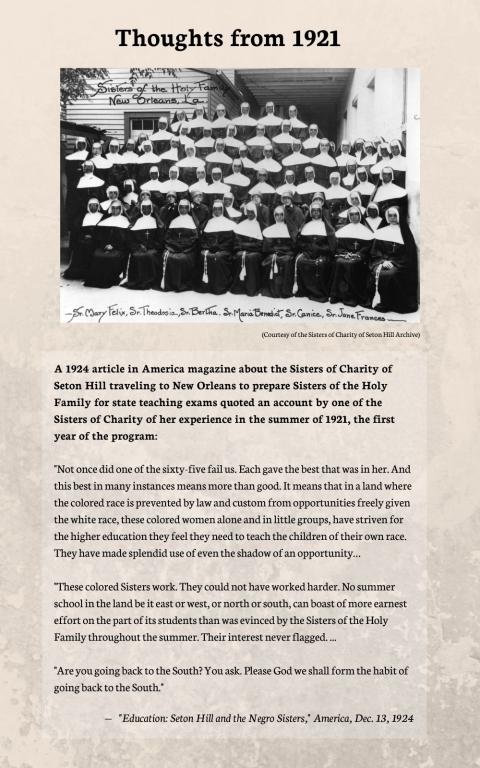

Sisters of the Holy Family, in the white-and-black veils, and Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill, in the black caps, in New Orleans in the 1920s (Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill)

In the 1960s, Sr. Sylvia Thibodeaux moved away from her Black congregation, the Sisters of the Holy Family in majority-Black New Orleans, to attend mostly white Seton Hill University, run by the white Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill in the almost entirely white city of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, about an hour east of Pittsburgh.

"I was a young woman, and I had never been away when I left home to enter the convent. I had never been away from my parents or out of the immediate area," Thibodeaux said. "So coming to the Pittsburgh area was a real experience for me."

It was an experience that many sisters from both congregations have shared for decades in a relationship between the two communities that has stayed strong, despite distance and cultural divides, for 99 years.

"One of my teachers, Sr. Gemma Marie [Del Duca], we became friends," Thibodeaux, now 84, said. "We're friends today. ... She wants me to go to Israel with her. Can you imagine?"

The start of a spiritual bond

In 1921, the Sisters of the Holy Family were in a bind: They were primarily teachers, and the state of Louisiana had begun requiring certification. But the sisters couldn't take the classes required for certification because schools were segregated, and Blacks were not allowed.

A call for help went out to women religious in the North, and the Sisters of Charity responded, sending six sisters from Seton Hill to New Orleans to teach summer classes. The Sisters of Charity's own college had been granted its charter as a four-year institution only three years earlier, but the sisters designed a curriculum and got to work. Four summers later, 10 Holy Family sisters passed the Louisiana state teachers exam and were certified.

Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill, in black veils in the back, teach Sisters of the Holy Family to prepare them for the Louisiana state teaching exams in the 1920s. (Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill)

"The [Seton Hill] sisters had not been in existence that long when they responded to the call," Thibodeaux said. "How generous they were to have done that. ... They didn't think about it. They immediately responded to a need, and at great risk because of the violence and racism that existed in our region."

Then the state began requiring college courses for certification, and the Sisters of the Holy Family faced the same problem, as they were barred from colleges in the South. Eventually, the sisters were able to enroll at Xavier University in New Orleans, and the Seton Hill sisters changed their summer classes to college-prep courses to prepare the sisters for their university careers.

That partnership, where white sisters from the North went south to help their Black counterparts, continued for more than 30 years, until civil rights laws allowed the Sisters of the Holy Family to open their own junior college in 1957.

"Our interest in your beloved Community will never change," Sisters of Charity Mother Claudia Glenn wrote to Holy Family Mother Mary Philip Goodman as that phase of their partnership ended, according to Celebration, the Seton Hill magazine.

Goodman replied, "We know this mutual relationship will not be severed."

