Imagine a young nun in the 1960s. The old boys network, clerics and bishops in princely vestments, call the shots. Women are expected to know their place. Now tell that sister that in a few decades she will be the one praised by a president, huddling with financial titans in Davos, briefing cardinals in Rome, and widely lauded as one of the most influential leaders in health care.

Five decades later, Sr. Carol Keehan, president and CEO of the Catholic Health Association of the United States, chuckles when asked if she ever expected to travel in such rarefied circles.

"I always thought I would grow old as the sister nurse in the emergency room," Keehan said in her office in downtown Washington, D.C. "I had no aspirations for this. I have always loved the emergency room and always wanted to be there."

Keehan recently announced she will retire at the end of June 2019, bringing to a close nearly 14 years of executive leadership at the Catholic Health Association (CHA).

At a time when the Catholic hierarchy is barely clinging to any remaining moral credibility given its systematic failure to address the clergy sexual abuse crisis, one of the church's brightest lights is a nun who keeps a simple room with a bed and a desk at a Maryland convent. If the sister with an unassuming personality who often grills up dinner for her fellow sisters on the weekend strikes a low-key profile, there is nothing understated about her legacy.

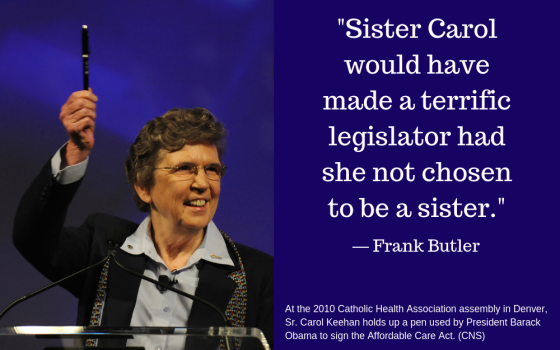

Keehan played such a major role in helping to pass the historic Affordable Care Act in 2010, she received a pen from the signing ceremony. Time magazine named her one of the "100 Most Influential People in the World" that same year.

Pope Benedict XVI awarded her the prestigious Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice (Cross for the Church and Pontiff) in 2006. When he visited the United States in 2008, the Vatican asked her to lead the pope's medical team. In the motorcade, she rode in a car behind the pope, surrounded by burly Secret Service agents.

At a gala dinner event in New York City in October 2018, Commonweal magazine honored Keehan with its Catholic in the Public Square award. Among those praising her that night were Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey, Barack Obama and Joe Biden, all of whom sent glowing video tributes.

The tributes come from the trenches as much as from the luminaries.

Long before Bill Strudwick became emergency room medical director at Providence Hospital in the nation's capital, he was just a kid who knew Keehan as the woman who ran the hospital where his dad worked.

"Sister Carol always had a great concern for everyone who worked here, from the doctors to custodial staff," Strudwick recalled. "She knew the families, your stories, your struggles. Whether it was a patient, a politician or a CEO, she always treated them with joy and respect. Doctors who could have left and made more money elsewhere didn't want to leave. We had a mission here, and she really created that environment."

Michael Rodgers, senior vice president for advocacy and public policy at the Catholic Health Association, has worked with Keehan for more than a decade. "She has an extraordinary commitment to care for people who are vulnerable," he said. "She's clearly a skillful administrator and executive, but the people we serve are her focus."

Commitment to the peripheries

Keehan's commitment to those on the peripheries — and her reputation as a pragmatic leader who can get things done — is global. When a devastating earthquake struck Haiti in 2010, killing more than 230,000 people and leaving more than 2 million people homeless, she quickly pulled together a fundraising drive with Catholic Relief Services to rebuild St. Francis de Sales Hospital in Port-au-Prince. In only a few months, the Catholic Health Association and partners raised $10 million for the project.

A Catholic Health Association video for St. Francis de Sales Hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti

"We had never built a hospital before and her assistance was critical," said Sean Callahan, president and CEO of Catholic Relief Services. Keehan served two terms on the CRS board. "Sister Carol helped health care networks overseas not only with technical assistance, but she opened the door to provide mentoring support. She is a wise and selfless leader."

