When Pacifique Uwimbabazi, 23, has a problem, like many millennials around the world, the first thing she does is reach for the phone to text someone she can trust and ask for advice.

The person receiving the text message is Sr. Athanasie Kayigamkia, an Abizeramariya Sister who raised Uwimbabazi from birth, after her parents were killed in the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Uwimbabazi's mother was killed just a few days after giving birth, so Uwimbabazi was raised as a newborn at the Abizeramariya home in Huye (formerly Butare; many place names changed after the genocide).

"Our orphanages only came after the genocide," said Kayigamkia, now a nurse who oversees the Matyazo Health Center, a Catholic health clinic in Huye. "We took in children because they had nowhere else to go. Our main objective was the elderly, but we saw so many kids in the streets who were coming to us for help, so we decided to open orphanages."

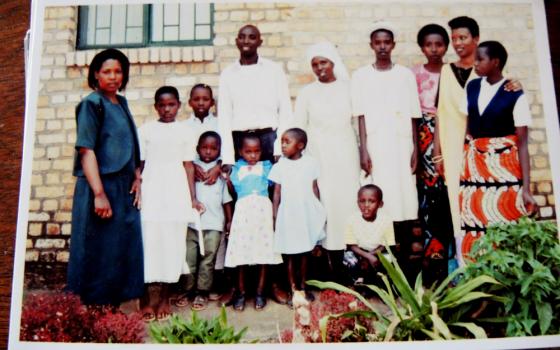

Almost overnight, the six Abizeramariya homes for the elderly were transformed into boisterous orphanages with more than 40 children each. At each home, the children lived together with about a half dozen older people, as the sisters wanted to maintain their commitment to the elderly.

"We helped the children not only for the children themselves, but also for the country," said Sr. Marie Agnes Nysera, another Abizeramariya sister living at the orphanage and elderly home in Huye. "To help these kids was living for God's sake."

Abizeramariya means "Those who trust in Mary" in the local language of Kinyarwanda. The congregation is the second-oldest one in Rwanda and was founded in 1956. Today, they have 160 sisters in 13 communities in Rwanda, Kenya and Uganda.

During the genocide, many of their convents were refuges for Tutsis fleeing the killing, and many people sought out the sisters in order to hide family members and children, according to testimony from the International Criminal Tribunal Courts.

"I was basically born in the home and lived there all my life until I was in primary four [high school]," said Uwimbabazi. "I grew up there. They took me as their own kid."

Uwimbabazi has two older sisters, an aunt and a handful of cousins who survived the genocide. She stayed in touch with her surviving family and went to visit them on holidays. But with the country in tatters after the genocide, caring for extra children was sometimes impossible, so Uwimbabazi stayed with the sisters.

Kayigamkia gave Uwimbabazi her first name, Pacifique. "We wanted you to have peace and blessing from God," she said.

For high school, Uwimbabazi followed in the footsteps of a cousin and gained admittance to the Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village, a boarding school for vulnerable teenagers that is celebrated for its emphasis on creativity and entrepreneurship.

At Agahozo-Shalom, Uwimbabazi joined the leadership club and TV club, where she created weekly news bulletins about international and local news that were screened during Friday lunches.

Now she hopes to attend university, either in Rwanda or abroad. She is waiting to hear about a scholarship to study economics at McGill University in Canada, or international business at the African Leadership University in Kigali, or the Rwanda National University.

"I'm going to be a businesswoman, or maybe a clothing designer, because Rwanda has a lot of secondhand clothes but I think in 10 years there will be more of a market for new clothes," said Uwimbabazi.

She returned to the orphanage where she grew up to share good news with the sisters who raised her: She had recently scored 67 out of 73 on her National Exams (similar to the SATs).

Kayigamkia said the sisters prayed that Uwimbabazi might feel called to be a nun, which makes Uwimbabazi laugh. Although she was raised Catholic, in the past year she decided to become Anglican. "I explained to the sisters, it's my choice, now that I'm older I can choose, and they said OK," said Uwimbabazi.

"To see these young ones graduating is amazing," said Kayigamkia. "These graduates will have a good future." Two other children who grew up with Uwimbabazi at the orphanage are now at the Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village and will graduate in December.

"We must help the young ones, give them care and love, for they are the future of Rwanda," Kayigamkia added. "They are the doctors and the teachers of tomorrow."

Uwimbabazi is among the last genocide survivors to graduate from high school and leave the sisters. Now, almost 60 percent of Rwanda's population is 24 or younger, meaning they were infants during the genocide or born afterward.

In the past decade, the country has embraced the UNICEF and international approach to orphans, which emphasizes placing them with relatives within their communities rather than at separate orphanage facilities.

"It's good to help the young ones, but it's better to grow up with their own families rather than the nuns," said Kayigamkia, though she notes that approach was impossible in the aftermath of the genocide, when poverty and hunger were widespread.

She said most of the children who grew up at their facilities have left, either to study or to start their own families. "One of the challenges with the orphans is that we are not able to finance their [continued] education," said Kayigamkia. A few of the orphans, like Uwimbabazi, were able to obtain scholarships and continue their education, sometimes even through university.

A few children, now young adults, are struggling and still live with the sisters. Some have mental or emotional issues and are unable to live on their own. But for the most part, the Abizeramariya Sisters have returned to their original purpose of serving the elderly. They serve about 240 elderly at their six homes, providing them with food, accommodations, clothes and spiritual support, said Kayigamkia.

Today, Uwimbabazi lives down the street from the orphanage where she grew up, staying with a cousin while she waits to hear where she will study next year. She's busy watching her cousin's three children and doesn't visit her old home all the time, she said.

But when she does, the sisters always remember to put out a plate of roasted ground nuts — peanuts — on the table as they sit in the common room and catch up, hearing about Uwimbabazi's plans for the future. "They remember that I like the ground nuts," said Uwimbabazi.

"It's like coming home. It feels good to come home. They're like my mothers," she said. "Being an orphan is not a choice, but if you have purpose in your life, you don't have to feel alone."

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]