Foreground: "Portrait of a Pharmacist Nun," by Stefano Gherardini, 1723 (Szépművészeti Múzeum/Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 2020). Background: A nun works in the pharmacy at Misericordia Hospital (now called Mercy Philadelphia), which opened in 1918, the summer before the worst of the flu epidemic (Catholic Historical Research Center, Archdiocese of Philadelphia).

"I was always fascinated by the stories," said Sr. Patricia Talone, recalling 1918 flu epidemic tales she heard from older sisters when she entered the Sisters of Mercy community in Merion, Pennsylvania, 60 years ago. It was a history that had touched her own family.

From plague to cholera to influenza, past epidemics were opportunities for nuns to serve society beyond their convents in force. Though sisters, like this community health nurse, still serve in multiple roles in health care, they no longer have the numbers to be the recognized face of compassionate care in the current pandemic.

The role of sisters in nursing the victims of the 1918 pandemic that yielded millions of deaths worldwide is increasingly recognized and lauded. What's perhaps less known is that, for centuries, nuns both in Europe and as immigrants to the United States have been ahead of their time, bringing volunteering fervor and entrepreneurial skill to their mission of tending the sick and preventing illnesses from spreading.

Take the clever, well-educated nuns of Renaissance Italy, for example.

These women, often cloistered in a life they had not chosen, "ran commercial pharmacies out of the convent that supplied a considerably big revenue stream for the communities," said Sharon Strocchia, a professor of history at Emory University and author of Forgotten Healers: Women and the Pursuit of Health in Late Renaissance Italy (Harvard University Press, 2019).

A portrait believed to be Maria Celeste Galilei, a Poor Clare nun and illegitimate daughter of astronomer Galileo. She was an apothecary who created remedies for her father. (Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Images)

"The evidence is overwhelming that religious women were deeply immersed in commercial culture and applied remedies that were considered extremely valuable," said Strocchia.

Educated in the medicinal arts of their day, many nuns (among others during that time period) carved out a market niche for themselves by creating specialty remedies, she said. That includes medication to ward off plagues. "One of the smart things that consumers could do was to stock up on preventative remedies when they know that a plague is in the immediate vicinity."

One notable example was the astronomer Galileo's illegitimate daughter, a Poor Clare nun and a well-known apothecary in her own right.

Maria Celeste Galilei created a remedy to prevent the plague for her own father. She advised a mixture of dried figs, nuts and the herb rue, bound together with honey in a portion approximately the size of a walnut, followed by some good wine, reported Strocchia.

As sisters launched orders and congregations and engaged the population outside convent walls, nursing and volunteering really came into their own with the rise of active orders like the Daughters of Charity, founded in the 17th century by Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac. These communities and others founded in the 18th and 19th centuries, like the Sisters of Mercy, saw it as a fundamental part of their call to care for both the poor and the sick.

Members of orders that came over from Europe to North America were often already engaged in ministering to the sick, said Margaret Susan Thompson, a professor at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. "Most of the sisters who came here were really devoted to meeting the needs of the time, and this was one of the needs of the time."