Keehan entered the Daughters of Charity at 19 years old, staying only six days. But Keehan, who met sisters from the religious order when she was in nursing school in Norfolk, Virginia, came back two years later, in 1964.

Born in Providence Hospital, where later as a young nurse she watched from the rooftop as Washington burned after Martin Luther King's assassination in 1968, Keehan became president of the hospital in 1989, and stayed in that position for 15 years.

The hospital that holds a special place in her heart is now only operating as an emergency room and a 10-bed inpatient facility. It is slated to close fully by April 30, a controversial decision made by Ascension, the world's largest Catholic health system, which took over operations of the hospital from the Daughters of Charity. Staff and community members in northeast Washington have protested that the closing is a shortsighted financial decision that will leave a low-income area with far less access to medical care. Keehan is clearly pained by the decision, but does not comment publicly to avoid the perception of interference.

As to the timing of her upcoming retirement, Keehan says the Catholic Health Association, which includes more than 600 hospitals and 1,600 long-term care facilities in every state, is anchored by a strong executive team. "I'm healthy but when you're 75, you have to look at the stats on health. The most important goal for me is a smooth transition. I want the Catholic Health Association tomorrow to be even better under someone else's leadership than it is today under mine."

Those are big shoes to fill.

"I would be less than honest if I didn't express some concern about the future of Catholic health care without Sister Carol's leadership," said Frank Butler, who served for three decades as president of FADICA, a network that connects foundations and donors to support Catholic causes.

Butler, who calls Keehan "one of the truly extraordinary Catholic leaders of our time," first collaborated with her in the 1980s, when she helped launch a campaign to bring greater awareness to the struggles of priests, women religious and others who served the church but were left with few resources for their care in retirement.

Butler marvels at Keehan's ability to be at once a policy wonk, consensus builder and moral leader. "Sister Carol would have made a terrific legislator had she not chosen to be a sister," he said. "Her extraordinary ability to master the details of health policy from a national perspective down to the level of bedside care is phenomenal, but so, too, is her understanding of sharply opposing points of view. She is able to stay anchored to her principles grounded in the Gospel and Catholic social teaching while ably working for what's possible and workable, given the competing points of view at work in making public policy."

Crucial to health care reform

Those nimble skills were tested during the often-bruising fight to achieve health care reform in the U.S. The Affordable Care Act, which narrowly passed Congress in 2010, not only became a proxy war for a host of divisive political issues, but also split the Catholic Church in the United States.

While universal health care as a human right has long been a pillar of Catholic teaching and a goal of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, conference leadership concluded that the legislation would fund abortion and did not support the final bill. The Catholic Health Association disagreed with that assessment. Keehan became the face of Catholic lobbying efforts to pass the historic bill.

"We would not have gotten the Affordable Care Act done had it not been for her," President Obama said about Keehan at a CHA assembly in 2015.

In the heat of that battle, the backlash from conservative Catholic media and bishops was fierce and personal.

"Your enthusiastic support of the legislation, in contradiction to the position of the bishops of the United States, provided an excuse for members of Congress, misled the public and caused serious scandal for many members of the Church," Bishop Thomas Tobin of Providence, Rhode Island, wrote in a letter to Keehan. The bishop asked the Catholic Health Association to remove his diocese's St. Joseph Health Services of Rhode Island from CHA membership rolls. "Even the association with CHA is now embarrassing," the bishop added with a jab.

Until the end, Keehan remained hopeful the bishops' conference would support the legislation. She had a good relationship with the late Cardinal Francis George of Chicago, then conference president. "We talked many times, and Cardinal George wanted to be on record with me supporting the legislation," Keehan said. "CHA was clear from the beginning that we could not support the bill if there was federal funding of abortion."

