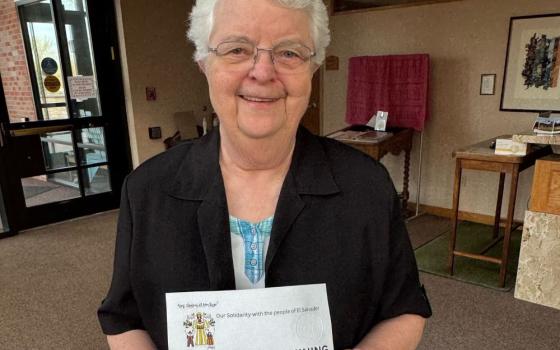

Mercy Sr. Helen Amos at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore. Amos has been the center's executive chair of the board since 1999. (GSR photo / Chris Herlinger)

Editor's note: More than 1.6 billion people worldwide live in substandard housing. Of those, at least 150 million have no home at all. In this special series, A Place to Call Home, Global Sisters Report is focusing on women religious helping people who are homeless or lack adequate shelter. Over the next several months, we will examine how homelessness and a lack of affordable housing affect teens and young adults, families, migrants, the elderly and those displaced by natural disasters and climate change in stories from Kenya, India, Vietnam, Ireland, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, the United States and elsewhere.

In a long and distinguished career, Sr. Helen Amos has put the well-being of the community at the heart of her ministry. A Sister of Mercy for 63 years, she has been a teacher, health care administrator, community leader and advocate for those experiencing homelessness.

Amos, 81, a native of Mobile, Alabama, has spent most of her ministry in Baltimore, Maryland, where she arrived in 1970 to work as a registrar for Mount St. Agnes College (now merged with Loyola University Maryland) following a stint as a mathematics teacher in Georgia. She later became an administrator with the Sisters of Mercy of the Union and the Archdiocese of Baltimore and was president of the Sisters of Mercy of the Union from 1984 to 1991.

Amos has been associated with Baltimore's Mercy Medical Center in different capacities since 1991. She was the center's president and CEO from 1992 to 1999 and has been a member of its board of trustees since 1980. She has been the board's executive chair since 1999.

Under her leadership, Mercy created The Weinberg Center for Women's Health and Medicine, which a biographical profile by the hospital notes initiated "flagship programs in gynecologic oncology and breast cancer diagnosis and treatment."

Amos was recently honored with the Joyful Servant Award from Catholic Charities of Baltimore for her work to make "homelessness in Baltimore rare and brief" through her work for the organization The Journey Home and her leadership in a citywide plan to end homelessness. Previous awards include honors from the Maryland House of Delegates, the Maryland Chamber of Commerce's Business Hall of Fame, the Central Maryland Ecumenical Council, and Loyola University Maryland.

Amos has two degrees in mathematics, including a master's degree from the University of Notre Dame, and she still finds mathematics a useful source of intellectual endeavor and practice in her career.

"It's about logical thinking, about solving problems," she said. At the end of a day of problem-solving, Amos said, "you've accomplished something."

The interview took place Jan. 27 at Amos' office at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore and with subsequent email follow-up. It has been edited and condensed.

Awards are a common sight in Mercy Sr. Helen Amos' office at the Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore. (GSR photo / Chris Herlinger)

GSR: What was the path of becoming a hospital administrator?

Amos: I was trained to teach high school, but I learned early on that being a teacher was not a natural calling for me. To be an educator of high school students, you have to be an extrovert. I'm an introvert. So I became an administrator in different capacities and have now been here for 28 years. As CEO, I always knew my job was to work with people who knew how to run the hospital and let them do their jobs.

As executive board chair, I am able to do things a volunteer chairperson doesn't have time to do, such as cultivate new board members, raise money, make friends for the hospital. Because we are independent and don't belong to a big health system, we really need a very strong community representation — people who are dedicated to Mercy's mission.

Tell us about your activism on homelessness.

Back in the mid-aughts, around 2005, [then-Mayor] Martin O'Malley spoke to me about accepting the role of chairing a group to develop a 10-year plan to end homelessness in Baltimore. That was something a lot of cities were doing at the time. We spent a lot of time getting from the stage of being in a room with a lot of people to translating that into an actual plan. At some point, that began to happen, and I found my role was to speak publicly about the effort, to get people to think differently about who is homeless and why, and to speak about the need for collaboration, what we now call public-private partnership. We didn't have much money to spend on this effort, and the only thing I could contribute was my personal credibility in the community.