A telegram from the Sisters of the Holy Family to the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill on July 19, 1958, then the feast day of St. Vincent de Paul. The summer of 1958 was the first summer since 1921 that the Sisters of Charity, who trace their roots to St. Vincent, were not in New Orleans to prepare Sisters of the Holy Family for state teaching requirements. (Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill)

One reason it has remained intact is the relationship has never been one-way. In 1942, to mark the Sisters of the Holy Family's 100th anniversary, Glenn established a pair of scholarships for Holy Family sisters to attend Seton Hill, a program that continued until 1976. The first Black woman to graduate from Seton Hill was a Sister of the Holy Family.

Thibodeaux was a scholarship recipient, graduating from Seton Hill in 1967. One of her English teachers there had been in that first group of six Sisters of Charity to go to New Orleans.

"They were women of great courage and generosity," she said.

In the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the two communities conspired to bring integration to their schools and established a faculty exchange program, trading teachers so Black sisters would teach white students in the North and white sisters would teach Black students in the South. The program, which ran from 1967 to 1979, let the teachers experience life in a culture other than their own and gave the schools much-needed diversity.

Advertisement

The personal and spiritual relationship remains strong today.

Del Duca, 88, said the reason is as simple as it is profound: "I think we like each other."

Though Del Duca and Thibodeaux don't get to see each other often, and each says they should probably stay in touch more, the bond remains.

"There's a love for one another," Del Duca said. "When we sit down together, we can pick up immediately on the issues of social justice. I think that's created a strong bond between us. We trust each other, that whatever cause or issue is out there, we can help each other find some insight. I think it creates a strong spiritual bond between us."

Different realities, similar people

Charity Sr. Miriam Richard Soisson was in the first group of teachers in the exchange program. She not only found herself in a different culture, but she saw the realities of the Jim Crow South in person.

Three Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill pose with Sisters of the Holy Family at the Holy Family school where they taught in New Orleans in 1969. The three Sisters of Charity were part of a faculty exchange between the two orders, sending white sisters south to teach in Black schools and Black sisters north to teach in white schools. (Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill)

It was 1967. By then, Soisson and the other Seton Hill sisters were able to live at the convent with the Holy Family sisters, she said; previously, it would have been illegal for whites and Blacks to live together. One of the Holy Family school's kindergarten teachers had tried to rent a house near the school but was rejected because the owner wouldn't rent to Blacks. Bystanders stared when Soisson rode in the car with her principal, wondering what a white woman and Black woman were doing together.

Soisson and another Seton Hill sister were the only white people at the school where they taught. At church, the two sisters and the priest were the only white people at Mass.

"It made you become more conscious both with the students and the faculty. They had the same desires, the same goals as us," Soisson said. "It's all the same."

Charity Sr. Vivien Linkhauer was a student at Seton Hill at the same time as Thibodeaux, and the two became friends. In the 2000s, Thibodeaux was superior of the Sisters of the Holy Family, and Linkhauer was provincial superior of her congregation.

Thibodeaux wanted to repay the Seton Hill sisters in some way for their support over the decades, so when Holy Family Sr. Alicia Costa earned her doctorate in educational leadership from the University of New Orleans in 2002, Thibodeaux asked her to teach at Seton Hill for two years as a gift from the Sisters of the Holy Family to the Sisters of Charity.

"I was delighted," Linkhauer said. "I knew of the long history, and sisters would often tell stories of their adventures down there."

One story was of a Sister of Charity who got on a New Orleans streetcar when segregation was still the law and sat with her Holy Family sisters in the back. The driver told her she had to sit in the "whites only" section in the front.

"You people are crazy," the white sister replied, and she stayed where she was.

Costa, then 52, arrived at Seton Hill in 2004 and lived with the Sisters of Charity. Just as her white counterparts had learned in the South that everyone is the same, Costa learned it in the North.

"When I lived with them, I could almost pick one for one, the different types of personalities in the congregation that matched," Costa said. "Their skin color was different, but their personality and temperament were the same. Even the build was the same. It's probably true in every congregation."

Another thing was similar: the racism in society.

"I went up to Pennsylvania, and they think they're so advanced, so much more civilized, but I didn't see much difference," Costa said. "The racism is a little more subtle there, where in the South, everything's out in the open. Other than that, it was the same."

