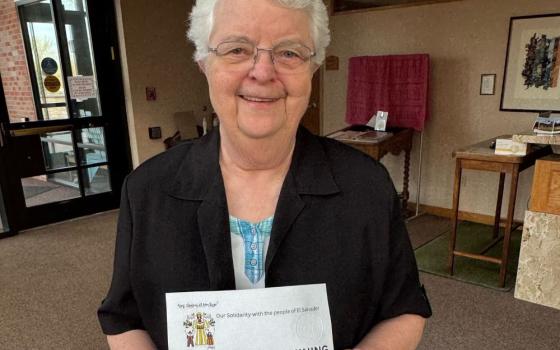

Loretto Sr. Anna Koop in the Denver Catholic Worker House (Georgia Perry)

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Editor's note: More than 1.6 billion people worldwide live in substandard housing. Of those, at least 150 million have no home at all. In this special series, A Place to Call Home, Global Sisters Report is focusing on women religious helping people who are homeless or lack adequate shelter. Over the next few months, we will examine how homelessness and a lack of affordable housing affect teens and young adults, families, migrants, the elderly and those displaced by natural disasters and climate change in stories from Kenya, India, Vietnam, Ireland, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, the United States and elsewhere.

Sr. Anna Koop, a Sister of Loretto, is a Denver-based housing activist who opened the Denver Catholic Worker House in 1978. The original Catholic Worker house had nine bedrooms, but in 2016, it was destroyed in a fire. In 2018, the house reopened in a new form: a four-bedroom home in a block of low-income units purchased and operated by the Catholic Worker over the years.

The city of Denver, which is the 19th-largest metro area in the United States, has experienced nearly 20% population growth since 2010, and the trend is continuing. Along with it, Denver has the most competitive housing market in the United States, according to Forbes, and an increasing homeless population. One effort the city is currently making to address population growth is an update to an ordinance that limits the number of unrelated adults allowed to share a home from two to as many as eight.

Koop has been an outspoken supporter of these changes. She sat down to talk with Global Sisters Report about the Catholic Worker house; growth, gentrification and homelessness in Denver in general; and how the COVID-19 pandemic affects her ministry.

GSR: When did you become interested in housing?

Koop: I have a long history. I've really worked in housing since the '70s. I was working for Denver Catholic Community Services at the time. One of our asks of the city was that they create a mayor's housing task force. In doing that, we were really helping to form housing policy in the city. There were some good tenant-landlord laws that were being proposed. We felt really good about that.

Ultimately, I became pretty disenchanted with the city and the state, the political process that ultimately didn't much care about the people I cared about, people who couldn't house themselves. There was no emergency housing. I mean, the shelters were built after that time. I don't even know if we had "homeless" in our vocabulary at that time. It was more like, "travelers on the road" or something.

I left Catholic Community Services, took a year sabbatical in Santa Fe, and came back with the intention of creating the Denver Catholic Worker House. I concluded that the political process was not getting it done; I should think about providing something myself.

The original Denver Catholic Worker House had nine bedrooms. Having that many unrelated adults living together is against the city's current housing policy, which puts a cap on more than two unrelated adults living together. How did that work?

Thirty-eight years we lived in the house, and we never had a permit. Never. I mean, we always considered it our home, and the people living there were our guests. It's not a nonprofit. It just doesn't function in the way of an agency or a program. It's just offering hospitality in the Catholic Worker tradition, which is to live as equally with the people who are here as possible and function on volunteer help.

The original Catholic Worker house burned down in 2016, and in 2018, it relocated into a four-bedroom house. How has that process gone, in terms of the city's housing policy?

We went to the city to talk about a permit for the house. I can't say the city wasn't kind. They worked with us; they tried to find something. But every time they found something, it didn't fit because the Worker is a very different situation. The current zoning only allows two unrelated adults, but the head of city planning was really on our side, and she managed to bump up the number to four unrelated adults for a permit. So we did get a permit. But we're not up to capacity. We have a room upstairs that's not occupied because of that condition.

That's where the [proposed change to the city's group-living ordinance] comes in. Eight is about what we think the capacity would be here. There's a bedroom downstairs and three upstairs. One of them is really a large family room. That's our hope of what will happen sometime this summer, perhaps.

Advertisement

Can you speak to what it does to a person's psyche, to have a room?

I just think it's a big relief. [Our current guests are] a man and his son from the Republic of Congo. We did a lot of talking on who we would welcome into the house and decided on immigrant people.

Of course, we know that's all around us and such a huge need, with immigration policy changing so horribly and asylum-seekers having to wait long, long periods and by and large coming to this place with no resources. They were totally at survival level for some time. To just be in a place where there's some food and some welcoming people and a sense that it's family-like, people really caring about them, is huge. We have a weekly potluck and prayer.

We always hope for in the process some kind of empowerment. In the old house, the scheduling was you had to be out of the house between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. So people had to be out and about, working on their lives, and if they were able to work, they needed to be seeking employment, and some of those kinds of things.

In the early days of the Worker, people would be able to get their lives together in a couple of months because they could both find a job that gave them a living wage and they could find housing. In the later years, beginning in the 2000s, we had people with us for a year [without finding work or housing]. We absolutely got to the point where we couldn't see ourselves requiring people to be out of the house by a certain time. We would certainly talk with people who didn't seem to be working on things, but we understood that there just wasn't housing available. How could we require that of them when it wasn't attainable?