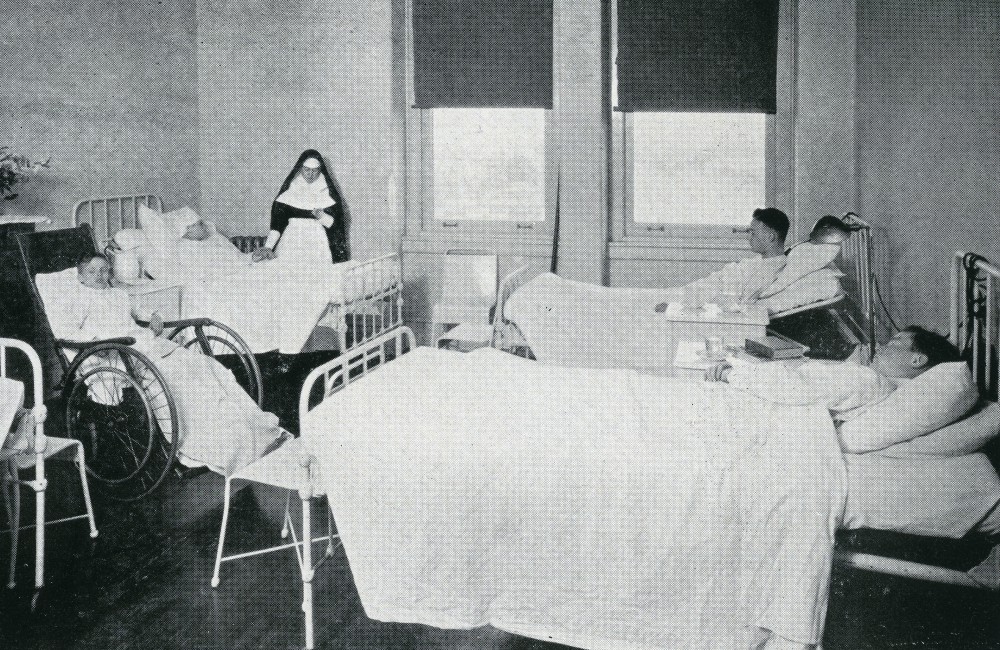

A Sister of Mercy attends patients in a ward at Misericordia Hospital opened in 1918, just before the worst of the flu outbreak. (Catholic Historical Research Center, Archdiocese of Philadelphia)

Even cloistered or semicloistered orders would pitch in when requested. That was true of the Ursulines of the Roman Union.

Upon their arrival in what is now Louisiana in 1727, they were asked to staff a military hospital in New Orleans. There they tended not only to soldiers affected by both war and disease, but to orphans whose parents had died from the diseases rife in that period, according to research done in the Ursuline Central Province archives by Sr. Thomas More Daly and Sr. Sue Anne Cole.

In August, during the cholera epidemic of 1832, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, an African American community in Baltimore, were asked to nurse residents at a local almshouse, according to a contemporary account written by Oblates co-founder Fr. James Hector Joubert, Society of the Priests of St. Sulpice.

Joubert asked the women if four of them would be "disposed to sacrifice themselves to this good work." All 11 stood up, he recalled, "and filled with joy and happiness, they all cried that they were ready to undertake it."

Of the four who went, one even took her vows early — so that if she died of contagion, it would be as an Oblate Sister of Providence. All four returned in good health, said Oblate archivist Sharon Knecht.

But a few months later, one of the four, Sr. Anthony Duchemin, who had nursed the local archbishop through his bout with cholera, fell ill and died suddenly after returning to the house to nurse the archbishop's housekeeper. Her daughter, Sr. Theresa Duchemin, was not allowed to visit her mother for fear she too would fall ill, wrote Knecht in an email.

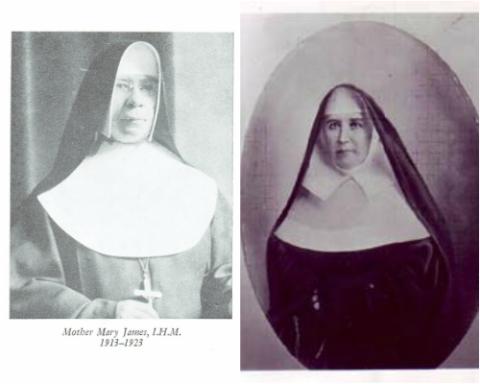

Left: Sr. Mary James Sweeney was mother general of the Immaculata, Pennsylvania, branch of the Immaculate Heart of Mary sisters, 1913-23, leading them through the period of the flu epidemic. Right: Born in Ireland, Sister of Mercy Mother Mary Baptist Russell traveled to San Francisco in 1854, where she nursed the sick through cholera epidemics and founded the first Catholic hospital on the West Coast. (Provided photos)

Innovators in social equality

Nuns did not seem to be daunted, either by geography or bigotry.

Sister of Mercy Mother Mary Baptist Russell already had experience as a crisis nurse during an Irish cholera epidemic when she sailed for San Francisco in 1854, an era of anti-Catholic and anti-Irish bias, said Talone. In 1855, when a cholera epidemic broke out, she added, "the rich escaped the city, but the nuns stayed and nursed the sick and dying. Then the public attitude toward them changed radically."

Nuns were also prominent caregivers during the Civil War, in which soldiers' encampments could become the site of epidemic diseases like typhus and malaria. (Two-thirds of the deaths during that conflict were caused by illnesses like dysentery, typhoid and tuberculosis.) Of the 20,000 women who volunteered to help treat soldiers, approximately 500 were nuns, said Barbra Mann Wall, a nursing professor at the University of Virginia.

