In the last decade, student loan debt in the United States has become a nearly inescapable problem. Experts now use words like "staggering" and "crisis" to describe the fact that some 40 million adults in the U.S. carry college debt to the collective tune of a record-breaking $1.2 trillion.

And the numbers are only climbing.

Case in point: A recent Brookings Institution study found that between 2004 and 2012, not only did the number of students borrowing for their education increase by 70 percent, so too did the amount the average student owed. Another independent research group, the Institute for College Access & Success, found that 69 percent of college seniors who graduated from a public school in 2014 did so with education debt. And these debts were no small potatoes; the average borrower owed almost $29,000. That's the cost of a small luxury car.

Given the pervasiveness of student loan debt today, it's not surprising that such debt has started to have a noticeable effect on postgraduate vocations — a fairly new phenomenon. After all, some 60 years ago, it was commonplace for a woman to enter the convent right out of high school, her community then paying for her post-secondary education. In fact, in those days, a vocation was one of the sure ways a woman could get a college education.

But today, most — if not all — women come to religious life with at least one degree already under their belts, which means they are also bringing their financial baggage with them into the discernment process. Yet many religious communities simply cannot afford to take in candidates with large student loan debt.

Leaving school with tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debt has long-reaching implications for all graduates, said Kristan Venegas, a research associate who studies student debt at the University of Southern California's Pullias Center for Higher Education.

Even students who aren't thinking about religious life are "delaying buying homes and going to graduate school," she said. "They're delaying starting their families because they have student loan debt that they want to pay down or pay off before they invest in a mortgage or any sort of long-term indebtedness."

For young women who are considering religious life, student debt can be equally stifling, often leaving them forced to either delay their vocation or walk away from it altogether.

Take Amanda Stueve, for example, who has been waiting for about a year to join the Little Sisters of the Lamb in Kansas City, Kansas. Stueve, 27, graduated from Texas A&M University in 2013 with a master's degree in international affairs and $58,000 in student debt. The Little Sisters of the Lamb can't afford to absorb her debt, and Stueve, who has yet to land a job in her field, can't afford to pay it off right now. And so she waits.

Stueve calculates that once she gets a job with the right salary — and if she's aggressive — she could pay off her loan debt in three years. It's a sticky situation, but she laughs about it. She's convinced that God wouldn't have placed a call in her heart only to make it impossible to fulfill. And it helps, she adds, that the Little Sisters of the Lamb have been supportive.

"They know that I'm discerning, and they're basically willing to take me in any time that I'm debt-free," Stueve said.

Until last month, Stueve had been living in nearby Gardner, Kansas, working as a nursing assistant and applying to international relations jobs. When the sisters recently offered to let Stueve move in with them and start taking some formation classes, she gladly took them up on the offer. Still, Stueve's financial situation leaves her formal status with the community somewhat uncertain; she's not sure that she'll be able to take any steps past these few initial formation classes.

"I definitely couldn't be a postulant with the debt," she told Global Sisters Report.

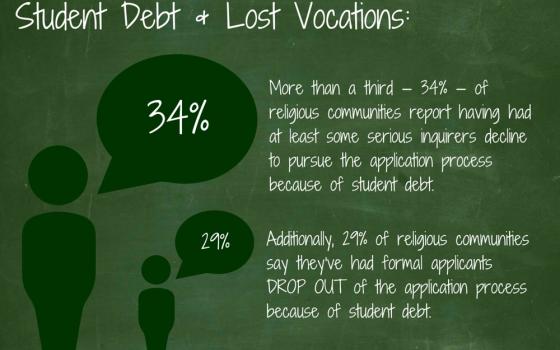

Stueve's situation isn't all that unique. In the last few years, more and more religious communities have come to realize the chilling effect student debt can have on the vocations of young would-be religious. In fact, by 2011, the situation had become so conspicuous that the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate and the National Religious Vocations Conference teamed up to find out just how much of an impact student debt was having on vocations.

What they found was that 4,328 discerners who contacted a religious community in the period between 2001 and 2011 had student debt, with an average debt amount of $28,000. Furthermore, in that same period, 69 percent of religious communities that had been contacted by at least three serious discerners said they had turned someone away because of his or her student debt.

Basically, said Mark Teresi, executive director of the National Fund for Catholic Religious Vocations — an organization that grew out of the joint CARA and NRVC study — in the last 10 years, more than 1,000 vocations have been lost to student loan debt. (Note: The National Fund for Catholic Religious Vocations is funded in part by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, which also funds Global Sisters Report.)

The student debt situation is a crisis for the country and the church, Teresi said, but he added that for the church at least, it's also easily fixable. It's simply a matter of mirroring for prospective candidates what the church has already put in place for older religious.

"On the back end, we have the collection for the retired religious, and it's the most successful collection in the history of the Catholic church in the United States," Teresi said. "What we don't talk about are our religious on the front end — those 1,000 candidates that would have entered if they didn't have college debt."

The National Fund for Catholic Religious Vocations helps religious communities take in candidates with significant college debt by offering grants that cover that debt. This past summer, the organization gave out its first 10 grants — a total of $213,000 to eight communities of women religious. Teresi said the organization plans to give out another set of grants next year, this time to communities of both men and women religious.

