A group of women religious from China may turn out to be innovators of a very particular kind — and that has everything to do with China's changing demographics.

Six Chinese sisters from five different congregations recently completed a 120-hour Geriatric Spiritual Care certificate program through the Avila Institute of Gerontology, the educational arm of the Carmelite Sisters of the Aged and Infirm. The Avila Institute compressed a four-month program into four weeks, said Fr. Timothy Kilkelly, the coordinator of the Maryknoll China Education Project. "People can't come for four months, so compressing the program was a great service to us."

The sisters were in the United States in May and June under the auspices of the Maryknoll China Education Project, which since 1991 has brought priests and women religious to the United States for graduate academic studies at Catholic institutions.

The six sisters are the first brought by the project to the U.S. to study geriatric spiritual care. The Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers are funding the program, which is also the first to focus on short-term training and not graduate-level degree courses.

"Each of their congregations is already engaged in providing assisted living and nursing home care, as well as other programs of ministry to the elderly in China," said Sr. Janet Carroll, Maryknoll China Programs liaison. The goal, Carroll said, "is having this team of sisters extend their training to other sisters and lay partners upon their return to their local dioceses in China."

The need for such training becomes clear given that China is in the midst of huge social changes affecting the family. Traditionally, adult children took care of elderly parents and relatives. That was the norm for centuries and was a particular dynamic in rural areas.

But in the midst of rapid urbanization, young people are leaving their parents and other relatives for jobs in cities. That means families are facing some of the dilemmas long experienced by Americans — for example, whether elderly people should be placed in nursing homes once they have difficulty living on their own.

"The aging of society is one of the key challenges China now faces, in addition to internal migration and urbanization," said Kilkelly.

As a result, nursing homes — once rare — are becoming more common in China, as is the need for increased attention to institutional care for the elderly. Overall numbers in the country are sketchy, but Kilkelly said 50 such homes are run by Catholic religious congregations and the other 50 by Catholic dioceses and some by individual Chinese Catholics concerned about the elderly. About 200 other nursing facilities are run by Protestant churches and groups.

Those numbers are still relatively modest when in light of China's huge population (1.37 billion) and geographic size (3.7 million square miles, almost 6 million square kilometers). Yet more are expected to be built in coming years as the number of elderly residing in nursing homes increases, which is where sisters like Sr. Pauline Yu, of the Our Lady of All Souls congregation, and Sr. Fabian Han, of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters, come in.

With their recently acquired training — a four week program held May 19 through June 16 — Yu, Han and the team of other sisters will start training others in the area of geriatrics and spirituality within their local dioceses in China.

As four of the six visiting sisters noted in a recent joint interview with Global Sisters Report at the Maryknoll Center, China is not yet prepared for the changes underway. "We're not ready for this, the aging of society," Han said about the wider Chinese context. This is particularly the case, she said, in rural areas "where the elderly are being left behind."

"They can feel hopeless," she said.

One way of looking at the challenges facing China involve what is called the "4:2:1 problem," which stems from the country's long-standing "one-child" policy. Writing in the China Business Review about senior care, journalist Christina Nelson noted that there "are now four grandparents and two parents for every one working Chinese." While many Chinese still like the idea of the "Confucian ideal of filial piety towards their elders, the combination of relocation, and the number of family members in need of care, make doing so no longer feasible," Nelson wrote in 2012.

Howard W. French, writing recently in the Atlantic magazine, noted that from 2000 to 2050, "the median age in China will go from under 30 to about 46, making China one of the older societies in the world." He added that the number of Chinese older than 65 is expected to rise from roughly 100 million in 2005 to more than 329 million in 2050.

This will put increased pressure on institutions like the Catholic Church to provide care for seniors — an enormous task that could beeven more challenging given the relationship between the Chinese government and the church right now.

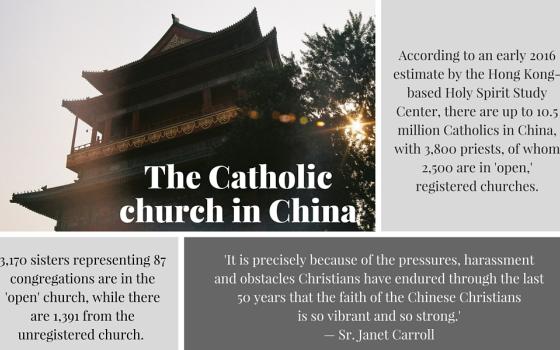

There are about 60 million Christians in China — about 10 million of them Catholic — and people attend churches both registered and unregistered with authorities. Tensions between the church and the Chinese government exist over a number of issues, with President Xi Jinping recently expressing the need for religious institutions to "Sinicize," or "become Chinese." He has argued that religion has been used to infiltrate society from the outside, The New York Times reported. Parallel to this, churches in China report that as many as 1,700 crosses have been removed from churches by authorities in recent years.

