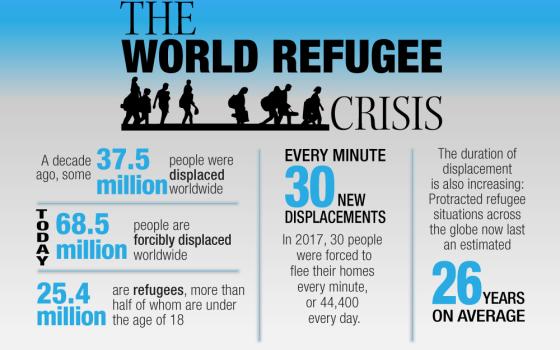

Editor's note: More than 68 million people had been displaced from their homes because of factors such as war, threats from gangs, natural disasters, and lack of economic opportunities at the end of 2017, the highest number of displaced since the aftermath of World War II. Of those, the United Nations considered 25.4 million to be refugees: people forced to leave their countries because of persecution, war, or violence.

Over the next several weeks, Global Sisters Report will bring a sharper focus to the plight of refugees through a special series, Seeking Refuge, which will follow the journeys refugees make: living in camps, seeking asylum, experiencing resettlement and integration, and, for some, being deported to a country they may only vaguely remember or that may still be dangerous.

Though not every refugee follows this exact pattern, these stages in the journey are emblematic for many — and at every stage, Catholic women religious are doing what they can to help.*

______

An anguished world is on the move.

Syrian refugees fleeing a brutal war reinvent their lives in Jordan, most in cities and towns, while thousands of others dwell in camps that are quickly becoming permanent communities.

The same is true in the crowded settlements in Uganda, where refugees escaping the agonies of war-torn South Sudan continue to seek refuge.

Thousands of Venezuelans cross the border daily into Colombia, fleeing economic and political upheaval; some 200,000 registered as undocumented migrants, though the Colombian government estimates there may be more than a half-million.

In Europe — the destination for many fleeing the Middle East and Africa — the continent is divided by internal debates about how to respond to the flow of people. After an uprising in refugee detention center last month, the German government vowed to get tough on deporting unsuccessful asylum seekers.

By contrast, Catholic sisters in France advocate for the most vulnerable refugees, including single women facing persecution and other dangers in their home countries. Sisters aid refugees in "port of entry" countries like Italy and Greece.

Along the U.S.-Mexico border, sisters assist asylum-seekers and those deported from the United States. And amid rising anti-immigrant sentiment in the U.S., Catholic women religious across the nation help refugees, join other faith leaders to speak out against family separation and take public positions to counter fear and anger.

It is an unprecedented moment — a global issue confronting national governments, the United Nations and the Vatican. As Catholic organizations and congregations join other religious and humanitarian groups to assist those directly affected, they also work to overcome perhaps an even larger challenge: Opening hearts and minds to the plight of refugees.

This week, they will do so by marking United Nations' World Refugee Day on June 20, and with grassroots initiatives and awareness campaigns such as Share the Journey, an on-going effort launched last fall by the Vatican to highlight Pope Francis' call to "welcome the stranger."

Among those joining in this effort are Catholic Relief Services, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Catholic Charities, and Caritas Internationalis. Jesuit Refugee Service is also endorsing the campaign.

The efforts of the church represent a needed antidote to the hostile reaction to refugees in many countries.

"The people who are arriving are not terrorists," said Sacred Heart Sr. Florence de la Villeon who heads the refugee ministry of the International Union of Superiors General (UISG), a membership group of leaders of 2,000 women religious congregations. "They left their homes because they wanted a better life. To me, it's not the numbers, it's the suffering of the people."

Causes for the current movement of people globally are multi-layered and often overlap: wars, political unrest, economic dislocation and the effects of climate change all contribute to more than 68.5 million people around the world being forced from home in what UNHCR, the United Nations' refugee agency, calls "the highest levels of displacement on record." Among them are nearly 25.4 million refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18.

Western countries must recognize both the gifts refugees bring and that orderly integration and resettlement is a needed moral and pragmatic response to the problem, de la Villeon told GSR during an interview in Rome. "We have no other choice. We have to do it. They [refugees] are here."

From her vantage point as one of the top Vatican officials involved in the refugee crisis, Flaminia Vola sees evidence of rising anti-immigrant sentiment in the region — but also the efforts to counteract that response.

"There are many, many good examples of good experiences [of welcome and hospitality], and we have to share those good experiences with the world," said Vola, Western Europe regional coordinator for the Migrants and Refugees Section of the Vatican's office for Integral Human Development. She is surrounded by reminders of what is at stake: In a conference room stands a sculpture of a group of migrants with an accompanying inscription from Hebrews 13:2: "Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it." And down the hall in a glass case is a lifejacket given to Pope Francis by a group of rescuers who assisted migrants on the Mediterranean Sea.

"Our consciousness is only waking to this," said Loreto Sr. Patricia Murray, executive secretary of UISG. Murray takes the long view, saying that the current trends are likely to continue. "It's a new moment for the world," she said in a recent interview in Rome. "We're on the threshold of something massive."

While some nations and communities welcome newcomers, anti-immigrant sentiment is resetting the political landscape in many European countries and the United States. Newly re-elected Prime Minister Viktor Orban of Hungary and U.S. President Donald Trump say nations need to protect themselves and argue that newcomers pose a danger and portend unwanted changes.

Nationalist movements in Italy and Spain are gaining strength, and earlier this month a right-wing party in Slovenia advocating an anti-immigrant platform won parliamentary elections.

The "ultra-right" in Europe and elsewhere is driving an agenda that "works on the fears of people," said Sr. Elisabetta Flick, an Italian sister who heads a UISG ministry to assist arrivals on the Italian island of Sicily. By contrast, countries with some of the fewest resources, such as Uganda and Kenya, have welcomed refugees in large numbers and host some of the world's largest settlements.

