For 30 years Sr. Consuelo Morales, founder of Citizens in Support of Human Rights A.C. (or CADHAC), has been fighting on behalf of families whose loved ones have been kidnapped, killed or forcibly disappeared as a result of drug violence in northeast Mexico. (Courtesy of Consuelo Morales)

One Sunday afternoon in July 2010, Enrique, a 20-year-old law student, decided to go out for a walk and enjoy the mountain views.

"I'm going to take some pictures, and I'll be back in time for dinner," he told his mother, Laura (name changed).

"That was the last time I saw my son," she said.

Later that night she received a phone call, informing her that her son had been kidnapped for ransom.

The kidnappers warned her if she didn't follow orders, her son would be delivered in garbage bags. In desperation she agreed, emptied bank accounts, and sold everything she owned.

A few days later, Laura, then a 40-year-old kindergarten principal, took the money to a supermarket parking lot late at night, as instructed by her son's captors. Laura handed over the money to the kidnappers, who assured her they would return her son alive.

Hope turned into desolation for Laura. "I waited, from 11 in the evening until 9 in the morning just standing on a corner, numb," she told Global Sisters Report. "The criminals never returned our son to us."

Since 1970, Sr. Consuelo Morales has worked on supporting victims of kidnapping, forced disappearances, and torture, the families of murdered police officers, and the wrongly incarcerated in Nuevo León state. (Courtesy of Consuelo Morales)

Laura went home and locked herself in her room. "I fell into a dark void," she said. "I neglected my home and my two daughters," who then dropped out of college. Her husband, inconsolable, ceased working.

Days passed not knowing of her son's fate. She looked everywhere for Enrique, who loved to study and spend time with his grandmother, cooking and making her laugh. "I went to all the police stations and hospitals I knew; morgues, the federal police, the marines — and no one cared to even listen," she lamented. "I never found him."

Amid the bureaucratic chaos and the uncertainty of not finding her son, she was told to look for Sr. Consuelo Morales. "She is the only one who can help you," the prosecutor's office told Laura.

Advertisement

Morales, a member of the Canonesses of St. Augustine of Notre Dame congregation with a postgraduate degree in criminal law, is among the most prominent human rights defenders in Mexico; her work has been recognized by the International Criminal Court.

More than 30 years ago, Morales, together with other women religious, founded Citizens in Support of Human Rights A.C. or CADHAC, a nonprofit civil association in Monterrey and an apostolate of her congregation. CADHAC is the first center to promote and protect human rights in northeast Mexico.

Since founding CADHAC, she has been providing legal and psychological assistance to the relatives of the missing or kidnapped. As of September, disappearances in Mexico have reached more than 110,000 since 1967 (the year the National Search Commission began counting), with the vast majority occurring after 2006, when then-president Felipe Calderón launched Mexico's war on drug cartels. Monterrey, Nuevo León — Morales' hometown and the most industrialized city in the country — is a region particularly ravaged by drug cartels, corruption and criminal violence.

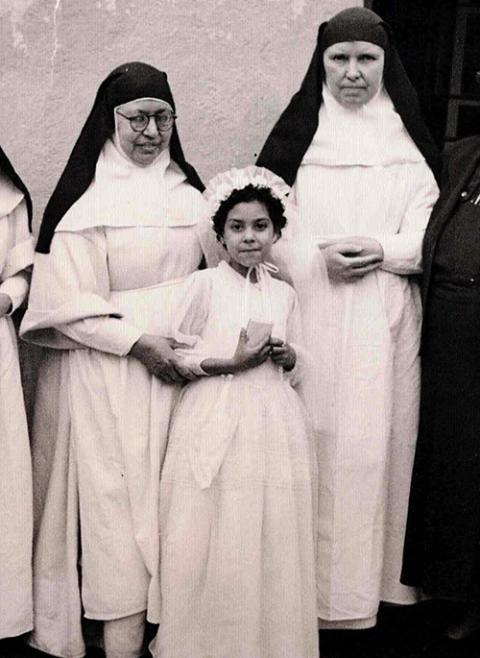

Morales during her first Communion in 1956. At the age of 10 she began to teach catechism classes and later volunteered with the Missionary Catechists of the Poor in Chipinque, Nuevo León. (Courtesy of Consuelo Morales)

And in Nuevo León, Morales said, missing persons are on the rise — and getting younger. Before, victims were between the ages of 18 and 28; now, they're children around 8 and 10 years old, and Morales' worry is that they're subjected to human trafficking.

"Working for human rights, for the dignity of our brothers and sisters, against injustice is working for the kingdom of God," she told GSR. "Trying to lighten the load of the people who suffer the most is working for the kingdom of God."

For three decades, Morales, the center's director, has accompanied thousands of women through the via crucis of reporting their missing relatives and publicly pressuring government officials and state and federal authorities to find them.

