There are many kinds of pioneers, and the Sisters of St. Ann demonstrate this superb diversity. Since their founding in Quebec, Canada, by Blessed Marie Anne Blondin in 1850, their original spirit continues vigorously today.

Four sisters and a lay woman made the two-month ocean voyage down the Atlantic coast, became some of the first women to cross Panama by train before the canal, then sailed north along the Pacific coast, where the bishop of Portland wanted them to serve in his diocese. The sisters had committed themselves to the bishop in Victoria, so in spite of the attractions of Portland, house and all, they continued on. Their 1858 arrival in British Columbia coincided with the Fraser River Gold Rush, and their original goal of educating indigenous children expanded dramatically. A small fort inhabited by 150 people had grown to a city of as many as 20,000.

It apparently didn’t faze them that the frontier was raw, the population was exploding and the demands for services skyrocketing. In a 30-by-18-foot log cabin, sisters briskly arranged their mattresses on the floor, chopped firewood, hung their aprons over the windows and, within two days of their arrival, started teaching catechism. Never easily intimidated, they focused on educating the whole person and, when the regular school year began, included the arts in the curriculum of their one-room schoolhouse.

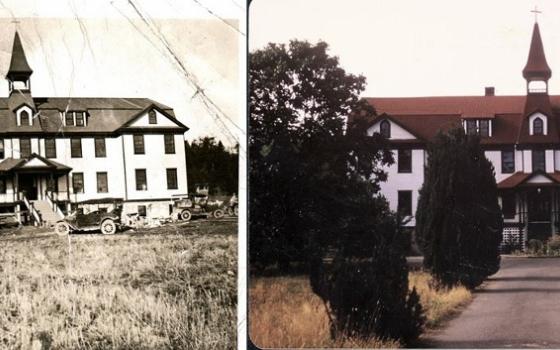

By 1870, 51 students were enrolled, and despite dirt streets and primitive conditions, a series of teachers who were artists themselves focused on beauty and creativity. Their St. Ann’s Academy (where more than 36,000 students had studied by 1973) was the first in the area to offer art education − and the only one to continue it for 114 years. Interestingly for that era, many of their creations didn’t focus on religious subject matter; their floral china-painting, for instance, was a profitable fund-raiser. More than a frivolous extra-curricular activity, art bridged social, religious, racial and age divides, strengthened imaginations and linked the sisters to the larger community.

On a frontier, people have the freedom to do things differently and break through boundaries constraining “what sisters are supposed to do.” So, with fresh fruit and vegetables in short supply, the sisters grew their own food, hired doctors and teachers, served as architects themselves, and became self-sufficient in tough circumstances. At a time when most women depended on men economically, socially and politically, they made their own decisions. For example, because of legalities, Mother Mary Providence bought property in her own, not her religious community’s name and oversaw four schools and administered a hospital − at the age of 22.

A daring and visionary superior, she said, “A woman’s influence is not limited; life will be mostly what women truly wish it to be.”

It’s not surprising that by the 150th anniversary of the sisters’ arrival in Victoria (2008), Kim Campbell, the former prime minister of Canada and the first female in that role, said that a direct line ran from her education at St. Ann’s Academy − where “women ran the world” − to her government office.

“I learned from the sisters that women could do anything!”

Indeed, at their pinnacle, 300 Sisters of St. Ann worked throughout British Columbia, Alaska and the Yukon, efficiently running their institutions: St. Ann’s Academy, St. Joseph Hospital, other schools and hospitals, and the 400-acre Providence Farm. In 1867, Sisters of St. Anne from Quebec accompanied French-speaking families to the textile mills of the Northeast United States, and their strong presence in the U.S. continues.

Fast forward to 2014.

Sr. Marie Zarowny, province leader in Victoria, faces the challenge of closing it all down in a way that honors the legacy of the pioneers, bringing their work to fulfillment. She examines the motivating principles and tries to continue the work, though it won’t necessarily carry the SSA name in the larger community. Thirty-eight sisters remain in Victoria, many of them retired or living at Mount St. Mary care center.