Still, in Italy and elsewhere a core of people committed to welcoming migrants and refugees exists, Flick noted. "You can find people [everywhere] with a big heart," she said. Indeed, a recent report on social innovation among Catholic parishes, dioceses and organizations to respond to the refugee crisis outlined 64 projects, more than half affiliated with Catholic women religious congregations.

Flick credits many diocesan leaders in Italy for declaring the need for people "to live together," and she and others praise Pope Francis for his outspoken stance for welcome and compassion toward refugees and migrants.

Francis, whose father was an Italian immigrant in Argentina, has warned about the "the globalization of indifference" toward the plight of refugees and migrants and made migration the centerpiece of this year's annual World Peace Day message — a theme he repeatedly makes in public appearances and statements.

"In a spirit of compassion, let us embrace all those fleeing from war and hunger, or forced by discrimination, persecution, poverty and environmental degradation to leave their homelands," he said.

The pope reiterated that theme last month during an audience with new ambassadors presenting their credentials to the Holy See. "Among the most pressing of the humanitarian issues facing the international community at present is the need to welcome, protect, promote and integrate all those fleeing from war and hunger, or forced by discrimination, persecution, poverty and environmental degradation to leave their homelands," Francis said May 17, quoted by the ANSA news agency.

Francis acknowledged the challenges in the church's position, saying that the idea of "welcome" is not merely rooted in good intentions.

"Welcoming others requires concrete commitment, a network of assistance and goodwill, vigilant and sympathetic attention, the responsible management of new and complex situations that at times compound numerous existing problems, to say nothing of resources, which are always limited," he said in his World Day of Peace message.

In that message, Francis also addressed national leaders who, he said, "are sowing violence, racial discrimination and xenophobia, which are matters of great concern for all those concerned for the safety of every human being."

All indications, he said, are that "global migration will continue for the future. Some consider this a threat. For my part, I ask you to view it with confidence as an opportunity to build peace."

It is also an opportunity to build global agreements and frameworks. The Holy See's Migrants and Refugees Section has a robust advocacy campaign and is taking an active role in the United Nations' current debate of two global compacts, one on refugees and one for "safe, orderly, regular and responsible migration."

Sr. Gabriella Bottani, an Italian Comboni Missionary Sister who is the coordinator of UISG's anti-human trafficking network called Talitha Kum, credits the pope with taking what may be an unpopular position, even among many church members.

In her ministry, she continually points out that "trafficking and migration go hand-in-hand," Bottani said, noting that more than half of those who cross borders are trafficked, usually by smugglers. "Migrants are one of the most vulnerable groups today," she said.

Pope Francis reiterates this sense of vulnerability in his appeals, and is trying to "awake a [sense of] humanity we're losing." This contrasts to politically heated rhetoric that often believes "if we are able to 'stop the migrants,' that will solve the problem [of people migrating]," she said. Those in migration ministries, Bottani said, "know that that's not a real solution."

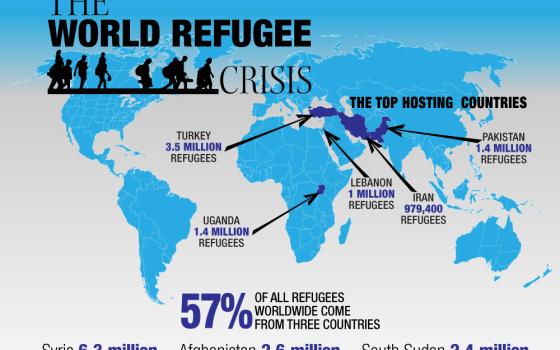

Fifty-seven percent of refugees globally come from three countries, UNHCR notes: Syria (6.3 million), Afghanistan (2.6 million) and South Sudan (2.4 million). In all three countries, fear, violence and repression are prompting huge flights of migrants.

In the case of South Sudan, "people are afraid of night attacks," said Sr. Yudith Pereira Rico, the associate executive director of Solidarity with South Sudan, one of UISG's ministries and a regular visitor to the war-torn country. "It's real, this fear," said Pereira, a member of the congregation The Religious of Jesus and Mary.

One Catholic priest whose family fled to neighboring Uganda told Pereira that despite living in a refugee camp now, " 'At least my family can sleep.' "

When there is protracted conflict, impunity and lawlessness — as there is in South Sudan as well as Syria and Afghanistan — people feel trapped, she said.

"If you don't have justice, what do you build on?" Pereira told GSR. "People want peace, school, health care, an ordinary life. They are hungry for that."

Long-term conflicts prevent development, Pereira said, and when that happens, "a country gets stuck. If people remain, they have nothing. Their future stops. People need a future."

The challenge in a time of enormous change globally, Murray said, is to understand that "when you have great shifts, the first reaction is often fear."

In addition to dislocations caused by war, the shifts underway are part of the ever-evolving human story, Murray said. "It's the phenomena of people seeing opportunities and seizing them. It's the same pattern, with the Irish in the U.K., Australia and the United Nations," said Murray, who is Irish. "It's a worldwide pattern: people wanting to work, having a decent life."

To combat that fear means figuring out how those who live in countries and communities and those arriving can find ways "to create a culture of encounter, community, welcome and hospitality," Murray said, while also recognizing it won't be easy, as Pope Francis says.

"We have to see it in terms of the community and how we live together with our diversity," she said. "We welcome the stranger because we're strangers ourselves. We're strangers to one another."

*This story was updated June 20 with new statistics on refugees and people on the move from UNHCR.

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]

Next in this series: After years of their own displacement, Ugandans offer sanctuary to South Sudanese, becoming a top host country for refugees