Most Catholic hospitals were started after the Civil War by women religious, she said, a circumstance that turned them into "unlikely entrepreneurs."

"When epidemics hit, it was a crisis situation, and they just did it," said Mann Wall. "The nuns would volunteer, making a name for themselves and becoming the image of the Catholic Church."

Epidemic over, she said, sisters would return to their prior ministries, whether in the field of health care or not.

Advertisement

In fact, said Thompson, Civil War nurses were mostly drawn from the ranks of teaching rather than nursing orders. "That volunteering helps them with their spiritual mission: to take care of the poor, of the sick, of the least of these."

Whether in education or health care, she said, sisters didn't limit their ministries to Catholics. "They defined Catholicism for most Americans."

Lessons from a century ago

That certainly seemed to be the case during the flu epidemic of 1918.

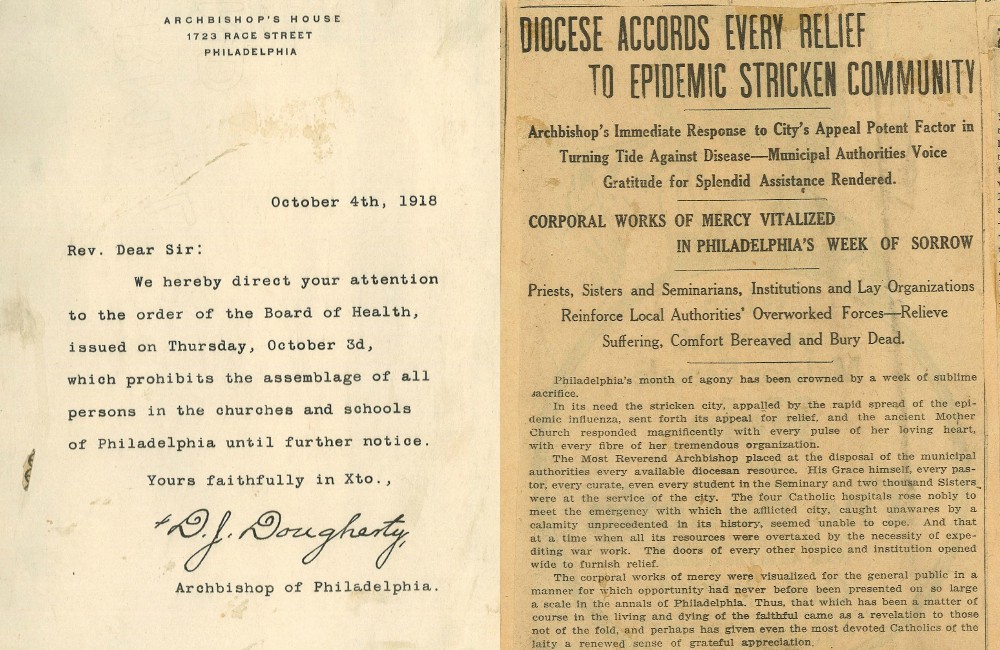

Philadelphia, which had sponsored a parade on Sept. 28, 1918, attracting hundreds of thousands to stir patriotic fervor and encourage the purchase of war bonds, became the American epicenter of the epidemic. It was a time seared on the memories of the older Mercy Sisters, as it was among many local residents.

As thousands became ill, the city began to resemble a scene out of Dante's Inferno. Public gatherings were canceled. Hospitals overflowed, and emergency medical facilities had to be assembled in hotels, garages and schools. Bodies were left in the streets to be taken away by wagons.

Mercy Sr. Patricia Talone (Provided photo)

Talone, the Sister of Mercy, had reasons for asking the older sisters about their pandemic experiences. Her family was deeply affected by the tragedy: Her father, only 5 at the time, lost his mother and older brother. Talone, who worked at the Catholic Health Association as director of ethics and then vice president of mission services from 2003 to 2016, researched the period extensively.