Could you speak more about that evolution you have witnessed over the years, of the increase in homelessness and decrease in available housing in Denver?

In the last three years, our property taxes on these units have been raised 100%. That's huge. That's just one indication of where housing is going in the city. In the '80s, we were renting an apartment [in this same neighborhood] for $150 [per month]. Between that and now — over $1,000 for a one-bedroom. Huge difference. I mean, it's just outpriced a strata of our population.

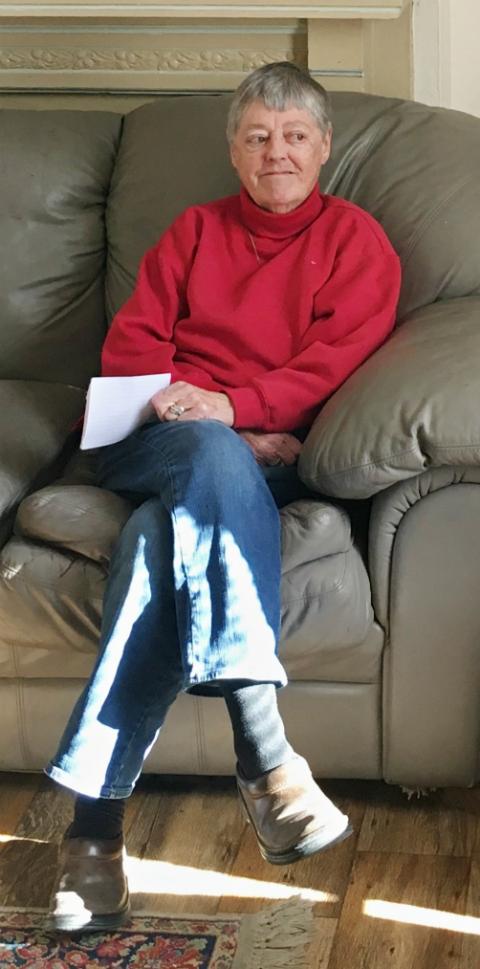

Sr. Anna Koop: "In many ways, Denver is a wonderful place to live, but not for poor people." (Georgia Perry)

Denver's becoming a middle-class city. Poor people live on the streets in tents. I'd say the tents started within the last three years. The mayor passed a camping ban. Through everything, the mayor will not let go of the camping ban. He just will not. [There have been] many attempts to go to him. Which is not to say there aren't some really well-meaning people on the council.

In many ways, Denver is a wonderful place to live, but not for poor people. We kind of bemoan the fact that there's no substandard housing, properties that wouldn't pass inspection. That's what used to be available at $100, $150 a month or whatever. And it just disappeared.

A few years ago, I think the numbers were, "We need 30,000 units for 'affordable housing.' " So you gear up to build affordable housing, and you leverage all this money, etc., and the people at the bottom don't get served at all. The people who need it the most are still not served because they are the no-income, not just low-income.

One thing I would say about the housing policy that is really good is they just don't tear everything down. There has been a consistent effort to preserve the housing that exists. This is turn-of-the-century housing. That's a good thing. The bad thing is that people focus on renovating it, and the neighborhoods gentrify, and the poor people have to move out.

What's your impression of how Denver is addressing gentrification compared to the rest of the United States?

There's a housing crisis in the nation. Denver's especially attractive for people to move here. And the one thing they're doing that I don't particularly care for is production of housing. They're really encouraging growth. And I don't think that's a good idea. But of course, every mayor is going to push that because that's how you be successful at being a mayor. You're expanding. Things are growing. Things are beautiful in Denver.

I wish we would put a cap on growth. Say, "No more growth until our residents are housed." Just no more. No more construction permits until the people here are housed. And you hear, "Well, that can't be. We have to build housing for them." That's not necessarily true. There are places that can be renovated. There are buildings that could be refurbished in a way. We have motels going down all over. Pick those up and make them available at a very reasonable price. There are a lot of alternatives that could happen.

Things can turn around. I don't feel hopeless. But things shouldn't be done in the ever-popular old capitalist ways: If you build housing, you should be able to make a lot of money. You have to get your money back. Not only that, you have to profit.

So thinking of housing as a way to generate profit at all is at odds with your philosophy?

It is. It should be a basic human right. It should be like Medicare. Housing for all.

How has the coronavirus affected your work with the Catholic Worker house?

Probably the most difficult thing for me was the decision to no longer go in and out of the Catholic Worker house. I am one of those vulnerable persons because of my age, and I am a diabetic. We still have contact with folks by phone and occasional conversations outside at social distance.

It is hard to be socially distanced from people you are trying to be supportive of, and they all have their problems. We have definitely experienced kindnesses from our friends who have been bringing food and supplies, and we do have the sense that people in general are doing what they can to help people who are less privileged.

The city of Denver along with a nonprofit organization, Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, recently secured several hundred hotel rooms for people experiencing homelessness to stay in during the coronavirus pandemic. How do you feel about the city's response?

I have a newfound appreciation for the mayor, his housing staff and the city council. Housing, providing health care and food for some 800 men and women is no small task.

Like so many other things during this virus, we are learning that where there is the will, there is a way. The challenge will be when we move away from the needs during the virus time, many of which were there before the virus. Will there be a will politically and economically to really tackle our housing and health care crises, not to mention economic inequities so prevalent in our society? To me, I believe that it is going to require massive systemic change coming from a far more generous place than I have seen operative in our systems for decades.

[Georgia Perry is a journalist based in Denver.]