Kochurani Abraham, a feminist theologian, left a congregation of women religious to lead an independent religious life in her home state of Kerala, southern India.

Her name, "Kochurani," means "little princess." Although born in a traditional Catholic family, she said religion did not attract her when she studied in Catholic schools in Kerala. However, a Catholic youth program she organized made her rethink her values. She said it awakened a dormant spirituality in her life that made her sensitive to the marginalized.

The 57-year-old scholar has a doctorate in feminist theology from the University of Madras in southern India. She completed her bachelor's degree in theology from St. Pius College in Mumbai, western India, and licentiate in systematic theology from Comillas University in Madrid.

After receiving a master's degree in child development, Abraham went for a diploma in special education at an institute managed by the Handmaids of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Mumbai. By then, "spirituality, discernment and mission became significant aspects of my life," she said. A year later, in 1983, she joined the Handmaids of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, but she left it after 22 years "with a heavy heart."

She talked with Global Sisters Report about her views on feminist theology and Catholic religious life.

GSR: Why did you leave religious life?

Abraham: As years passed, an ideological gap began building up in me with regard to religious life. The critical feminist sensibilities I had developed over the years made me see God, human relations, the church and mission in a different light.

When I took a feminist stand vis-à-vis the church, others cautioned and reminded me that I was a sister. It was as though my congregation's leaders had to answer for my stand. It reached a stage where I had to either conform or take a stand. I took the stand that justified my convictions.

Deciding to leave was not easy because I had developed deep emotional bonding with the congregation. The congregation loved me much and gave me many opportunities to know its mission in different contexts. I know many sisters personally. I had also spent a year in Chile and three years in Spain. With all this, quitting was a home-leaving experience, painful for me as well as for the sisters.

I should admit I have a grown a lot because of the opportunities and exposures the congregation offered me. At the same time, I too gave my best to the congregation through various responsibilities it had entrusted to me.

What have you done since you left religious life?

After leaving, I registered for Ph.D. in the Department of Christian Studies at the University of Madras, India. On finishing it, I joined a team that coordinated a project on leadership training for sisters. I also taught as guest faculty in the same department that did my doctorate. Later, I worked as a senior fellow of the Indian Council of Social Science Research for a project on gender education.

When asked, I teach feminism, feminist spirituality and feminist theology in some institutes of priestly or religious formation. I am also involved in some grassroots campaigns with women and youth.

I have been active in some national and international organizations related to gender justice, liberation theology and feminist theology. They are Indian Association for Women's Studies, Indian Women Theologians' Forum, Ecclesia of Women in Asia, World Forum on Theology and Liberation and Asian Lay Leadership Forum. I also work with ecumenical groups in Kerala on gender and environmental concerns.

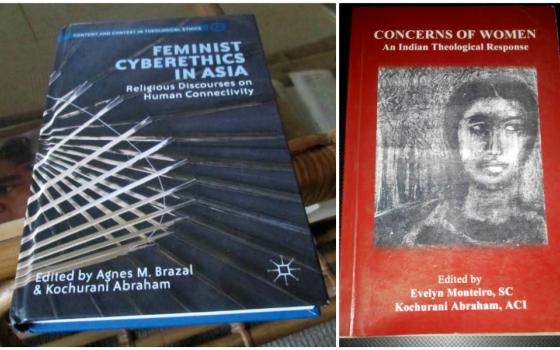

I also work on my first book based on my doctoral research. I hope to complete it in a few months. I also plan on writing a couple more books, particularly related to gender and feminist theology in the Indian context.

What is feminism and feminist theology? Please explain.

Feminism is the assertion that women are fully humans. This signifies that women have capabilities, feelings, needs and desires like other humans. They need equal opportunities for realizing their intellectual and spiritual capabilities. A feminist consciousness that affirms women's full humanity confronts all forms of gender or sexual violence women face.

Feminist theology is liberative. It corrects and completes the mainstream theology. It also critically examines and challenges the male-centered mainstream theology that sees the divine only in the form of male bodies or teaches that only such bodies can mediate with the divine for humans. It questions the legitimization of women's subordination by religion's hegemonic codes. It redefines Christian theology so that every aspect of Christian life and knowledge — Christian anthropology, ecclesiology, spirituality, sacraments, religious vows and the rest — is perceived and interpreted as inclusive, egalitarian and liberative. It advocates a liberative knowledge of God in all its implications for women and other marginalized groups.