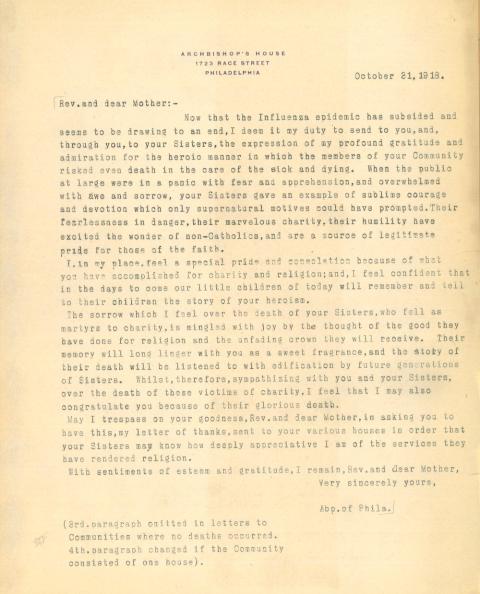

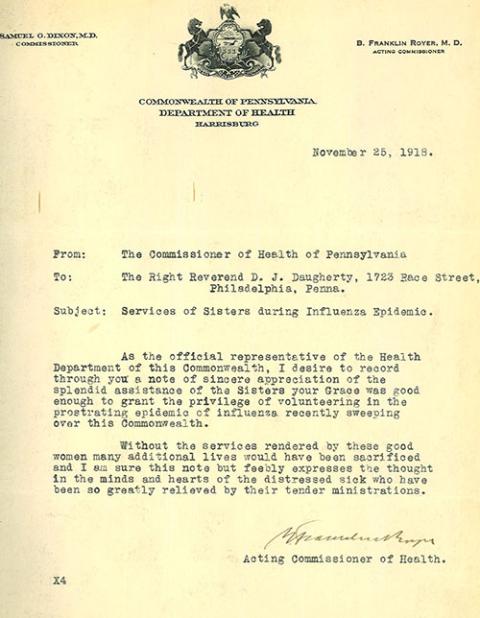

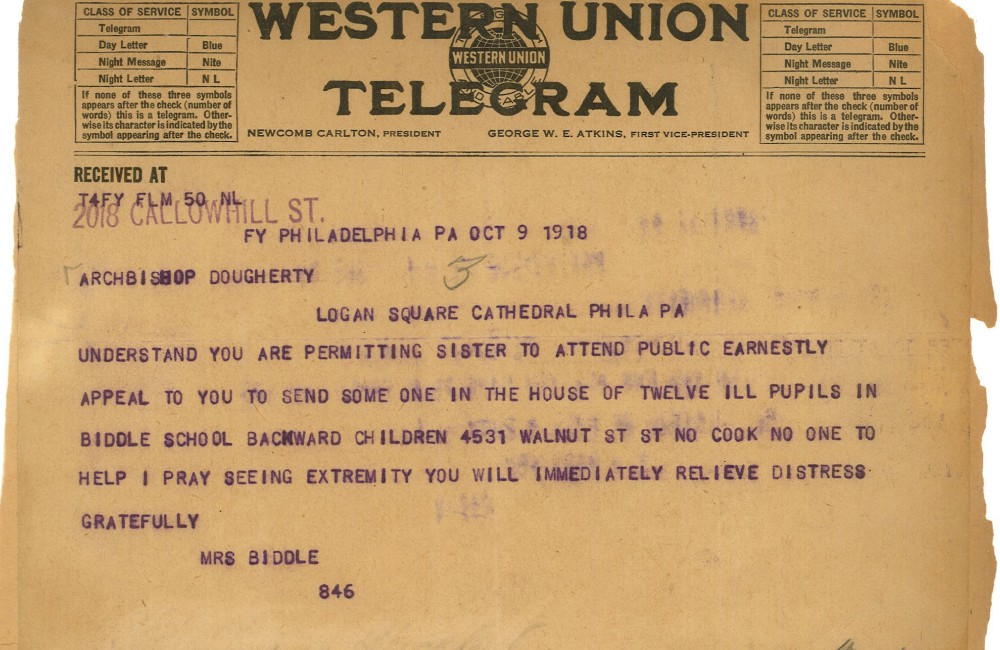

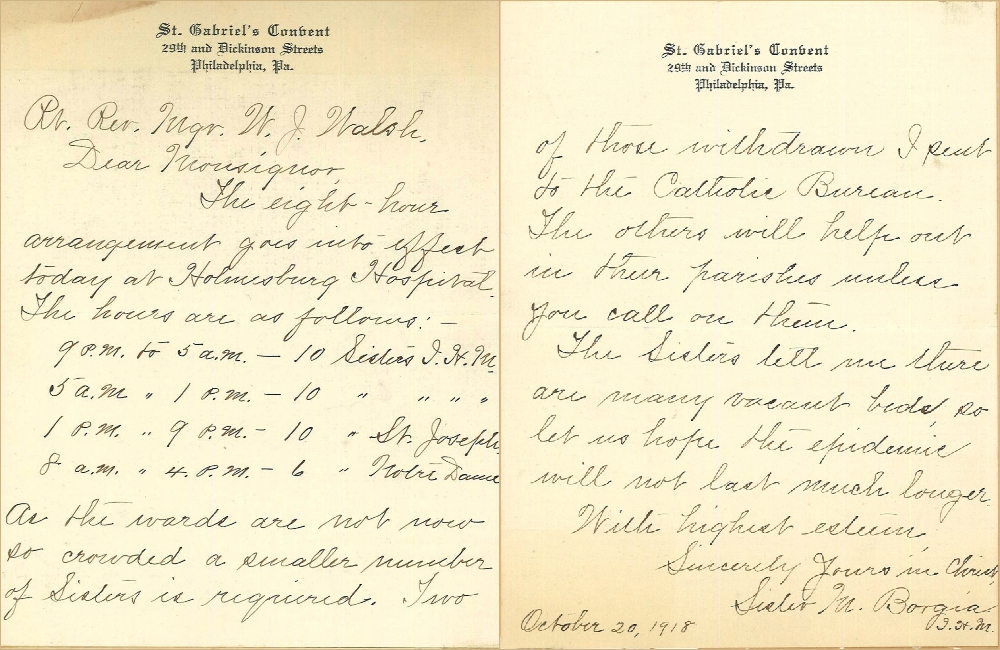

When Philadelphia Archbishop Dennis Joseph Dougherty, like many of his peers in afflicted cities all over America, requested help from religious communities in 1918, he lifted the restrictions that kept women religious within the bounds of schedule and cloistered life.

The nuns, who normally operated under strict social constraints, could now get on public transportation. Some worked the night shift. If they weren't caring for the sick, they were cooking hot meals for the seminarians who were digging graves in local parishes.

The older sisters in Talone's own community reminisced about practices that sound strikingly modern. Arising around 5:30, nuns would attend morning prayers or Mass, if a convent chaplain was available, before going out to their nursing assignments. Arriving home after a long day, "they would be instructed immediately to take off their habits. In the old days, these were commodious outfits. I can't even imagine this."

Only after they had bathed in hot water and put on their clean nightgowns and bathrobes could they receive dinner, she said. After a meal and a blessing, they were each given a glass of whiskey ("This was an Irish order," Talone said) and sent off to bed.

Between 13,000 and 16,000 area residents died (some accounts say 20,000), according to a 2018 exhibit created by the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia that commemorated that tragic year.

In early October, as illness spread through city and suburbs like wildfire, Dougherty, who had been on the job just a few months, banned public Masses and closed parochial schools as well as Charles Borromeo Seminary. Seminarians provided support for staff at local hospitals and were enlisted to dig graves at the overwhelmed Catholic cemeteries.

