Sr. Caroline Ngatia shares breakfast with the street families in Nairobi, Kenya. The nun has been feeding the underprivileged children for years and, as a result, the kids simply call her "mum." (Doreen Ajiambo)

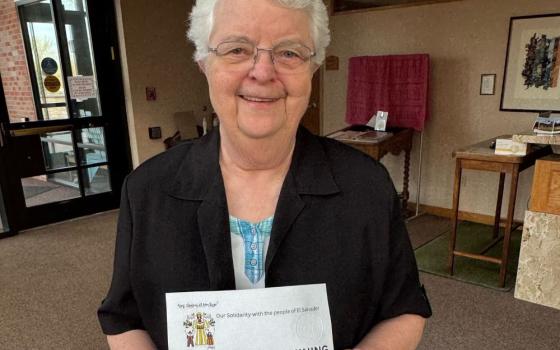

(GSR/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Editor's note: More than 1.6 billion people worldwide live in substandard housing. Of those, at least 150 million have no home at all. In this special series, A Place to Call Home, Global Sisters Report is focusing on women religious helping people who are homeless or lack adequate shelter. Over the next several months, we will examine how homelessness and a lack of affordable housing affect teens and young adults, families, migrants, the elderly and those displaced by natural disasters and climate change in stories from Kenya, India, Vietnam, Ireland, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, the United States and elsewhere.

It's early in the morning and Sr. Caroline Ngatia walks the freezing streets of the capital here, looking for homeless children. As she makes her way through the busy crowds of the downtown business district, young street children emerge from cardboard boxes, doorways and cellars of the dilapidated buildings. The children fling themselves at her, seeking the companionship and love they otherwise lack.

Tens of thousands of children are living on the streets of Nairobi — some forced out by poverty, violent home lives and family breakups. Children have lost their parents. And many families have been displaced by demolition of their homes and apartments to make way for a multimillion-dollar highway link to the Trans-African Highway. The government says the homes were built unsafely on public land, right-of-ways, wetlands and waterways without official approval.

Ngatia is confronting the problem of street children head on by providing meals, shelter and education for some of them.

"I always feel like crying whenever I see a child sleeping in the cold and without a meal," said Ngatia, breaking down in tears and having to be comforted by some of the street children. "It is disheartening to see these children suffering."

Srs. Caroline Ngatia (at left, in white veil) and Caroline Cheruiyot (far right) and members of the staff work together on behalf of the street children, some of whom are pictured here, at Kwetu Home of Peace in Nairobi, Kenya. (Doreen Ajiambo)

Ngatia runs Kwetu Home of Peace, where homeless boys ages 8-14 are plucked three times a year from the streets and slums in Nairobi and elsewhere and inducted into a process of reintegration. The goal is to reform and rehabilitate the boys through counseling, games, drama and useful life skills, such as house cleaning, agriculture and carpentry, she said.

In Kenya, girls are less likely to end up on the streets, due to legal protections and help from volunteer organizations working on their behalf. Conversely, boys are more often left to take care of themselves.

The sister says the displacement has complicated the rescue mission and spurred an increase in the number of street children.

"We have assisted families and rescued some of the children as a result of house demolition because they had nowhere to go," said Ngatia of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Sisters of Eldoret in Western Kenya. "I want to see these boys one day becoming productive members of society so that they can come back and assist more street children and end the street families menace within the country."

There are no official government figures on the number of homeless children in the East African country, despite the rising numbers of them in Kenya's major cities and towns. However, an estimate by the London-based Consortium of Street Children puts the number at 250,000-300,000, with 60,000 in Nairobi alone.

Ngatia believes the number is much higher.

The road to ending up on the streets

Wearing gray, faded trousers with a black shirt, a boy named Evans sits quietly on garbage heaps at the infamous Dandora dumpsite on the outskirts of Nairobi. Amid swarms of flies, stench from rotting garbage and human waste, he narrates how he found himself in the streets after his family's house was demolished in Kibera on June 21, 2018.

"We used to live in a shanty house where we could not pay rent," said the 15-year-old boy, who joined the street early last year. "When bulldozers kicked us out of the house, we were forced to spend five nights in the cold because my parents are poor and they couldn't afford to rent another house."

Thousands of families have been left homeless in Kayole slum in Nairobi, Kenya, as a result of demolition by the government to make way for a new highway link and housing developments. (Doreen Ajiambo)

Evans was taken to a neighbor to allow him to prepare for his national exams as his parents decided to go back to the village after being offered a lift by a good Samaritan, he said.

"The neighbor used to deny me food and beat me every day," said Evans, who sat for his Grade 8 exams in November 2018. "When I finally finished my exams, she chased me away and I ended up on the street. I later heard that my mother and father had divorced and neither of them wanted to see me. I had no option but to stay on the streets and beg. I do all sorts of work to ensure I get something to eat."

Activists and other leaders have condemned the evictions, but Kenyan officials said the people living in the areas earmarked for demolition were there illegally.

"They deserve to be treated in a humane manner because these are old women with their children," said Esther Passaris, an opposition Member of Parliament representing Nairobi County. "Their houses were demolished in the dead of the night and families had to spend the night in the cold. We have to assist such families with food and try to help them resettle, otherwise they will end up on the streets."

