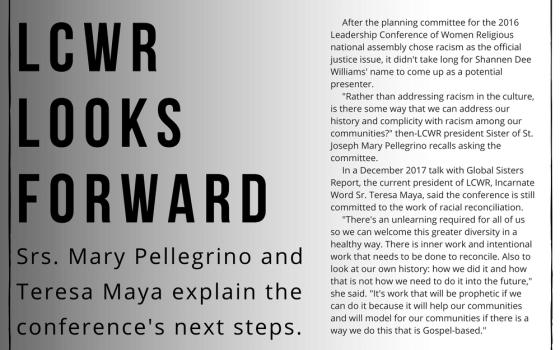

When historian Shannen Dee Williams took the stage at the 2016 Leadership Conference of Women Religious national assembly in Atlanta, she had already been working on her book about anti-black racism among Catholic sisters in the United States — Subversive Habits: Black Nuns and the Long Struggle to Desegregate Catholic America — for nine years.

Yet it wasn't until this particular presentation on the ways black women have been excluded from and mistreated by predominantly white religious congregations that white sisters really became familiar with her work. Once she left the stage, Williams said, the invitations to cull previously inaccessible archival material started rolling in.

As of fall 2017, five congregations have opened up their archives to Williams: the Sisters of Mercy, the Dominican Sisters of Peace, the Sisters of Charity of New York, the Loretto Community and the Sisters of St. Joseph of Baden, Pennsylvania. In fact, so much new information became available that Williams had to postpone the deadline for her book.

Immediately following her presentation, Williams also started receiving invitations to speak at various motherhouses; women who heard her presentation at the LCWR assembly were eager to share this history with their wider sisterhood.

For Williams, this wave of interest in her work epitomizes the complex relationship white women religious have with anti-black racism. White sisters seem to be the members of the Catholic Church most open to a process of self-reflection when it comes to racism, and yet anti-blackness has been a defining feature of religious life in the United States. Williams says it's no accident that some of the formal policies that kept black women from entering certain religious communities were upheld through the 1980s.

Some congregations, she told Global Sisters Report, regularly took votes on whether they would admit "colored" or "negro" women and, for generations, decided against it. In one post-World War II story Williams has unearthed, when a candidate with a French-Creole surname failed to disclose her race in a letter of inquiry to a white congregation, the major superior wrote to the woman's school, asking, "Is she a Negro?"

"The Catholic Church's record on racial justice is not good," Williams said. "And if we want to give credit to sisters for building the church, they are also deeply implicated, then, in the church's failure to be a living witness for racial justice — for its failure and, arguably, ongoing failure to say that black lives matter."

'We bought into the culture'

Sr. Anne Lythgoe, a Dominican Sister of Peace, can't pinpoint exactly why it's taken white sisters this long to address their own racism and implicit bias, though she offers up the Buddhist concept that when the student is ready, the teacher comes.

"I think that's what has happened for religious women and for Catholicism in the United States — we're kind of ready to hear this hard truth, and Shannen was given the gift of being the person to explore this and really help us understand it."

Lythgoe heard Williams' LCWR presentation and was captivated; but she was frustrated that Williams wasn't given more time to speak. So she, along with other members of her congregation's leadership team, invited Williams to travel to Columbus, Ohio, in the summer of 2017 and give a presentation that was webcast to nine satellite locations. Williams' presentation also kicked off the Dominican Sisters of Peace's yearlong study of racism and "encountering the other."

Sr. Michele Dvorak, first councilor of the Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ, also heard Williams speak in Atlanta and could not wait to share what she had learned with her congregation.

"Her presentation was riveting and showed so clearly the sin of racism that is in our religions communities. You couldn't walk away from that and be untouched," she said.

Before long, Dvorak had arranged for Williams to speak at the Poor Handmaids' 150th anniversary celebration taking place in June 2018. She said she's planning to couple Williams' presentation with a panel featuring young women religious of color that she hopes will help teach her sisters how to move past the "sin history" of racism both corporately and individually.