Carroll told GSR she believes the more important narrative in China in recent years is "the story of what the churches are doing despite persecution," and that includes the needed ministry to the elderly in care facilities — a ministry that will only expand in coming years. "That's the real story of the church right now," she said.

She also cautions against making too much distinction between open-registered and unofficial-unregistered churches. "These are in reference to local Catholic communities of Catholics which take different approaches to complying with civic law," she said. "There are no doctrinal or theological distinctions, which is why we speak of only one Catholic church in China."

For their part, the Chinese sisters, just coming off of their time with Avila, said they are enormously indebted to the program, which involved an initial orientation at the Avila Institute of Gerontology in Germantown, New York, followed by the program's main component — roughly a month at the affiliated St. Patrick's Manor in Framingham, Massachusetts, near Boston.

Sr. M. Peter Lillian Di Maria, director of the Avila Institute of Gerontology, told GSR in an interview that the sisters from China "were the greatest students, with a great willingness to learn all they possibly could."

In their clinical work in Massachusetts, she said, the residents "loved the sisters" because of the one-on-one attention they provided the patients. "The residents loved having them visit," Di Maria said. Both residents and support staff hated to see them leave. "The sisters were very much missed when they left. They had become part of the larger community very quickly. They fit right in."

The sisters' stay was the first time Avila had hosted a group of students from outside the United States for the geriatric care program — making the China sisters pioneers for Avila, as well as for Maryknoll. Di Maria said Avila is "very open" to repeating the experience for a group from any country. "People are people," she said. "And people want to help each other, to serve one another no matter what the nationality or culture."

Spiritual care — which Kilkelly said is broadly "that dimension of care that focuses on the spiritual and religious needs of the person brought on my illness, injury, or aging," is particularly necessary for what the Avila Institute called "frail elders."

"The issues that focus on life and death, meaning and purpose, loneliness and loss are often magnified when the individuals [are] placed in a long-term care facility," states the Avila certificate program syllabus.

Among the topics covered in the program were dynamics of spiritual care, active listening, theology of suffering and moral ethics. In addition to course work, 55 hours of clinical work over seven days were also required for the certificate.

Sr. Maria Wang, of the Our Lady of All Souls congregation, said she was particularly enriched by the program's emphasis on how best to help those with dementia — stressing the need for patience, the need to listen attentively to patients' life stories and seeing, as best as possible, "the whole person."

"It is the difference between holistic care and custodial care," she said, noting that the holistic emphasis is an important part of the need for a spiritual approach to elder care.

The mere act of presence with patients is vital, said Sr. Theresa Liu, of the Daughters of Charity congregation. "Just being with them is important," she said. "Be with them, listen to them."

Facing depression through behavior management is also important, said Han, and is a needed corrective to nursing care in China which often focuses only on the physical aspects of care. "We really haven't paid enough attention to psychological concerns and spiritual needs, and this is what I bring back home to my work. It is really, really important."

The time at the nursing center near Boston impressed the sisters in part because of the way small things add up. This can include making sure that patients dress carefully and pay attention to looking good. "They were elegant, and that's important," Yu said of the patients she met.

Underlying the sisters' belief that "people in the last period of their lives deserve dignity and respect," said Wang, is the sisters' own faith commitment to their work and "to be a real human presence for the elderly."

A key part of what the sisters will now do is not only training other sisters but lay staff and volunteers. There is not a long tradition of volunteers working in nursing homes, but that needs to change, Han said.

"The sisters," said Carroll, "can't do everything alone."

With this first program in non-graduate degree studies completed, Kilkelly is looking for other training that could be adapted for the model. "The next short-term training program will likely be in another area of specialized training that the local church is requesting," he said. "It could be in leadership training, or parish management. It really depends on what the pressing needs are that could be addressed by short-term study."

The six sisters are also expected to help the Maryknoll China Education Program "identify future certificate students who will come in the future to do the Avila Institute Program," Kilkelly said, noting that the Avila Institute requires six people before proceeding with providing the program, so the next short-term training model will probably not be in geriatric care.

"The challenge for us is finding people who can do the English,'' he said. "We think that in another two to three years, we should be able to identify another cohort who will be capable of the challenge."

The challenge now for the six sisters who have returned to China is imparting what they learned in the United States to their local contexts. Wang calls it a "wider view" in order to do more.

Han agrees. "We've only tended to pay attention to the physical needs of patients," she said. "We really haven't paid attention to psychological and spiritual needs. Now we will. That is what I am bringing back home to China."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR's international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]

Sr. Janet Carroll on religion in China: Catholic faith in China is tradtional and deep