In the critical final days before passage, Keehan asked the cardinal if she could visit him. The two spent several hours in the cardinal's residence over lunch. Keehan brought him a potential draft letter the two could sign, expressing support for the legislation. "The cardinal read it very carefully and said, 'I like this letter a lot. I might change a few words, but I like it.' He wanted to sign it and told me I would hear from him in a few days."

Keehan never heard back. Her perception is that a cadre of staff at the bishops' conference, and the cardinal's advisers, convinced George the law would fund abortion.

Painful personal attacks

While Keehan cites passage of the Affordable Care Act as her proudest accomplishment, she also acknowledges that the narrative of division in the church troubled her, and the personal attacks stung.

"It was extraordinarily painful," she said. "I've always worked in the church and for its ministry. It got very ugly and aggressive." Keehan was removed from Vatican committees, lost speaking engagements and was picketed more times than she can recall.

Las Vegas Bishop George Thomas, who became a CHA board member three years after the health care law passed, believes time and effort have helped heal those wounds.

"I've seen a lot of bridges built between the Catholic Health Association and the bishops' conference since then," Thomas said. He credits Keehan for "investing heavily in keeping the conduits of dialogue open" with the hierarchy.

"She will be a hard act to follow," Thomas admits, citing her sophisticated command of policy and ability to connect with everyone from senators to administrative staff. "But there is a native humility to Sister Carol, including a delightful sense of humor. As she herself has said, this is an opportunity for new leadership and the executive team to continue to strengthen CHA."

Former Rep. Bart Stupak, an anti-abortion Michigan Democrat who communicated closely with the bishops' conference during the health care fight, points to her steadfastness and integrity. "She was a strong voice not only advocating for health care reform but also protecting the Catholic viewpoint on abortion," said Stupak. "Even though it wasn't a perfect bill, we both thought it reflected our Catholic values. Sister Carol kept her eyes on the prize."

Joshua DuBois, an adviser to Obama who led the Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, was even more effusive. "Her legacy is pretty extraordinary," DuBois said. "I think she is one of the most important religious figures in the last 50 years."

The Obama White House and Keehan didn't always agree. When the Department of Health and Human Services issued guidelines for the health care law that required most insurance companies to cover contraception as part of preventative medical care, initially only churches and houses of worship were exempt. The original guidelines did not exempt Catholic hospitals or charities integral to Catholic identity and mission.

Some commentators viewed the "contraception mandate" as a slap in the face to Catholic social justice leaders who had supported the Affordable Care Act even in the face of bristling criticism. Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, a liberal Catholic, wrote that the Obama administration had left Keehan "hanging out to dry."

Keehan called Obama and worked with the administration to broaden exemptions for the contraception coverage requirements. "Sister Carol was always candid and frank," DuBois recalls. "Even when she disagreed with us she did it with great love. She has such a winsome way of navigating faith in public life. Even when there was disagreement, she could rally people to her cause."

Far from the White House and political fights, fellow Daughter of Charity Mary Bader observed Keehan through a different lens. The CEO of St. Ann's Center for Children, Youth and Families, Bader still remembers the first time she encountered Keehan, in 1990. "I was working with a young girl whose mom had a very serious drug problem, and we needed help. I called Sister Carol cold. I didn't know her. She was at Providence Hospital. She said, 'Bring her in tomorrow and we will take care of her.' And she did. That's when I realized this is one remarkable person."

In the 1960s, Keehan worked briefly at St. Ann's, a center across the District border in Hyattsville, Maryland, that was founded in 1860 by the Daughters of Charity and officially incorporated by President Abraham Lincoln three years later. Keehan watched over the newborn infants. Not long ago, a woman showed up at St. Ann's with a burning memory and a question.

"She told the story of having a child here, and remembered this one young sister who was so comforting and caring," Bader recalled. "She wanted to know the name of that special person from all those years ago. It was Sister Carol."

[John Gehring is Catholic program director at Faith in Public Life, and author of The Francis Effect: A Radical Pope's Challenge to the American Catholic Church.]