Sisters of Mercy of Burlingame, California, pose for a photo early in the pandemic as part of their congregation's campaign to get migrants out of detention, where they are especially vulnerable to COVID-19. (Courtesy of Sr. Deborah Watson)

Editor's note: On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization said COVID-19 could be characterized as a pandemic. One year later, millions of lives have been lost to the virus, and people worldwide are taking stock of the last year and what the future holds. This week, Global Sisters Report looks at the impact of the pandemic on religious life with a special series, Coronavirus: One Year Later.

(NCR, GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Although she's lived alone for the last five years, this past year has been a creative and spiritual challenge for Sr. Patricia Soltesz, who has been finding ways to fend off isolation and foster some sense of community as the coronavirus pandemic continues to keep her apart from most of her sisters.

Before, she'd regularly volunteer at her Immaculate Heart of Mary motherhouse in Monroe, Michigan, about 40 minutes from her apartment outside Detroit, visiting her friends in the assisted-living area and helping however she was needed: setting up the dining room or bringing a Honeycrisp apple to one sister who loves them.

"If I'm able to give myself to people, it's like I have a purpose," she said.

But now, in addition to feeling lonely, she's started to wonder what purpose she can serve from her apartment. Aside from running errands, seeing the doctor, or passing people in her building's hallways, "it's been a whole year since I've physically seen people."

Community life — living, praying, celebrating, sharing meals, or simply gathering together — is a powerful draw to the religious vocation (cited alongside spirituality, charism and mission). Fellow sisters become one's immediate family and support system. For most congregations, eremitical life notwithstanding, community life is integral to religious life.

A robust sense of community, once a constant, is now a luxury, if not a health risk. That's left sisters like Soltesz, who live alone or are otherwise removed from their congregations, to spend the year finding new outlets for deeper connection.

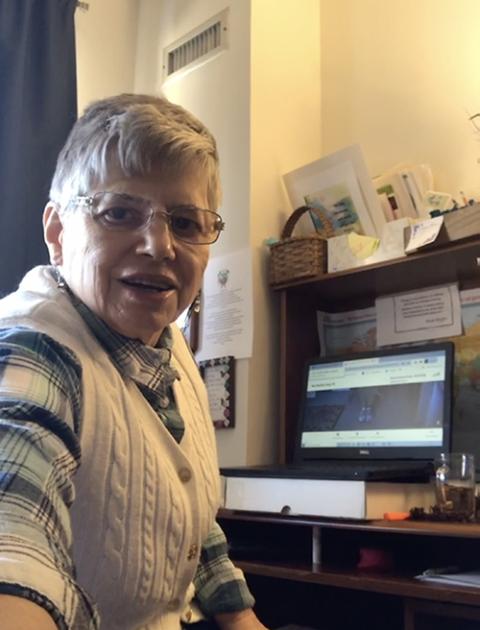

Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Patricia Soltesz takes a selfie during an online exercise class, one of the many ways she's maintained a sense of human connection while living alone. (Courtesy of Sr. Patricia Soltesz)

Soltesz, 78, also used to have that steady sense of community in her apartment building, but the pandemic has put an end to their regular parties and interactions, too — "another form of my community that I'm missing," she said. "I've felt lonely and isolated."

Online group prayers have helped her maintain a sense of connection with her fellow sisters. She also signed up for various online programs offered through local universities, including a senior wellness program, group exercise classes, and lifelong learning sessions, all in addition to the regular Zoom calls and prayers she has with her congregation.

Learning how to be a "community person wherever I am," regardless of geography and physical company has "expanded" her concept of community, she said.

Even though Sr. Carol Ann Petersen of the Mount St. Scholastica community in Atchison, Kansas, is the liaison between her Benedictine sisters and the rest of society, she has spent the past year completely cut off from the rest of her congregation: She has the monastery's third floor all to herself. With about 30 sisters in the building's nursing facility, which is connected to the rest of the monastery of 70 sisters, playing it safe with the virus was paramount.

Petersen, 76, volunteered to self-isolate between the many errands she runs for her sisters first thing in the morning before places get busy: daily trips to Walmart; regular visits to the post office, bank, library and pharmacy; and picking up takeout orders to support local restaurants. She leaves the food on a common table so she can avoid contact with sisters altogether.

Though she never imagined this arrangement would last a year, she chose to continue serving in this role even when her prioress said Petersen could switch with someone else.

"Emotionally, I can do it," she said, noting that being an introvert has made her isolation relatively bearable. "I really have enjoyed giving service to the community. It's been a kind of gift to be able to do this for them, like an extended retreat."

Between errands, Petersen also continues the community's ministries, visiting women in the local jail on her sisters' behalf, taking meals to people experiencing homelessness, and donating items to Catholic Charities or other agencies. Throughout the pandemic, she said, "I've been proud of our community for focusing on the needs for our larger community, not just ourselves."

Advertisement

While she misses participating in daily prayer and singing with the sisters in person, Petersen said being able to livestream those activities and stay in touch with her sisters, friends and family over Zoom keeps her from feeling truly disconnected.

"I'm making an effort every day to be grateful," she said. "I know our community has been blessed. I know I've been blessed. That's the one thing through the year that I've been very aware: this great feeling of gratitude that we're all safe, that we've been able to do what we need to do to keep each other safe."

Though all the sisters in the monastery are now fully vaccinated, Petersen said they will be slow to loosen their restrictions to ensure the sisters in the nursing home remain safe.