"The shocking reality is that we bought into the culture of racism that was existent in our culture. We're just what the society and culture of the time places in us," Dvorak said.

The idea that anti-black acts are the purview of a past "sin history" that was fed not by the sisters' own racism but the culture in which they lived is popular among today's well-meaning white sisters. Sr. Miriam Najimy, U.S. provincial of the Daughters of the Heart of Mary, for example, gives a similar explanation for her congregation's exclusionary practices.

"A lot of the decisions that were made in the past, as far as inclusion was concerned — we didn't have the awareness then," she said. "We're products of our time, we're products of our cultures. The culture, fortunately, has changed and has grown."

Like the Poor Handmaids and the Dominican Sisters of Peace, the Daughters of the Heart of Mary also reached out to Williams following her appearance at the 2016 LCWR assembly.

The Massachusetts-based congregation coordinated with the Sisters of Providence of Holyoke, Massachusetts, and the Sisters of St. Joseph of Springfield, Massachusetts, to bring Williams to Holyoke in February 2017 for a presentation. They invited every sister in New England to attend. The most severe snowstorm of the year kept attendance to about 80 sisters (more than 200 had registered), but Najimy said it was a "wonderful" event nonetheless.

"Those who were able to attend, in spite of the stormy weather, were very impressed with her — with her whole demeanor, her whole attitude, her whole openness and the respect that she shows for women religious," she said.

Najimy was also pleased that Williams did not make allegations about white sisters or accuse them of anything.

"It was just telling history the way it was. Very objective," she said.

But as Williams continues to inspire predominantly white congregations to come to terms with their complicity, past and present, in anti-black racism, it seems almost certain that they will have to grapple with allegations and accusations of some kind. The question, then, is what do the sisters do about them?

The way forward

Racial reconciliation is intersectional and nuanced — think Georgetown University's attempt at facilitating justice by bestowing legacy status on the descendants of the enslaved blacks the university sold in 1838 only to be critiqued by public thinkers in both black niche and more mainstream media outlets.

For Najimy, the way forward for women religious is behavioral. Enlightened white sisters are now tasked with moving toward "a more open, receptive and respectful attitude toward people of all backgrounds." Women religious in general and LCWR in particular are rapidly heading toward this place of conscious evolution, she said.

Williams, however, suggests a more concrete approach: If white sisters want to reconcile with the black women who suffered at their hands, they should consider following the examples of the Sisters of Mercy and the Sisters of St. Joseph of Baden, Pennsylvania, both of which have extended formal apologies to black women who were rejected by their congregations (the former beginning in the 1990s, before Williams started her work).

"We have to understand what that [rejection] means, because vocations come from God," Williams said, "When you have someone saying that your God-given vocation is not welcome, is not real? Quite frankly, it's an evil practice."

Based on what she has observed, Williams says the formal apologies have been meaningful to the women who have received them, but she cautions that they are only a first step. The process of excavating centuries of conditioned white supremacy is not easy — even for Catholic sisters.

Yet her book is not meant to be a primer in reconciliation for white sisters. She has deliberately centered the experiences of black women, not so they can serve as "intellectual Mammies" — a phrase coined by journalist Stacey Patton — but so their voices can be given their proper place in the history of a church that has tried to suppress them.

Williams is not ambivalent: Both white women religious and the Catholic Church at large have a long way to go in terms of racial justice. It is not lost on her that some predominantly white congregations still refuse to take her calls.

However, Williams says she's heartened by the white sisters who are trying to do the right thing; her book hasn't even been published yet, and the response to it has already exceeded her wildest dreams.

"It's deeply encouraging," she said. "Justice comes after acknowledging and then remembering — from institutionalizing the memory of injustice so that it cannot happen again."

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is a Global Sisters Report staff writer. Her email address is daraujo@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @dawn_cherie.]

Related - A sisters' community apologizes to one woman whose vocation was denied,

NCR in conversation: Listen to a podcast with the author

Recognizing racism: my own journey

and Letter to the editor: Franciscan Sisters of Mary provided opportunities for all women