Dolores Florez, 75, was skeptical the day she walked into a Las Hermanas retreat in Colorado Springs, Colorado. A divorce after 24 years in an abusive marriage had left her bitter and depressed. But her friend, Celia Vigil, persisted.

Florez told her friend she didn’t want to pray; she just wanted to be left alone.

“I was angry at God,” Florez said, but eventually she agreed to go.

“Las Hermanas really helped me to change my life and to give me back my dignity – to recognize my dignity and my worth as a Hispanic woman.”

Las Hermanas, which means “the sisters” in Spanish, pushed to end discriminatory practices in the Catholic church, especially toward Latina Catholic lay women and nuns.

Starting in the early 1970s, the organization founded by two women religious worked to increase educational and leadership opportunities for Latinas, advocated for more Latino bishops, exposed racism and fought for the right to work with Hispanics. Las Hermanas also played a pivotal role in the foundation of the Mexican American Catholic College in San Antonio that offers bilingual degrees in pastoral ministry.

“They not only mobilized women religious; they partnered with women in general, with Mexican-American Latina women who were on the front lines of social change in the late ‘60s-early ‘70s,” said Arturo Chávez, 53, president of the Mexican American Catholic College. “They were also important voices for change in the educational systems that they were a part of.”

Members in the organization saw education as one pathway to end discrimination that had relegated Latinas to less important jobs, according to Sr. Yolanda Tarango, 66, a Sister of Charity of the Incarnate Word who will speak about Las Hermanas at a symposium this week. As a result, members often encouraged women to pursue academic degrees.

”So they’d be a certified nursing assistant or vocational nurse, not likely to be prepared to be administrator of a hospital because they [church leaders] didn’t really believe you could do it,” Tarango said. “In education you might be the first grade teacher, but you were unlikely to be the principal.”

To combat this, members set up scholarships for Latin American nuns, who fared worse than American-born Hispanics, Tarango said, and often worked as cooks and housekeepers. The goal was to get them out of the “domestic sphere and into the pastoral.“

Education transformed Florez from an abused housewife to a leader of workshops on domestic violence. She recalled the first day she went to college. “My mind was like a sponge,” she said. “Las Hermanas was the group that helped me awaken to the possibilities in my life.”

Later she worked with women who had served time in prison and helped them improve their lives as well. Florez said she was president of Las Hermanas in Colorado for nine years and in 1985 was named Hispanic Woman of the Year by Hispanic Salute, a Colorado group that recognizes volunteerism.

Tarango was an original member of Las Hermanas, founded in April 1971 by Sr. Gloria Gallardo, a Sister of the Holy Ghost, and Sr. Gregoria Ortega, a Victory Noll Sister. And despite the successes the group would achieve, there were many obstacles in the early days.

Inspired by the activism of the Chicano movement and the momentum of Vatican II that modernized the church and made it more accessible, Gallardo and Ortega decided to hold a meeting in Houston with other sisters. But when they asked bishops for the names of sisters with Spanish surnames, Tarango said, “they got minus one percent response to their survey.” Eventually they appealed to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious and were able to get a letter out to all of those congregations in the United States.

At first the group struggled with issues of identity. As nuns left their orders, the group expanded to include lay women. Everyone could participate, but voting rights and leadership positions were reserved for Latinas born or raised in the United States. The idea was to address the fact that their minority status often lowered their self-esteem. “And so we were focused on those of us that were raised as a minority and what it does to our sense of self, versus immigrants who lack opportunity but have a clear sense of identity,” Tarango said

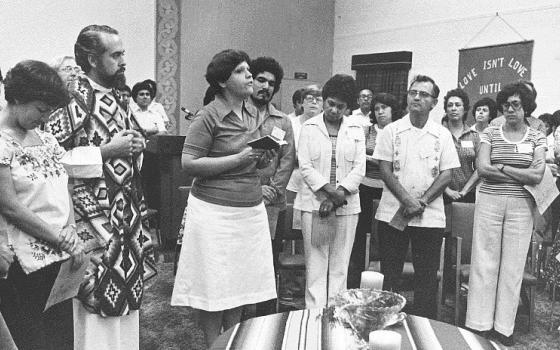

“Unidas en accion y oracion,” (united in action and in prayer) became the group’s motto. “We were very explicit that ‘accion’ came first and not ‘oracion’ because we didn’t want to be perceived as ‘las monjitas en oracion’ (the nuns in prayer),” Tarango said. “We wanted to highlight the activist part.”

Las Hermanas members quickly took on more activist roles by demanding the right to work with their own people.

Prior to 1970, Chicano and Chicana priests and nuns weren’t allowed to speak Spanish to each other or people they ministered to, according to Lara Medina, the author of Las Hermanas: Chicana/Latina Religious-Political Activism in the Catholic Church. “They themselves were required to drop their culture and their language at the door of the convent or seminary.”

“At the time, most of us were working in middle-class schools, not with Hispanics,” Tarango said. “We left that first meeting with a commitment to go back to our congregations with a demand to be allowed to work with Hispanics in the U.S.”

Vowing to focus on “the most vulnerable,” they started moving the church beyond its usual boundaries to where it had not been, such as in domestic violence shelters, immigration law offices and in the fields with farmworkers, Tarango said. “It was also about creating a new way of being ‘church.’”