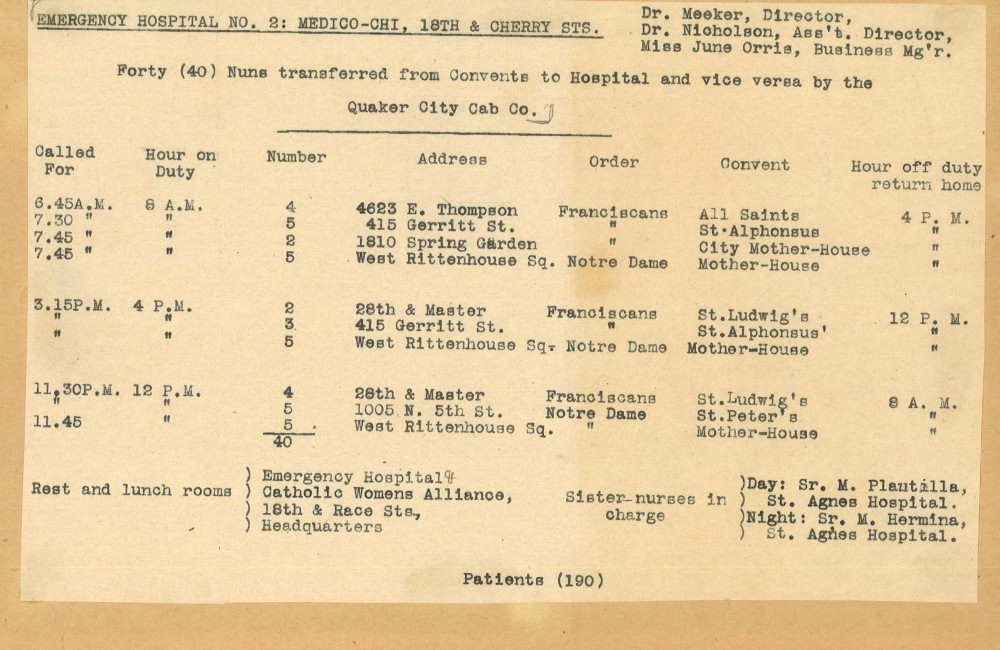

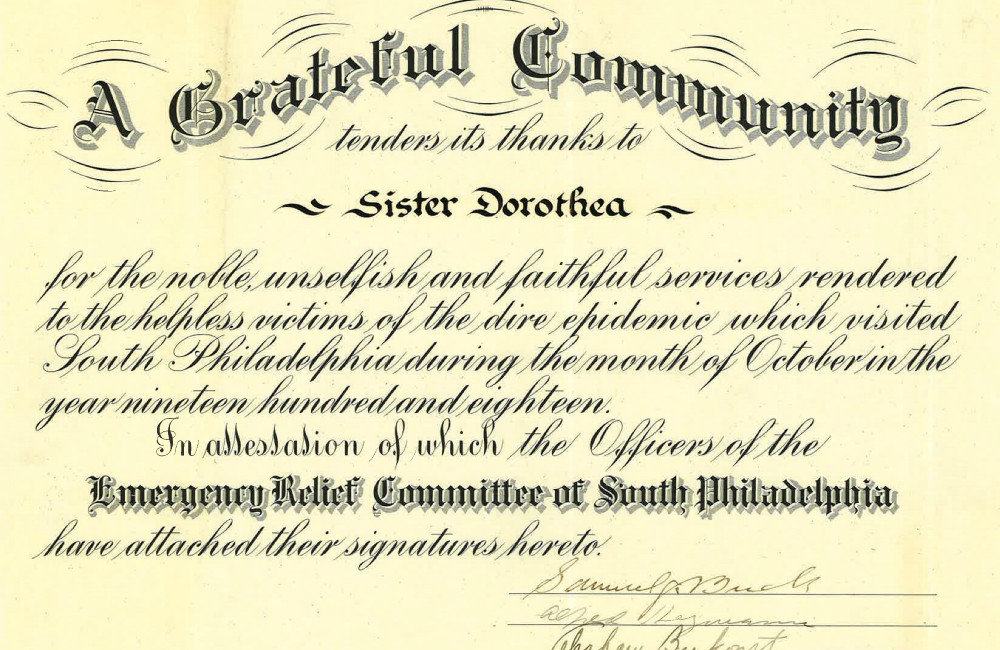

The archbishop called a meeting of major superiors, asking them to encourage sisters to join the swelling ranks of non-Catholic volunteers working in hospitals and homes. More than 2,000 sisters volunteered to help, according to diocesan records. That included many sisters who were not trained nurses, as well as Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis, who at the time ran three city hospitals.

"While we live in a different century, as we engage in pandemic preparation, there is still much for us to learn from those who have so courageously gone before us," wrote Talone in a 2007 article, "All God's Sick Children."

Caring for all

In one instance, according to an October 19, 1918, Catholic Standard and Times account featured in the exhibit, sisters were asked to turn the headquarters of a Catholic club (the Catholic Philopatrian Literary Institute) into an emergency hospital for sick soldiers.

"The sisters promised to have the building ready for patients the following Friday morning, but the physicians were incredulous," reads the clipping. "It could not be done in so short a period, they said. The sisters were equally positive it could be accomplished."