Some families have not been resettled, forcing thousands of children onto the streets to fend for themselves and making it difficult for nongovernmental organizations to end the dangerous situation.

The boys on the street say they are exposed to starvation, violence, sexual exploitation, poor sanitation, substance abuse and emotional torture. Motorists often beat them up, Evans said, presuming they are looking to steal car parts, while others hurl insults at them whenever they ask for food or money.

Some of the boys fall prey to whatever diversions they can find.

A new habit forms

Mlango Kubwa, one of the fast-growing Nairobi suburbs, is home to thousands of street kids. Here, many of them sniff contentedly on their bottles of toxic glue, constantly walking the streets and alleys, scavenging for anything they can turn into cash and begging for a meal.

The teenagers hanging out together in Mlango Kubwa, however, are a different lot. Looking dazed, they rummage for food and discarded items to resell. Weary younger children sleep on the piles during the day.

These kids are sniffing jet fuel, which they call mssi in their hybrid slang. "We get it from town, we really do not know where it comes from and we do not ask. We just take it like people drink pombe [beer]," says one of the boys. "It gives me a high and helps me deal with stress in these bad streets."

Jet fuel is now the intoxicant of choice among many street children. It looks like water and they carry it in small plastic bottles. Anyone who has some is revered here.

A homeless boy sniffs toxic glue on the streets of Nairobi, Kenya. Street children do this to beat hunger pangs, stay warm and feel good from the high, but health officials warn that glue sniffing presents a serious danger to them. (Doreen Ajiambo)

Most of the boys who use it have scars on their faces from falling flat after the dizzying effects of the first sniff, says Ngatia.

Thomas Ngumu, a psychologist at Kwetu Home, has tried to help them kick the habit.

"It's not an easy thing to do," he said, shaking his head. "They are sniffing a new substance that turns them into near zombies."

Jet fuel can render a user confused and hostile from hallucinations or can cause unconsciousness and rashes around the nose and mouth, Ngumu said, adding that it can result in death from suffocation caused by the chemical entering the lungs and central nervous system.

A government struggle

Kenyan authorities have tried to rehabilitate street children from the major towns of Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu and Eldoret, but their efforts have failed because of ineffective approaches, those working on the problem say. Street families normally would be detained and locked up. Soon after release, they would return to the streets and start over again.

For the last two years, officials in Nairobi have rescued more than 1,000 street children, with most of them taken to four government rehabilitation centers — in Shauri Moyo, Joseph Kang'ethe, Kayole and Bahati.

"We care for street children and my administration will continue to rehabilitate them," said Mike Sonko, governor of Nairobi County. "When I was elected, I promised to ensure all street children are taken to orphanages and rehabilitation centers. I'm going to fulfill my pledge."

A street child sleeps on a sidewalk in Nairobi, Kenya. There are many socioeconomic factors in families that contribute to the increase of street children in Kenya. These include poverty, lawlessness, alcohol and drug abuse, social permissiveness, family breakup and child abuse. (Doreen Ajiambo)

Sonko, a colorful national figure who is facing corruption charges, won a 2019 award sponsored by the Kenya Red Cross and United Nations Volunteers for promoting volunteering.

Ngatia reported that last year the government disbursed more than $30,000 to assist some of the street children at her center.

However, she said, for the government to address the current crisis, it must first tackle the factors that push children to the streets.

"There are reasons why street children have no home and sleep on pavements," said Ngatia, who is also a trained teacher. "Let's deal with the root causes and stop associating street families with drug abuse," she said, conceding that the homeless sometimes turn to drugs to ease their lot.

She urged the government to invest in social protection and create employment for young people to avoid a situation where children move from rural areas to towns to look for jobs but end up on the streets.

Sr. Caroline Cheruiyot, who works at Kwetu Home of Peace as a counselor, said their intention is to mentor the boys to achieve their dreams by offering them education and identifying and developing their talents. Street children need total rehabilitation, which involves a range of activities, such as providing them with life skills, counseling, and recreational activities to enable them to shed drugs and street habits, she said.

Advertisement

A sign overlooking the common area at Kwetu advises, "Jump, Shout, But Do Not Sin."

"When these children come here, they are taught the way to live life like normal people," said Cheruiyot, who is also a communications lecturer at Strathmore University in Nairobi. "We rescue, rehabilitate and reintegrate them. We specifically deal with the boys because they are not well taken care of like the girls."

The sisters have some success stories about former street children who are pursuing their university education, and others own and manage businesses.

Paul Thuo, a former street boy, is now pursuing his university education after he was rescued by the sisters from the streets and taken to Kwetu when he was young. His parents died and he was forced to live with his aunt who he says used to beat him and hurl abuses at him.

"Life was unbearable and I had to run from home and start providing for myself," the 20-year-old said, adding that his aunt used to leave him in the house without food. "I thank the sisters for changing my life. I will commit to assisting street children after I complete my education."

Ngatia says her center is able to take in only 60 boys every four months. But it's a drop in the ocean, and most of these children have no help at all, she adds.

"It's our desire to take everyone from the street, but our biggest problem is funding," she said, noting that many donors prefer supporting girls rather than boys. "I have a dream that one day when we come together as a country, we will end the street families menace."

Editor's note: This story has been updated on July 27, 2020, to remove two photos.

[Doreen Ajiambo is the Africa/Middle East correspondent for Global Sisters Report.]