Marie Racine was well established, a software engineer for 17 years, when something happened.

“We had a meeting, and all of the sudden when they introduced the new projects, I just wasn’t interested anymore,” Racine said. “It just no longer mattered to me.”

That awareness propelled Racine onto a new path — and into an emerging trend about women committing to religious life: Racine entered a Benedictine monastery the day before her 40th birthday and made her final vows seven years later, in 2007.

Little attention was given to the age of women professing final vows until a 2009 study for the National Religious Vocation Conference reported that 91 percent of women religious were age 60 or older. Researchers at the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), who conducted the study, knew they needed to look more closely at what was happening.

“It’s just something that wasn’t studied until we saw it changing,” said Dominican Sr. Mary Bendyna, one of the researchers.

CARA began issuing a report each year, starting in 2010, on the profession class of that year — the men and women making final vows.

It was already clear that fewer women were joining religious life, making the average age of women in religious life higher and higher as they got older in a time when fewer and fewer young women were joining. But CARA data also showed that women professing final vows were themselves older — much older — than before. (CARA tracks those taking final vows, as the length of time between candidacy and final vows can vary greatly, though the average is about six years.)

In 2010, 47 percent of women professing final vows were aged 40 to 59. Another 26 percent were between 30 and 39. The median age for the class was 44.

Those numbers have steadily changed in the years since, reflecting an increase among younger women: By the class of 2014, only 27 percent of women taking final vows were aged 40 to 59 and those younger than 30 had increased from 18 percent to 25 percent. The median age of the class had dropped to 35.

But 75 percent of the class was still 30 or older.

Who are these women deciding later in life to become sisters?

Racine, now Sr. Marie Therese Racine, had thought about becoming a sister when she was a child and a teen, but it was at a time when sisters and priests were leaving religious life so she thought it wasn’t for her. In her late 30s, she was thinking about teaching or working in a parish, since she had been in music ministry most of her life.

Then a Franciscan sister she knew asked her if she had ever thought about religious life.

“I laughed her off, but as the days went on, her question kept nagging me,” Racine said. “It got disruptive.”

Two years later, she was part of the community of Sisters of St. Benedict at Our Lady of Grace Monastery — a decision that, while it was difficult to leave a professional life and friends behind, was made easier by the maturity and clarity of age, she said.

“I’m not sure I would have had that same thing when I was younger,” Racine said. “If you had asked me when I was 25 or even when I was 30 or 35, I would have had no idea I would be here.”

Sr. Margarita Walters, a Benedictine Sister of Chicago, professed her final vows at age 60.

For Walters, joining religious life in her later years wasn’t difficult: She had been considering it since eighth grade. But as so often happens, life got in the way.

“I was a pretty girl and liked boys. The next thing I knew, I was married and had kids,” Walters said.

She raised her family and had a successful career in sales and administration. And when her husband died, there was really nothing left to stop her.

“The stuff here isn’t lasting. You can stockpile stuff, but it’s just things. I was looking for something that would last,” Walters said. “I found it much more compelling to meditate and pray and do things for other people.”

Sr. Juliann Babcock, former prioress of Racine’s Benedictine community in Beech Grove, Indiana, said that while the experience and education older recruits bring is valuable, they also have something which is harder to describe, something that comes from having spent decades in the secular world, seeing what it offers, and then choosing something different.

“They’re very intentional about religious life,” Babcock said. “We also see a great desire in these women to serve. They’ve had these successful jobs, but money isn’t the answer. They’re happier in these roles of service.”

How pervasive is the trend? Some communities are marketing to it.

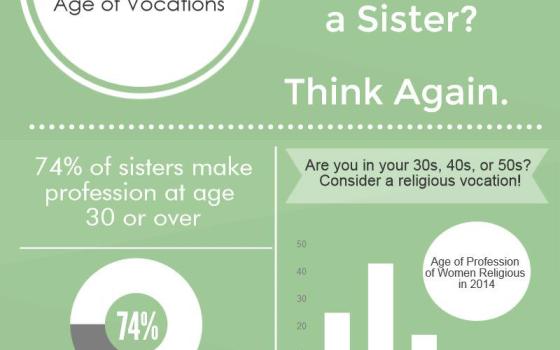

Nicole Sotelo, communications coordinator for the Benedictine Sisters of Chicago, created a graphic using the CARA data and shared it on Facebook. “Think you have to be in your 20s to become a sister?” the graphic asks. “Think again.”

The graphic points out that 74 percent of sisters made their profession at age 30 or older, and says, “Are you in your 30s, 40s or 50s? Consider a religious vocation!”

Sotelo said it was shared so widely by other communities that it became one of the most shared items she had created.

Babcock said many of the older women who come to them are looking for the community that religious life offers.

“We find members are looking for that support, that prayer, that community of people who share values,” she said. “We hear, ‘I feel like I’d grow more in my spiritual life if I had people to talk to and share with.’”

That community is also key for many younger sisters.

Franciscan Sr. Sarah Kohles, a core team member at Giving Voice, a peer-led organization supporting younger women religious, said there is often an age gap that can make younger sisters feel isolated. That makes connecting with other sisters who understand the feeling even more important.

“The age gap in religious life is one of the most challenging aspects of religious life for young women,” said Kohles, a Sister of St. Francis of Dubuque, Iowa. “Connecting with other ‘young nuns’ has been as essential for me as my own Franciscan community because these women are my peers. They help me know how to be a religious in my 30s.”

Of course, along with their experience and education, women often bring other things with them to religious life, including student loans that need to be paid off. A 2012 CARA study found that about one third of religious institutes (for both women and men) reported that about one in every three of the serious inquirers coming to them had student debt — an average of $28,000 each. Seven in 10 institutes turned away at least some inquirers because of student debt.

On the other hand, younger inquirers without debt may also not have the college degrees many communities want, so they may end up paying for her education anyway.

“We deal with it on an individual basis,” Babcock said. “It depends on the individual.”

Older sisters may have experience and maturity, but younger sisters have an energy and vitality that’s difficult to match. Babcock said communities need both.

“There’s gifts in both,” she said.

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. Follow him on Twitter @DanStockman or on Facebook.]