Just like the thousands of women whom Morales has assisted, Laura walked into the doors of CADHAC disheveled, hopeless and heartbroken.

"Our motto is that no one leaves CADHAC if they're not in a better condition than when they arrived," Morales said. "Although the victims, from a legal point of view, may no longer have possibilities, people have to emerge with a different attitude and hope."

In 2015, Mexican-American film director Bernardo Ruiz highlighted Morales' humanitarian work in the documentary "Kingdom of Shadows," on the harrowing effects of the U.S.-Mexico drug war. "There was a lot of chaos around her, but she always had intelligence and compassion. An ability to remain calm in a context of terror that I’ve never seen," the filmmaker told GSR from New York. Recalling Morales accompanying the pain of a woman whose daughter had been murdered, he said "that moment will stay with me for the rest of my career." (Courtesy of Bernardo Ruiz)

Laura, who has received legal counsel and group therapy at CADHAC for 12 years, recalled the first thing Morales said to her: "You are not alone. It's not your fault. … You have to get up, keep looking for your son and demand justice."

Morales, Laura said, "lifts us up with her kind words, teaches us about faith, to regain trust, provides us with courses on law and psychology and human rights at no cost, so we can talk to lawyers and police and demand to find our children," as CADHAC staff and attorneys accompany the families in filing reports and reviewing legal documents.

Victims in Mexico are reluctant to report the disappearance of a missing person to the police or the public ministry for fear of revictimization and criminal retaliation.

"Sister Consuelo knew how to support people who were looking for their relatives; people didn't know what to do, where to look, and Sister Consuelo made it possible that legislation was passed to have a local search commission," said human rights attorney Sofía Velasco, referring to the 2015 General Law on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes concerning Missing Persons.

Morales in August 2011 with a group of mothers of victims in front of Nuevo León's Governor's Palace in Monterrey. This was the first year in which the International Day of Victims of Enforced Disappearances was commemorated around the world. (Courtesy of Consuelo Morales)

At 75 years old, Morales' mission continues — and she isn't slowing down: Her organization serves 40 victims' families in dire need of a support system per week, with no institutional or government support.

Morales' latest effort is to implement the Amber Alert on all cellphones throughout Mexico, an effort that the legislature approved more than a year ago. With the immediate notification that someone has disappeared or been kidnapped, authorities would ideally be able to find that person swiftly, she said.

"However, government officials have not sat down to solve this serious problem," she said with great frustration, adding that a lack of agreement between officials and telephone companies has stalled the effort.

"We want to stop disappearances, as it generates continuous impacts on families," Morales said. "A missing person breaks the family project."

"We're living in an environment where it seems that God's plan is not possible, that life for dignity, for respect for harmony, for goodness is not possible," Morales told GSR in her Monterrey office. "Violence keeps growing in Mexico, impunity increases, and authorities and civil society don't put a halt to it and say, 'No more disappearances, no more dead women, no more missing children.' " (Julieta Valdez)

'You have to get up and rebuild your life'

Tanya Gonzalez, 34, has been searching for her missing husband since March 2013. He disappeared without a trace when he was coming home from work as a telephone technician in neighboring Tamaulipas, a state rife with drug and gun violence.

"He called me to tell me he'd be home before night fell," she said. "I never heard from him again. It's as if the earth swallowed him."

The road where Gonzalez's husband Felipe, then 26, disappeared is now called the "highway of terror" due to the hundreds of documented cases of kidnappings. With its many mountain trails and dark narrow paths, this region of the border with Texas is a strategic area for the illegal trafficking of drugs and people to the U.S.

"Sister Consuelo to me is an angel," Gonzalez told GSR one afternoon at the CADHAC center, awaiting her group therapy session that Morales leads, where roughly 40 women hold a prayer meeting for the victims and study the Gospel, while their children receive professional psychological assistance.

Sr. Consuelo Morales in May 2023 speaks before the Group of Women Organized for the Executed, Kidnapped and Disappeared in Nuevo León, or AMORES, where every week they share their stories, judicial updates on their sons and daughters cases and pray and reflect on Bible passages. (Courtesy of Consuelo Morales)

Women come from all over the state to attend the weekly meetings, usually beginning with the Group of Women Organized for the Executed, Kidnapped and Disappeared of Nuevo León (or its Spanish acronym AMORES) and ending with Morales. Some ride the bus or drive for several hours to meet with Morales.

"The first time I met Sister Consuelo, I was broken down," she continued, adding that Morales saw her every day with her kids, who at the time were 2 and 6 months old. Gonzalez recalled Morales telling her, "Are you always going to be in a sea of tears? You have to get up and rebuild your life. You have to get up for your children."

"I had no money, and Sister Consuelo made sure my children ate every day; I'll never forget that," said Gonzalez, who has since remarried and opened a clothing store.