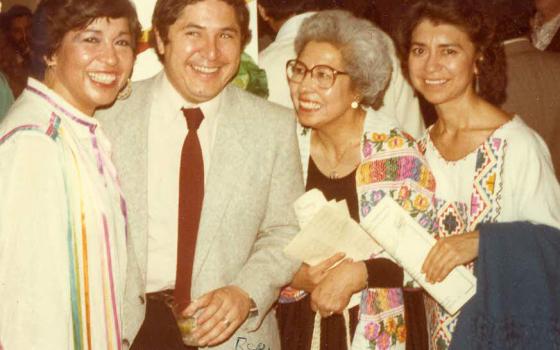

One of the most important accomplishments of Las Hermanas, according to Chávez, was its role in the establishment of the Mexican American Catholic College in 1972.

The college, formerly known as the Mexican American Cultural Center, was created to train lay people, priests and bishops, Chávez said. Currently the college partners with the University of Incarnate Word to offer bachelor’s and master’s degrees in pastoral ministry.

Seeking opportunities for Hispanic women to further their leadership skills was another goal. “In order to be a leader you have to have the opportunity to practice leadership,” Tarango said. So, Las Hermanas members pushed to get Latinas on boards, committees and in congregational leadership.

That opportunity came for Celia Vigil, Delores Florez’s friend, in 1980. Las Hermanas organizer Josephine Zamora approached her about pursuing a new position as director of the Office of Chicano Affairs in the Denver archdiocese. “I don’t know if I can do that,” Vigil said. She was working as a customer service representative for the IRS.

“’You can do it, you can do it,’” Vigil said, recounting Zamora’s words. “She encouraged me, she helped me put my resume together . . . before I knew it, I was hired.”

In a move to increase Latino church leadership, Las Hermanas teamed up with the Latino priests’ group, PADRES, to circulate a petition asking for more Hispanic bishops.

“That’s one thing Las Hermanas has been known for, that they tried to build bridges, for example, working with men, working closely with men, not against men,” Chávez said.

Tensions sometimes surfaced between the two groups as they tried to assert leadership, Tarango said, but “we were willing to work with that tension in order to do what we needed to do.”

Their efforts got attention, and the number of Latino bishops rose from one in 1970 to 21 in 2000, according to the Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops lists 28 Hispanic bishops in the U.S. Catholic Church on its website today.

A key Las Hermanas contribution in the intellectual world was “mujerista theology,” a phrase coined by member Ada María Isasi-Díaz. She and Tarango authored the book, Hispanic Women: Prophetic Voice in the Church, that gave rise to the theology.

“It’s a theology that is rooted in, first of all, liberation – liberation from oppression – but also at the same time rooted in the distinctive perspectives of women as Latinas,” said Adrienne Nock Ambrose, 50, an assistant professor of religious studies at Incarnate Word University.

As Hispanic Catholics gained more representation in the church and were treated more equally, Las Hermanas shifted its focus. “I think from ‘85 on it was to bring together real grass-roots women who had never had the opportunities,” Tarango said. The group also evolved from working nationally to focusing more at the regional level. “If there were any action strategies, they were pursued locally and not nationally.”

While the group took on a more “intergenerational approach” in 2003 and focused on broader social issues such as human trafficking, sexual abuse and the environment, Tarango laments that their numbers dwindled. “And part of that is that we were getting older as an organization and as a group.”

The loose structure of Las Hermanas – it didn’t collect dues – did not allow for precise membership counts, but Tarango estimates that they had around 900 members at the organization’s peak in the mid-‘80s. She hesitated to give a current estimate, simply because she doesn’t know. Many regional groups have faded away, she said, leaving those in Texas, Colorado, New York and California as the most active.

But Tarango hopes the upcoming Las Hermanas symposium at University of the Incarnate Word will lead to another national meeting. “We really need to come together again,” Tarango said, “and really look at ‘What do we need to be for the 21st century?’”

Mujerista theology has also sparked renewed interest. “Isasi-Díaz really started a whole intellectual movement as well as Las Hermanas,” Ambrose said. “When she passed away a few years ago, there was a tremendous amount of interest in her work, and lot of young energetic Latino and Latina scholars kind-of drew upon her work.”

And it is these new Latino and Latina scholars that Medina hopes will “restart the organization, reinvigorate it.” Las Hermanas has not had a national conference since 2007, even though there are still many pressing issues for Latina women.

“One of the things with Las Hermanas is to recreate that passion among all the successful Latinas to really look at what are you doing about your sisters,” Tarango said. “Until the most oppressed woman is free, none of us are.”

[Nuri Vallbona is a freelance documentary photojournalist who has focused most of her career on social justice projects such as modern-day slavery, inner-city poverty and crime. She worked for the Miami Herald from 1993 to 2008, has won a number of awards and is a former lecturer at the University of Texas and Texas Tech University.]

Click here to learn more about “Las Hermanas, the Struggle is One” a symposium March 19-21 at University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio that will highlight the group’s 44-year history, its impact on Latina Catholics, its role in fighting discrimination in the church and its establishment of mujerista theology.