Other Catholic groups are also exploring ways of removing the obstacle of student debt for religious discerners. The Mater Ecclesiae Fund for Vocations, for example, also gives out grants to cover candidates' loan debt. Meanwhile, the Minnesota-based Labouré Society (also funded in part by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation) helps religious candidates pay off their student debt by teaching them fundraising skills.

In the latter model, candidates accepted into the Labouré program are grouped into classes and, after the intensive fundraising training, they work together to raise funds for the entire class. The candidates are encouraged to spend at least 10 hours a week fundraising in addition to keeping up with whatever employment they had before joining the program. The candidates don't pay fees or interest to the society, although they are responsible for their monthly loan payments during the fundraising process.

After six months of fundraising, an award from the class fund is granted to candidates based on a review of their individual efforts. Then, once candidates enter formation, the Labouré Society helps cover their monthly loan payments for three years. At the end of the three years, the Labouré Society pays out the remaining award balance.

When 27-year-old Sr. Gabrielle Bibeau, now a novice with the Marianist Sisters, needed help paying off the last of her $60,000 in student loan debt, she turned to the Labouré Society.

Bibeau was already interested in exploring religious life when she graduated from the University of Dayton in 2011 with a bachelor's degree in English and religious studies. So to pay down her student loan debt, she moved back home with her parents and worked in her home parish for three years. Just in case.

In those three years, Bibeau was able to cut her loan debt in half. After applying for pre-novitiate with the Marianist Sisters in 2013, she teamed up with the Labouré Society to raise the money to cover the other half of her debt. For six months, she wrote letters to potential donors in addition to speaking at churches to solicit support. In the end, she raised $26,000 with the Labouré Society, and her family held a fundraiser for the remaining $4,000.

Bibeau told GSR that groups like the Labouré Society have the potential to change the negative prognosis many Catholics have for religious life.

"A lot of people think that no one's being called to religious life anymore," Bibeau said, "which is not true. There are people who are called to religious life who just aren't able to do it."

She could have been one of them.

For Bibeau — and for most students in the United States these days — taking on student loan debt is not optional because college tuition is increasing at vertiginous rates. According to Bloomberg News, the cost of college has increased 1,120 percent since 1978. On average, it now costs more than $17,400 a year to attend a public, four-year institution in the United States. Even the average public, two-year program costs almost $9,000 a year.

"I needed to borrow money to go to school. Period," Bibeau said of her time at the University of Dayton, which currently costs $19,545 a semester. "I come from a working-class family, and my parents couldn't afford to help at all with my education. So I really had to take out student loans."

Even Stueve, whose first year of undergraduate studies at Kansas State University was covered by scholarships, eventually had to take out loans to study abroad — something she deemed necessary to fulfill her then-dream of becoming an international diplomat.

In the last eight years, a number of bills aimed at addressing the student loan debt situation have been introduced in both the U.S. House and the Senate, but it seems unlikely that religious communities will benefit from any of them. In an email to GSR, Jesuit Br. Lawrence Lundin*, associate director of administration and finance for the Resource Center for Religious Institutes, said even established programs that forgive loan debt for teachers and public servants aren't a great help to religious congregations.

For starters, these programs require that payments be made on a loan for 10 years before it is forgiven — which may or may not be financially feasible for a given congregation. Furthermore, the debtor's employment cannot include any religious instruction or worship services. So if religious communities are waiting for debt-free candidates — or candidates whose debts could soon be forgiven — to start knocking on their doors, it appears they are waiting in vain.

Bibeau said the Marianist Sisters recently began a lay-supported fund specifically for future candidates' student loans, and she encourages other communities to be proactive in addressing student debt.

The National Fund for Catholic Religious Vocations' Teresi would probably agree. He recalls meeting a young woman last year at the Festival of Faiths who told him she has wanted to be a Catholic sister since the fourth grade. As she was leaving the booth where he was exhibiting, he said she leaned over and said to him, "Mr. Teresi, there are a lot of us out there."

Bright and talented future sisters are out there, he told GSR, and the church needs to be doing everything it can to make sure they are able to follow their vocations. And right now, student debt is one of their major obstacles.

Stueve said if she could have foreseen where God was leading her — not to mention the economic recession that would hit in the middle of her college career — she would have borrowed differently.

However, it wasn't until she was in graduate school that she felt called to religious life, and by that time, she'd already taken out more loans on top of the ones that had funded her undergraduate study abroad. She just didn't see how she could be both a full-time master's student and a full-time employee who made enough to cover the tuition at Texas A&M, which is currently $11,348.16 a year for an out-of-state graduate student.

Still, Stueve doesn't have any regrets, and she offers this advice to other young women who may be juggling the need to finance their education with a possible vocation:

"Pray often so you can be open to God. But don't close yourself off from opportunities in your academic and career path because you may, someday, want to become a sister," she said. "If you need to take out the loans for a valuable experience like study abroad, do it. And trust that God will make a path for you."

*An earlier version of this story misspelled Lundin's name.

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is Global Sisters Report staff writer, based in Kansas City, Missouri. Follow her on Twitter @dawn_cherie]