Dr. John M. Fisher, physician at Emergency Hospital No. 3 in Philadelphia, praises sisters in an Oct. 19, 1918, news clipping: "They are incomparable. ... Their only thought and their every care is for the patient. The orders of the physicians could not be carried out more religiously. I am a Methodist, but I must voice my appreciation of their heroism." (Catholic Standard and Times)

In fact, the building was ready for occupants by late afternoon the next day, according to the story.

"It really is a fascinating story," said Patrick Shank, assistant archivist for the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Philadelphia Archdiocese. "They weren't just caring for Catholics. They were caring for everyone."

That work was documented in the Philadelphia region by Francis Tourscher, " Work of the Sisters During the Epidemic of Influenza, October, 1918," which Talone mined for examples to illustrate her article. Because Tourscher was able to interview participants, the book is a rich stew of facts and anecdotes.

At Mount Sinai (a hospital built for Jewish and other immigrants in South Philadelphia now abandoned), Sisters of St. Joseph were called in as nurses, but ended up doing some baptisms as well. "Eight Sisters went to Mount Sinai Hospital," as Tourscher described it. "One detail went early in the morning. When the second detachment arrived, the Superintendent said: 'The Sisters are upstairs and working very hard. It's quite a change from the society ladies who were here last week.' "

Sr. Helene Thomas Connolly (Provided photo)

A Jewish man asked the sisters to pray for him. "I in return will always ask the Great Jehovah to bless you for all you have done for us here," he said.

Approximately 300 Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, one of the larger religious communities in the Philadelphia area, volunteered to serve as nurses or in whatever capacity was needed, said Sr. Helene Thomas Connolly, archivist for the congregation. They traveled from their many mission convents and the motherhouse to beleaguered areas of the city, and out to the boundaries of an expansive diocese.

When the pandemic came to their doorstep, the IHMs set up two emergency hospitals, one on the motherhouse grounds and the other at a school they ran, where they treated members of their own community as well as student boarders.

In several locations, "the sisters worked 12-hour shifts, but often in the evenings, so that the trained nurses could go home and get some rest," she added. They visited the homes of the sick, washed soiled linens, cleaned, cooked and cared for the children, in addition to preparing dinner for seminarians.

Nine sisters, including one novice and one postulant, succumbed to the epidemic, noted Connolly. Remarkably, the toll included just one nurse.

"We had in our wards Greeks, Italians, Jews, Armenians, Negroes, Poles and even East Indians," wrote an anonymous Immaculate Heart sister. "They were all God's sick children and I loved them."

In the Philadelphia area, where tales of the epidemic are still passed down from generation to generation, the memory of these sisters' sacrificial behavior still seems fresh. "We have a great devotion to our deceased sisters, and remember them in our prayers," said Connolly. She credited it to "a great belief that God calls us to the emerging needs of the church and of the world. I don't know how they did it, but it's a source of inspiration to many."

Foreshadowing a pandemic response

Medical professionals have been sounding the alarm about future pandemics for a long time. Talone concluded her article about the 1918 sisters on a note that sounds, in retrospect, eerily prophetic:

Scientific and medical prognosticators warn that we may soon face another such pandemic. Even our modern panoply of pharmaceuticals may not prevent many untimely deaths. In 1918 there was a ready, willing and able cadre of volunteers arising from the many religious orders throughout the country. Today, while the charisms of these orders remain vital, there are not the numbers of religious who will, this time, be able to work directly with the sick and dying.

One of the reasons the sisters had such an impact, says Villanova University professor of historical theology Massimo Faggioli, is that they acted on behalf of the Catholic Church in ways that benefited everyone. "If the church looks only to itself, that's not going to help in the long run. The church needs to act on behalf of the whole society."

During this current pandemic, when physical presence at the Mass isn't possible, but service is, the institutional church has a lot to learn from the leadership of women, he suggested.

But where habited sisters once served on wards and battlefields, visible signs of Catholicism in the public square, Talone now finds reason for hope in the actions of Catholic lay medical professionals on the front lines. Those doctors and nurses, she said, demonstrate a similar kind of altruism, the fruit of Catholic formation programs that train medical staff how to respond. "I feel confident in much of our lay leadership in that regard."

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a freelance writer specializing in religion coverage. She is a frequent contributor to Global Sisters Report.]

Related: During the Last Pandemic, Ursulines Answered the Call