Despite reduced numbers, the active members are a gutsy bunch, quick to challenge, question, explore, laugh. They work with Reiki, eco- and restorative justice, or in prisons, help people with addictions, combat human trafficking, do fundraising or spiritual direction with the same vigor they once ran a nursing school (1901-84). One would never associate the word “diminishment” or “despair” with this lively group.

As on previous frontiers, they are immersed in the larger community, (84-year-old Sr. Lucy DuMont is the longest marathon walker and fundraiser for Mount St. Mary). Their current work of dismantling will, in the long run, be a gift to all British Colombians, of whom only 10 to 15 percent are Catholic.

As Sr. Sheila Moss said in her 2012 address on the 150th anniversary of the city of Victoria: “We collaborate with the people and institutions of Victoria, preserving valuable memories from the city’s founding years and supporting current projects that continue the legacy and values of the sisters.”

The archives containing historical documents, photographs, artifacts and art, carefully maintained by the sisters from the early days to the present, have been moved into the British Columbia Archives. In addition, the first log schoolhouse, now part of the Royal BC Museum, has been restored as a site for many visitors and school field trips.

Further putting the philosophy into practical terms, the sisters deposited 18 paintings to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, honoring “the historic role of women as artists.” The deposit includes “Wild Lilies” by Emily Carr, a world renowned Victoria artist. The sisters cared for Emily’s sister, Lizzie, who had breast cancer, until her death in 1936. In gratitude, Emily gave the sisters the painting, which they also allowed to be used by the Breast Cancer Society for fundraising to enhance awareness and research.

In one of her greatest challenges, Zarowny headed the Task Group of Catholic Organizations involved in the historic Indian Residential Schools, contributing to a major settlement agreement involving all churches, the Canadian federal government and First Nations. She summarized this sensitive and honest work in a presentation during the visit of Canada’s First Nations and representatives of the Canadian Catholic Church with Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican on April 30, 2009. In tribute to their long-standing friendships with the sisters, Inuit elders in Alaska who heard about the Vatican’s investigation of sisters told their bishop, “If the sisters hadn’t been here, we wouldn’t be here.”

Another remarkable transformation came to the farm purchased in 1864. A boarding school for native girls until 1876, it was enlarged to house orphans, then became a day school for more than 100 students. It closed in 1964 and moved its teaching down the street. But what to do with a 400-acre farm? Pioneering genius invited collaboration between the sisters, local nonprofits and government agencies. By 1979, they established a registered charity named the Vancouver Island Providence Community Association (VIPCA) in memory of Mother Mary Providence, mentioned earlier. The site became known as Providence Farm.

In 2009, at the celebration of Providence Farm’s 30th Anniversary, the sisters formally gifted the property to VIPCA. It operates today as a working, therapeutic, organic farm serving adults and seniors with mental health challenges, developmental and intellectual disabilities and age-related illnesses. Their motto says it all: “Take a deep breath and you’ll find the air is healthy; the work, worthy; the place, happy.”

It’s based on the belief that caring for the land together is, by nature, healing and therapeutic. Innovative programs provide jobs for those who’ve never been able to work before: in the areas of horticulture, art, woodworking, nutrition and textiles. A retail outlet sells their products, and a hearty communal lunch climaxes each day.

In the fall of 2014, the SSA Social Justice Committee led Peace Quest Victoria with project coordinator, Julie Cormier, engaging faith communities, Catholic schools and Victoria-based peace organizations to mobilize around peace, non-violence and reconciliation. Highlight of this project was the Puppets for Peace parade, which drew participants from around the world.

Needs change and responses differ. Both creatively pioneering and honoring tradition, the Sisters of St. Ann are like “the householder who brings out from the storeroom new things as well as old.” (Mt 13:52).

[Kathy Coffey is the author of several books about prayer, as well as catechetical resources and numerous articles in Catholic periodicals including National Catholic Reporter. She gives national workshops, retreats and conference speeches and taught for 15 years at the University of Colorado, Denver, and Regis Jesuit University. Visit her website.]