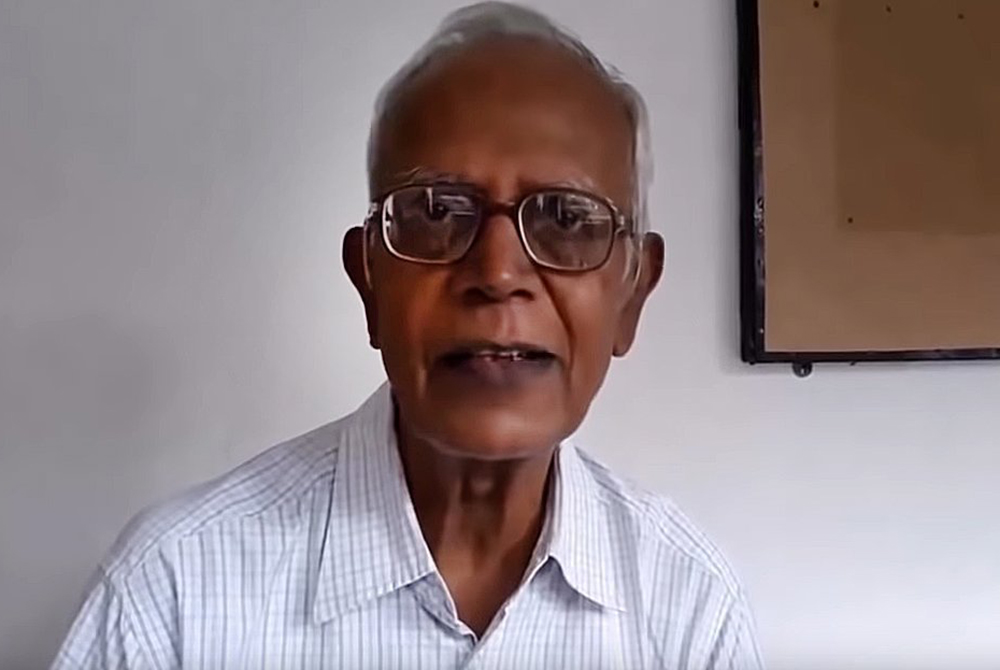

Jesuit Fr. Stan Swamy, pictured in a screenshot, who had been jailed on dubious terrorism charges since October, died July 5 at Holy Family Hospital in Mumbai, India. He had been moved to the hospital from jail in late May, under orders from a local court. (CNS screenshot/YouTube)

Jesuit Fr. Stan Swamy addresses the Right to Food Convention gathering at Ranchi, Jharkhand, in November 2016. (Sujata Jena)

On July 31, I attended an all-India campaign meeting to demand justice for Father Stan and related pressing issues of the country. Justice V. Suresh, human rights lawyer and national general secretary of the People's Union for Civil Liberty, said the government had admitted that 6,000 innocent people had been accused between 2016 and 2019 under the UAPA (Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, a counterterrorism law under which Father Stan was arrested. Only 132 were convicted.

The 84-year-old Jesuit activist, Stanislaus Arulswamy, known by his shortened name "Stan Swamy," worked for the Adivasi and Dalits — groups at the bottom of India's social and economic hierarchy. He died in judicial custody on July 5. Many called it a custodial murder.

"There is a sense of fear and lack of confidence among us. However, we must never allow injustice to be our norm," Suresh remarked at that July 31 meeting, adding that with the death of Father Stan, the church's demands for UAPA's repeal is over. He pleaded for us not to be silent spectators to the injustice.

"My work involved defending the constitutional rights of the Adivasis and Dalits of Jharkhand and other eastern Indian states. This, I believe, has become a bone of contention between the state and judicial system," Father Stan explained in a video message before he was arrested. "So they wanted to put me out of the way."

Father Stan was arrested because he challenged the policies of the state regarding the constitutional rights of the tribal and Dalit people. The Indian government punished him for his tireless efforts in helping the Adivasis and the lower caste majorities.

The government aimed at silencing him and warning others against similar activities. They succeeded — hunting down a fiery citizen and a prophet of our time.

