locked out of the motherhouse.

"You need to know yourself, " Sylvester said. "Administration is different than being a leader. A leader needs to know what she does well and what you need help with, and Jane does."

Herb said it's just a matter of recognizing others have much to bring to the table — it only makes sense to rely on their expertise.

Her collaboration skills also turned one potential disaster into an example of creative partnership. When the order's Marygrove College in Detroit closed in 2019, Herb helped bring together partners, including the Kresge Foundation, to turn the campus into a cradle-to-career education conservancy, which is now home to an early childhood education center, a public K-8 school and high school, a University of Michigan School of Education teaching residency program, and several arts and culture groups.

"It would have been a great loss had this property been become another empty lot," said Sylvester, who lives on the campus. "Instead, it is a hive of activity."

It is providential that Herb is in the LCWR presidency at this particular time, Sylvester said, as religious life faces questions of how to address racism and its own future.

Advertisement

The Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Monroe as well as the Immaculate Heart of Mary congregations in Scranton and Immaculata, Pennsylvania, all mostly white, have been working for more than 25 years to address their own history of racism and chart a new path forward with the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the first congregation of Black women religious in the United States, with whom they share a foundress.

Theresa Maxis Duchemin, who was biracial, co-founded the Oblates and then went on to found the three Immaculate Heart of Mary congregations but was scrubbed from the white congregations' histories. Since 1995, the four communities have been working on racial healing and have formed a joint governing board, of which Herb is a member, to oversee the partnership.

That experience will help as LCWR and its member congregations examine their own racism and work through how to address racism in society, Sylvester said, noting that Herb is "able to be very sensitive to it and see the implications of it."

And Herb's strategic planning skills will help as LCWR discerns its own future as an organization and the future of religious life in general in the United States.

"Not everybody can see the whole picture," Gaynor said. "Some of us see the detail. Others can see how it all fits together, and Jane can do that."

Sr. Jane Herb in her office July 19, 2021, at the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary motherhouse in Monroe, Michigan (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

Seeing the big picture is also part of Herb's spirituality, Gaynor said.

"The importance of the IHM mission and the importance of the mission of religious life in general — she's so convinced that that's where the strategic planning and the spirituality bump up together," Gaynor said.

Herb says faith is critical in that respect; it is frightening to go into the unknown.

"Nobody's going to tell us the future of religious life. To me, it's about creating these conversations not knowing what's around the corner. It's the Spirit working," Herb said. "We're not in charge, but we've got to find a way through it."

Sr. Jane Herb, left, hikes in Utah with Sr. Nancy Sylvester, also a member of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, in 2018. (Courtesy of Jane Herb)

After Herb joined the Immaculate Heart of Mary community, the rigors of religious life meant she had to give up the intramural sports she loved to play, especially softball. Now, she hikes, goes on bike rides, and camps whenever she can.

"To be out in nature really refreshes my soul," Herb said. "I love to tent camp, but I haven't been able to in a few years. A friend told me, 'You're a different person when you're out here [camping],' and I think that's true."

Sylvester is not a camper, but she loves to camp with Herb.

"We have a great time and laugh ourselves silly," Sylvester said. "You don't often have an opportunity for that."

And Herb appreciates the time in nature, where she can relax and change her focus.

"You can't be in leadership if you want it to be boring and routine," she said.