People would ask me, "Why do this?" I'd say, "It's the right vision. We should be morally motivated to work on this because it's the right vision." No one should be living in the street, or in a car, or bouncing around from one relative's couch to another.

We ended up doing incremental things. We raised money to fund a children's program coordinator to work in shelters. In the shelters, children had trouble getting to school. Small efforts like that got us started on the 10-year plan. One year, we had a significant fundraiser, a gala, called "The Journey Home," and that name took. We raised a half-million dollars that year, and that helped establish a citywide program to address homelessness in Baltimore. I was involved with that for more than 10 years.

Mercy Sr. Helen Amos at Mercy Medical Center's Chapel of Light, a space used for services, prayer and reflection. (GSR photo / Chris Herlinger)

What were some of the challenges in this work?

The focus then was the idea of housing first, which emphasized getting people off the street while not immediately getting them off of drugs or dealing with other problems. The idea was getting them shelter of some sort. But not every shelter wants it do it that way. There is a need for addressing addiction as well as mental health challenges, the kind of thing social services can provide. So while our plan was built on a housing-first philosophy, it was not easy to get everyone to sign on to our agenda.

What were the visible manifestations of homelessness?

There were a lot of tents in the streets, encampments, not far from the hospital here. We worked on that. We understood that the shelters could be a problem for some people. The shelters wouldn't allow pets, and in tents, people felt some sense of security. "This is where my safety is," they would say. "This is where I can have my pet."

At the same time, we had businesses downtown say, "We can't have people using public space, defecating," that sort of thing. So, we'd offer to move people to shelters where conditions might be better. We worked with the mayor's office to identify people on the street who could be in touch with the city about where to go.

Do you feel you ended homelessness in those 10 years?

No. We tried to prioritize what we could realistically work on. We encouraged the development of more affordable housing. We focused on advocacy and helped expand medical services for the homeless. We worked on expanding and improving the shelter system. We kept chipping away at the problem, and the city is still doing that.

Mercy Medical Center's Chapel of Light, a space used for services, prayer and reflection (GSR photo / Chris Herlinger)

What do you think is the cause of homelessness?

The lack of affordable housing is the first thing. In the 1970s and then in the 1980s, there was a lot less funding to make it possible to build affordable housing. If the federal government is pulling away from that, as it did, it is less and less possible to build affordable housing.

We have probably 3,000 people at night on the street in Baltimore, and perhaps 10 times that amount in substandard housing. Why is that? There's structural racism — Baltimore has had a very troubled history of redlining. There is a lack of jobs and lack of a living wage for the poorly educated. We see the stark contrast here in Baltimore: There is a lot of attention to the Inner Harbor area, a highly developed area where there is new housing, but only for those who can afford it.

Has society done enough to focus on homelessness?

Overall, no. But when there are concerted efforts, things can happen. During the Obama administration, there was a policy to reduce to "functional zero" the population of homeless veterans. It worked. The initiatives, such as creating and tracking an actual roster of homeless veterans and focusing on their individual cases, worked well enough so that some cities actually achieved "functional zero" homelessness among veterans. When there is a focus on a problem, things can happen.

Is there something about the charism of the Sisters of Mercy that has made your congregation particularly sensitive to the needs of those experiencing homelessness?

In the 1980s, we sold our motherhouse in Bethesda, Maryland, and created a fund to address ministries focused on homeless children and mothers. I wasn't the president of the congregation at the time, but I was the successor to that person, and I know that what happened followed the example of our foundress, Catherine McAuley, whose ministry was focused on the needs of the economically poor.

Our medical center has provided health care for those experiencing homelessness; I've raised money for that initiative. We've adopted the saying, "Housing is health care," and we've advocated for that. If you are diabetic and homeless, how are you going to take care of your medicines, your supplies? To be homeless is a health issue, and providing housing is one way to address this issue.

Where do you find spiritual grounding and sustenance?

Prayer. I depend on daily Scripture readings. I say the rosary daily. I find that going through these mysteries keeps me grounded. When I'm looking at societal problems, I find the most important thing to do is to maintain hope. It's only if you have hope that you can face these issues and judge them with the idea that things can be made better.

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]

Advertisement