Just after Costa returned to Seton Hill for her second year, Hurricane Katrina hit. New Orleans was devastated, and the Sisters of the Holy Family were no exception: Their school and day care were destroyed, their nursing home was nearly destroyed, and the motherhouse had 5 feet of water in it.

Holy Family Sr. Alicia Costa, second from right, sings with Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill during her time teaching at Seton Hill University, where she taught from 2004 to 2009. (Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill)

Costa wanted to return to New Orleans, but the Holy Family sisters were scattered in convents and homes across the state, so Thibodeaux told her to stay. But Costa couldn't just sit 1,000 miles away and do nothing. She got to work, spending much of the next year helping her community by organizing relief efforts.

Costa started raising money and organizing donation drives. Seton Hill University sent Thibodeaux a cellphone with a Pennsylvania area code — phones didn't work in the entire 504 area code — and covered the monthly bills. One of the Sisters of Charity's schools in the Pittsburgh area collected instruments to provide replacements for the marching band at the Holy Family sisters' school. Between the Sisters of Charity and other donations, Costa raised about $250,000 for her congregation.

"It was real support," Thibodeaux said. "They were praying for us. The sisters were really a prayer support as well as helping with material things."

Charity Sr. Louise Grundish said the experience made the relationship even closer.

"That kind of renewed our relationship with the Holy Family sisters," Grundish said. "Since then, I've been back and forth to New Orleans many times. In fact, I lived through another hurricane with them" — Hurricane Gustav in 2008.

And the Charity sisters learned from Costa, including the New Orleans tradition of the "second line," where a crowd joins an in-process parade.

"Vivian celebrated a jubilee at that time, and it was a big celebration but pretty staid, as they all are," Grundish said. "Then Alicia got up with her napkin, started waving it around, and the next thing you know, we're all doing the second line."

Costa was supposed to be at Seton Hill for two years. She stayed five.

"It was a wonderful time," she said. "It was a wonderful experience for me, and I think also for them."

But it wasn't perfect.

"It was freezing-cold weather. I'm not used to that," she said. "Beautiful snow, beautiful fall colors, but that cold was too much."

'We are family'

Age has made travel more difficult these days, but they get together whenever they can.

"We have just been connected from the hip," Costa said. "It has always been this relationship that's existed."

Several Seton Hill sisters traveled to New Orleans in 2017 for the 175th anniversary of the Sisters of the Holy Family; the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill are celebrating their 150th anniversary this year. They exchange Christmas cards and stay together whenever possible.

From left: Charity Sr. Miriam Richard Soisson, Holy Family Sr. Sylvia Thibodeaux, Charity Sr. Louise Grundish, Charity Sr. Vivien Linkhauer and Holy Family Sr. Alicia Costa celebrate the 175th anniversary of the founding of the Sisters of the Holy Family in 2017. Soisson, Grundish and Linkhauer traveled to New Orleans for the celebration. (Courtesy of the Sisters of the Holy Family)

When Seton Hill communications director Jane Strittmatter met the late Sr. Eva Regina Martin, then the Holy Family superior, at a conference in 2011, the sister exclaimed, "We are family!" and sent her home with so many jars of hot pepper jelly she had to check her luggage.

As the United States faces a national reckoning with systemic racism, Casey Bowser, Seton Hill's archivist, said the sisters' relationship stands out.

"For me, this is one of the high points in the church's history," she said. "The Sisters of Charity made a really brave choice, but the Sisters of the Holy Family were the legs in this table. They were pushing Catholicism forward for young people throughout the United States."

Del Duca, who remembers only one Black student at school and the novelty of a young Black woman coming to her house to practice for a recital, said close, individual relationships across racial lines make it harder to judge people as a group.

"If you know someone well and love them, you see it somewhat differently," she said.

Costa said that the vows the orders' superiors made in 1958, that their relationship will not be severed, still stand.

"We've just had this relationship that is really wonderful," she said. "We are sisters and friends, definitely."

Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill and Sisters of the Holy Family in New Orleans in the 1930s (Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill)

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]