"Knowing there are so many people who are isolated, especially seniors, older people — [I'm] really trying to join in spirit with them," she said. "I try consciously every day to pray for people that are having a hard time doing this because they didn't have a choice."

Far from home

Though Sr. Deborah Watson, 77, isn't experiencing isolation while staying at her Sisters of Mercy motherhouse in Burlingame, California, she's about 6,500 miles away from where she'd like to be: her home in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Watson, who works in communications for her congregation's Caribbean, Central American and South American institute, was visiting family and friends in Burlingame after a work trip in Jamaica when travel restrictions following the onset of the pandemic kept her in the United States.

Mercy Sr. Deborah Watson, left, with Haifaa Danora, a Syrian refugee she accompanies in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Courtesy of Sr. Deborah Watson)

Since October, Watson has been able to return to Argentina, but she has been hesitant to try, fearing the possibility of arriving in Buenos Aires to find she is missing some paperwork or "a hoop to jump through." (She is now fully vaccinated and plans to return to Argentina in May.)

While her communications work can be done remotely, she's missing out on her ministry accompanying a Syrian refugee family — a couple and their two teenage sons — with a team from Manos Abiertas, a Jesuit-sponsored set of ministry projects that serves people in need, including refugees. In addition to helping the family with paperwork regarding health care, education, social services and financial aid, Watson also supports the mother as she learns Spanish and works to establish a small business selling Arab food from her kitchen.

Though Watson is still connected with them through WhatsApp, "it is obviously not the same."

She has spent the last 35 years ministering either in Peru or Argentina and said she is now unaccustomed to spending so much time in the United States, where materialism and commercialism are rampant.

"I have a real sense of being in an ivory tower here," she said.

"There are wonderful ministries going on from the Mercy Center in Burlingame — no doubt about that — but it's a whole different perspective," she said. "We see things from where we stand. ... Living with the option to be with the most marginated, even if you're not serving them directly, you're encountering them."

Although she's always considered California her home, Watson said, "being here has strengthened my desire to return."

Smaller community within the community

In Los Angeles, roughly 40 minutes away from the Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange motherhouse, a small group of sisters has begun to deepen their own communities within the larger community: an informal "regional group" of nine Sisters of St. Joseph who live in the same area and a smaller group of five within that group who live together.

From left: St. Joseph Srs. Mary Beth Ingham, Sara Tarango, Joanna Carroll and Clara Dong relax in the community room of their Los Angeles home in August 2020. Since the start of the pandemic, Ingham said dinner with her housemates has gone from sitting around a table to sitting in socially distant, comfortable seats in the community room, which inadvertently leads to longer, more relaxed conversations. (Courtesy of Sr. Mary Beth Ingham)

"We see ourselves as our own little pod," said St. Joseph Sr. Mary Beth Ingham.

Because most of the sisters' ministerial activity happens over Zoom, being home all the time has created "its own community experience of a deeper intimacy just by virtue of the fact that we're physically around each other all the time," she said.

Since the start of the pandemic, she has noticed their new tendency to linger longer after dinner now that they sit farther apart in comfortable chairs to maintain social distance as they eat.

"We lose the physical intimacy of the dining room table, and yet we gain a deeper intimacy by sitting longer, talking longer about our day," she said. "It's a subtle shift" — and a tweak she said she imagines they will maintain even after the end of the pandemic.

Srs. Sara Tarango and Clara Dong cut a cake celebrating their entrance into the novitiate of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange, California. They could not celebrate with the community at large because of the pandemic, so their housemates threw them a smaller party. (Courtesy of Sr. Mary Beth Ingham)

Ingham recalled the disappointment she and her sisters felt when one of their housemates made first vows in spring and first profession in September while the rest of them watched on Zoom rather than attend in person.

"On the other side of that, we pulled out all the stops for them and had a bigger celebration for her out here than we probably would have had if we went to Orange," she said, adding that the same happened when the two novices she lives with entered the community.

"We've accommodated the disappointments of not being able to be with the larger congregation by making our smaller congregational setting out here even more important."

Making the best of their situation has also bonded the sisters. Ingham said Christmas was "particularly poignant" for their new members who were unable to be with their families. In this moment, she saw how their group has "grown in our depth of sharing," she said, particularly in their willingness to be "more open with each other about the difficult times and the periods where you do want extra help or patience."

Mercy Sr. Mary Sullivan has found herself living alone since her housemate had to move out temporarily following an injury in January this year. Still, she said she hasn't felt lonely, and her life in Rochester, New York, hasn't changed too much throughout COVID-19. But her concept of "togetherness" has.

Sullivan, 89, said she believes the pandemic, "with all its isolating features, has been calling all of us to reshape our hearts."

Mercy Sr. Mary Sullivan (Courtesy of Sr. Mary Sullivan)

"This is a sacramental moment in which we can allow ourselves to be transformed, and in that sense, it is an especially blessed time," she said, calling it a "kairos moment" in which the "spirit of God is teaching us not just how to live through isolation and fear of the disease, but how to widen our neighborly love."

Every evening, when she sits down to eat, Sullivan's mind goes to the suffering of those in Yemen, those on the U.S.-Mexico border, those on the city streets, she said.

"Rather than feeling alone in the pandemic, I have come to feel more connected with the whole human family and what they are enduring. It's a time of humble awareness of our constant dependence on God's mercy and on the help of one another.

"You hear people say all the time that we're in this together, that togetherness is a new and deeper understanding that is being offered to us by the pandemic."