I first met Father Stan in 2016 at a Right to Food Convention in Ranchi-Jharkhand, the northeastern Indian state. I had traveled with about 300 Dalits and a tribal self-help group of women on a crowded overnight train journey to take part in that convention while I was working in a Jesuit-run social action forum in Kolkata.

Over 6,000 tribal, Dalits, women and men had joined the national protest. Jesuit fathers Swamy and Irudaya Jothi were among top national food activist leaders at the convention.

Then 80 years old, Father Stan censured the vast crowd and criticized the government for not implementing constitutional protections for the Adivasi community. I imagined Jesus feeding, healing, teaching and siding with the most vulnerable. "Smart religious," I said to myself. They live out prophetic calls.

Advertisement

There has been an outpouring of grief over Father Stan since his death. He wasn't hiding behind four walls. He was in the field, fighting for the rights of the people. Everyone knew Father Stan was right, and that we should imitate him. He may be the most well-known Christian in India after Mother Teresa, possibly receiving more media coverage than Mother Teresa.

It did not seem to me that the church was overtly supportive of Father Stan. Perhaps he wasn't always appreciated because he challenged the institutional church to wake from its slumber and complacency.

Father Stan was arrested Oct. 8, 2020, and while he was in prison for nine months, I did not notice many public comments coming out from the Indian church, religious collectives or India's best known educational institutions before or after his death. But the Vatican made note of it on Oct. 12, and a group of Jesuits took up a campaign — #Stand with Stan.

To my knowledge, even Father Stan's own province didn't openly support him when he was in prison. The local church authorities and religious seemed afraid to come out in the streets to demand justice for Father Stan.

Perhaps he wasn't always appreciated because he challenged the institutional church to wake from its slumber and complacency.

But when the media and civil society came out with a series of online and offline protests, the church apparently woke up. Cardinal Oswald Gracias, archbishop of Bombay, followed the call of Jesuit Fr. Stanislaus D'Souza, president of the Jesuit Conference of South Asia, and urged Indian dioceses to observe July 28 as National Justice Day, to demand justice for Father Stan. The Jesuit Conference expressed solidarity with him, as did Jesuits of the U.S. and Canada

Conveniently, we seem to interpret the prophetic call to be loyal to the established system and established way of life. I think there is a clear division between traditional "institutionalized" religious and the "grassroots" religious.

Religious and priests who commit to stand for the rights of the poor and marginalized often do not get support. Their work of justice is seen as anti-religious, anti-Christ. Religious who do not tolerate traditional, institutionalized religious life suffer for a lifetime. Some who can't take it anymore take the drastic step of quitting their way of life.

We willfully ignore the religious' desire for social justice — rooted in Jesus of Nazareth, who took the side of the poor (Luke 4:18-19) to accompany the poor, prisoners, give sight to the blind and liberation to the exploited. Christians' demand for social justice has a biblical root: Yahweh sent Moses to deliver the Israelites from slavery. The prophets spoke vividly of injustice.

"Be prudent" is the maxim of religious leaders for their members fighting injustice. At times, it simply means to withdraw from the struggles with the vulnerable and pray for them in the comfort of the well-decorated chapel — as silent spectators to injustice.

We read that thousands of our people languish in jail unjustly, millions go hungry without food, hundreds are lynched, abused, assaulted daily. Can we continue to cultivate a callous heart? Can this be "prudence?"

Unfortunately, it seems the church is a silent spectator to injustice, going against Catholic social teaching, against the teaching of Christ. The real tribute to Father Stan should not necessarily be to put him on a pedestal and honor him as a saint, as an extraordinary person who we cannot follow — but to share in his vision of being part of the struggles of the poor and the outcast, the fundamental mission of the church.

I believe he would like to see himself hailed as an ordinary man who stood for his convictions all his life. This would inspire India's 1,30,610 professed religious to live in solidarity with the most deprived, defending their rights and dignity, and making a preferential option for the poor possible. God's kingdom of love, justice and peace should be experienced by all.