Morales said one of the challenges in her work is mitigating the guilt that parents feel when their children have disappeared: They cease to celebrate birthdays, weddings, Christmases. In reminding the families of the violence and ruin that the captors have inflicted on their families, Morales also tells them, "Every time you don't celebrate a birthday or Christmas, you are allowing the violence to continue inside."

Morales and the group AMORES are pictured Aug. 30, 2015, during the International Day of Victims of Forced Disappearances. Every August mothers of victims, along with Morales, march throughout downtown Monterrey and meet in front of the Nuevo León's Governor's Palace to demand justice for those tortured, disappeared and murdered in northeastern Mexico. (Courtesy of Consuelo Morales)

Bringing advanced forensic science to find loved ones

In 2012, Morales along with several victims spoke with then-State Attorney General Adrian de la Garza to help them buy forensic equipment. Shortly after, the International Commission on Missing Persons, a Dutch group that has pioneered advanced forensic technology, donated equipment to the government through Morales to search for bodies, as they were familiar with Morales' work. De la Garza then sent a group of cadaver search experts to the Netherlands to train them to use this equipment.

For Virginia Buenrostro, who was kidnapped along with her husband and two children in 2010, this technology led to answers.

On the weekend of Nov. 13, 2010, the family was going to have a gathering, a parrillada, when Buenrostro and her husband David Ibarra were kidnapped by members of organized crime in her country house in Cadereyta, Nuevo León. They were unable to alert their children about the armed cartel members in the house waiting for them.

Morales in 2012 with then-State Attorney General Adrián de la Garza, demanding the Prosecutors General Office make it possible to bring the latest technology to find human remains from the Netherlands. (Courtesy of Consuelo Morales)

Two days after not hearing from her parents, her daughter, Jocelyn Mabel Ibarra Buenrostro, 26, went to the house, accompanied by her boyfriend José Ángel Mejía Martínez, 26, and the family driver, Juan Manuel Salas Moreno, 40. When they arrived they were also kidnapped. Two days later, the Mexican army rescued Virginia and her husband, but their daughter, her boyfriend, and the driver did not have the same fate.

After receiving a call from the criminals asking for a ransom, Virginia's son, David Joab Ibarra Buenrostro, 25, began negotiations to recover his sister, her boyfriend and the driver, but when he went to deliver the ransom a few days later he was also kidnapped by the armed group. Virginia's children and the two others were never found. (According to Human Rights Watch, the authorities' "poor response" and "their unwillingness to act on credible information of additional imminent abductions" contributed to these disappearances.)

About two years ago a body search team was taken to where her son and daughter were abducted. There, using the same forensic technology that Morales helped introduce to northeast Mexico, they found evidence their children were murdered.

"Without her I would've never overcome this grief," said Buenrostro, who never lost faith in finding her children. "We all respect her so much."

Standing before the faces of those missing, Sr. Consuelo Morales led a press conference alongside CADHAC and AMORES Nov. 26, expressing their concern for the recent increase in femicides and forced disappearances, as well as the lack of action by the authorities to activate Amber Alerts on cellphones. "We observe a lack of respect and guarantee of basic human rights in the current administration of Samuel García Sepúlveda," the governor of Nuevo Leon, she said. (Julieta Valdez)

AMORES travels to assist

Everything Morales taught to thousands of mothers and partners of victims eventually became the group known as AMORES. Buenrostro, along with other victims, travels with AMORES throughout Mexico, meeting with international human rights groups, visiting universities and sharing their testimony with students.

Women from the entire state travel to attend the meeting every Wednesday. Some ride the bus or drive for several hours to meet with Morales.

Velasco, who is also chief manager at CADHAC, called Morales "a benchmark in the defense of human rights."

"She had the wisdom and strength to support defenseless people," the attorney said. "When she started CADHAC 30 years ago, there were no organizations that defended human rights in all Nuevo León and northeast Mexico."

Sara Torres Carrizales, left, and her granddaughters, ages 17 and 18, attended CADHAC's press conference Nov. 26. They continue searching for her daughter Elia Monsiváis, who has been missing since 2010 after she was snatched from her home by a group of armed men. (Julieta Valdez)

For Alicia Garcia and Evangelina Camacho, this was their 16th Mother's Day celebration without their sons, Marco Solís and René Luna, both of whom were police officers.

They went missing while on duty in 2007 in Santa Catarina, Nuevo León. From 2007 to 2009, dozens of mothers of officers began to arrive at CADHAC seeking Morales' help to find their sons.

"How could you tell a police officer to rescue victims if they were also being taken away?" Morales said.

Still, Morales was the only person who cared enough to look for missing police offers, Camacho told GSR during a Mother's Day celebration at CADHAC, where every year Morales makes sure to have a dinner party, roses and gifts for all the mothers and to remember and pray for their missing sons and daughters.

"One of the greatest satisfactions for me," Morales said, "is when the victims tell me, thanks to you I knew that God was with me in the most difficult moments, because every time I spoke with you it made it clear to me that God was always with me."