How has the church hierarchy reacted to such views? Do you have any theological differences with it?

Yes, I do. My theological differences with the church are mainly because of the gendered ecclesiology on which the hierarchy is founded. This ecclesiology identifies men with Christ, the head, and women as the body that is subordinate and dependent. Such a system allows men only to exercise leadership at all levels.

What changes would you like to see in the church?

First, I would want the church declericalized. The church needs leadership, but the current hierarchical structure based on "priestly" ordination contradicts the spirit of the Gospel and model of Christian leadership. It is time for a serious rethinking on what it means to be the church today.

It is time we rethought the ecclesiastical traditions that support male priesthood and hierarchy. The transformation of the church with new structures of participation has become necessary if we want a new ekklesia that transmits the energies of the Spirit to the world today.

I want the church to be more democratic. Its worship and other matters should be led by people, who are imbued by the Spirit with sufficient preparation. Their gender — male, female or transgender — should not a hindrance. I also want the church freed of caste, class and gender politics to share power in mutuality so that it can truly be ushering in the reign of God.

Is ordination of women the answer?

This question presumes that I consider women's ordination to priesthood important. True, at one time, I did think women's ordination was important to make male-female relations in the church more egalitarian. But I do not share that view now. I don't believe ordaining women as priests will make a difference.

Anyone who has studied church history knows priesthood as we have in the churches today is a historical development. The Gospels show that Jesus did not envision a leadership founded on priesthood. In fact, he vehemently opposed the Jewish priestly tradition and the manner in which Jewish priests exercised power.

Pope Francis has promised a commission to study the diaconate for women. What is your response?

It is doubtful if the Vatican commission will come up with anything new. There has been a lot of work on this matter from the perspective of the Bible and the church tradition. Women, especially religious, already do many things that come under permanent diaconate without label attached to it.

Permanent diaconate is basically a ministry of service. It is a compliant ministry of service, where obedience is its hallmark. Our patriarchal system views service as essentially a woman's duty. As long as the current gender norms govern the church, female diaconate, if it ever happens, will only uphold a gendered ecclesiology in theology and praxis.

What is needed is not the incorporation of women into the lowest strata of the hierarchy, but the transformation of the whole church into diakonia [service]. Service is the heart of Christian spirituality and the eschatological hope for a society transformed in and through love.

Should the Vatican appoint women to its highest decision-making bodies?

Surely. It is high time the church evolved as a community that witnessed to gender justice and egalitarian relationships. If the church has to become a sacrament of the reign of God, it should have women, men and transgender persons sharing responsibilities at all levels. This means that women along with men should be at all levels of decision-making and in every aspect of ministry.

A mere token representation of women is not enough. It is important to have women at all levels of leadership for a healthy church. Women can bring their wisdom born of their experiences of life for the well-being of the church and its mission.

How do you view religious life today?

The present apostolic model of institutionalized religious life that began almost 500 years ago is breaking down. It will either die off or emerge in new forms. There have been clear signs of this transition in the West during the past few decades. It does not mean the institutional religious life has no future, but it will have a witness value only if it becomes prophetic.

We see individual religious and small groups who maintain their commitment through networking and participation in the struggle for justice, human rights and environment. These are new expressions of religious life. For example, the Leadership Conference of Women Religious of the United States. It stands for justice in the church and society. It promotes women's spiritual and theological assertions as expression of a prophetic religious commitment, despite coming under the church hierarchy scanner.

Such prophetic witnessing would take a few more decades to come to India and other countries in the global south, where institutional religious life still thrives. However, even in India, many live a committed life without congregational support or community life. Women like me with a feminist theological worldview are preparing the way for new forms of consecrated life. New expressions of consecrated life that respond to the current concerns and challenges will be prophetic and mystical. It may not be visible through powerful institution but will become a transforming presence like a leaven.

[Philip Mathew is a journalist based in Bangalore, southern India. This article is part of an ongoing collaboration between GSR and Matters India, a news portal that focuses on religious and social issues.]