In the Ugandan slum of Kamwookya, there's a small school called the Sr. Miriam Duggan Primary School. It caters to children whose families were displaced from Acholiland in the north of the country, forcing them to seek refuge in the capital, Kampala. Many of these families struggle with poverty and HIV, and some of the students are orphans.

The school is named after one of the country's leading pioneers in home care for those with HIV/AIDS. Duggan also played a significant role in Uganda's successful ABC campaign, which emphasized fidelity and abstinence. After the campaign, infection rates dropped among those ages 15 to 49 from 18.5 percent in 1992 to 6.4 percent in 2005.

Duggan, who is originally from Limerick City in southwest Ireland, joined the Franciscan Missionary Sisters for Africa in 1956 and trained as a medical doctor at University College Cork, graduating in 1964.

In Dublin in December, the 79-year-old looked tanned and relaxed. She flew in from Kenya, where she now works with the Franciscan Missionary Sisters for Africa's Hands of Care and Hope program in the slums of Nairobi, to receive a Presidential Distinguished Service Award for the Irish Abroad in recognition of her "tireless medico-humanitarian work on the African continent across the fields of midwifery and the care of those afflicted by HIV/AIDS."

She also delivered the 2015 Irish Aid Annual Professor Michael Kelly Lecture on HIV/AIDS at the Royal College of Surgeons on Dec. 10 in the Irish capital. Her theme was "Keeping HIV on the Agenda: Women's Unequal Equality."

Promoting responsible behavior is not just about HIV/AIDS, she told Global Sisters Report. In one of the schools where she works in the parish of Kariobangi, a slum in Nairobi, Kenya, 64 percent of the students are single mothers with no support from the state, she said.

The teenagers "are eking out an existence. What is that doing to future generations?" she said. "Education and knowledge are so important. The girl needs to know she has a right to say no."

Empowering teenage girls to say no to early sexualization and teen pregnancy is one aspect of the Hands of Care and Hope project, which operates in Kariobangi and two other Nairobi slums, Huruma and Madoya. The project also offers education and training to young men and women to help them out of poverty.

"We tell them if you are born into a poor area, you don't have to stay there," Duggan said. "You can get out of it. But it is hard work, and you've got to be motivated. We use all sorts of motivations, such as Obama's slogan, 'Yes we can.' But without education and employment, you will never get people out of poverty."

Hands of Care and Hope runs three schools and a youth center. "The schools are for out-of-school children," Duggan said. "Many of them have been rescued off the dump heaps. We provide breakfast and lunch to them."

The program also caters to those living in difficult circumstances, such as those with HIV/AIDS. Other participants in the project receive skilled training appropriate to their talents in areas such as driving, hairdressing and secretarial work.

In her address to the Royal College of Surgeons, Duggan noted that in Kenya, surveys show that HIV prevalence among women and men between the ages of 15 and 49 years ranged from 6.7 percent in 2003 to 5.6 percent in 2012. Although the rates are on a downward trend, women are disproportionately more affected than men. There is a very high prevalence rate among sex workers (29.3 percent) and among injectable drug users (18.3 percent).

"Poverty is still playing a big role in the spread of HIV," Duggan said. "Mother-to-child transmission is another important area which needs more attention. While many strides have been made, there is still a lot to be done."

According to Pius Okong, chairperson of the Ugandan Health Service Commission and a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Uganda Martyrs University, Duggan is something of a pioneer. The Irish nun mentored him when he started as an intern in 1980 at Nsambya Hospital in Kampala.

In a 2014 letter supporting Duggan's nomination for the Presidential Distinguished Service Award, Okong wrote, "Between 1988 and 1991, Sr. Miriam's foresightedness enabled Nsambya Hospital antenatal clinic to be one of the few HIV sentinel surveillance suites. This was the only source of data about HIV in the population."

"She also pioneered the setting up of Home Care Services for HIV, a humanistic and holistic approach to HIV/AIDS sufferers in the comforts of their homes involving relatives and friends rather than abandoning them in hospital with terminal illness with no cure."

This model of care was extended to 21 African countries and led to a Ugandan presidential award as well as honors from Harvard University and Holy Cross College in the United States.

Duggan got her start in the conservative institutional church in 1950s Ireland. The Irish church at the time frowned on women religious studying medicine or midwifery. But that didn't deter her: Off came the religious habit and on went the "civilian" clothes, and Duggan plowed ahead with her studies.

After an internship in the Royal Hospital in Wolverhampton in the United Kingdom, she went on to do postgraduate studies in obstetrics and gynecology in Birmingham, obtaining her MRCOG (Membership of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) in January 1969. That same year, she was dispatched on mission to Uganda and became a consultant obstetrician and gynecologist at Nsambya Hospital.

"We had a big training school in Uganda which wanted to upgrade its midwifery training and they needed a resident gynecologist for that," she said. The hospital was a referral hospital for a number of outstations and clinics, so much of Duggan's work involved complicated obstetrics cases as well as facilitating the training of midwives and, later, doctors.

In 1991, at the height of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, Duggan attended a meeting on AIDS prevention organized by the development agency CAFOD in Senegal. Up to 50 people from six African countries and a number of different Christian churches agreed at the meeting that change in behavior was the most essential strategy in overcoming the pandemic.

Duggan spearheaded the setting up of Youth Alive clubs, positive peer support groups.

"Many of the youth admitted the reason they indulged in sex, drank alcohol or took drugs was because they wanted to belong to the group," she told Global Sisters Report. "Facilitators also worked on character formation and helped young married couples in their journey to remain faithful to each other."

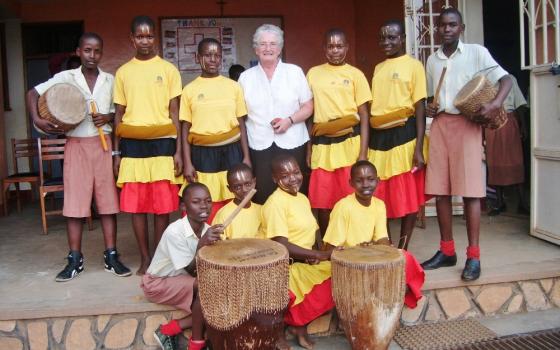

Youth Alive clubs are now active in 240 schools, parishes, colleges and universities in Uganda and in several other African countries.

Duggan said she is concerned by the cavalier way condoms have been promoted as a panacea for the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In her address to the Royal College of Surgeons, she said:

As a doctor and gynecologist, I never cease to be amazed by the way condoms are promoted to the youth as the answer to AIDS when we know the failure rates in preventing pregnancy, know the breakage rates, know they often are not affordable, and when people are under the influence of drugs and alcohol are often not used. In my estimation, the free and indiscriminate distribution of condoms in schools and the wide advertising of them in a glorified way has encouraged more young people to become sexually active because they believe the device will make them safe.

Faith has kept Duggan in religious life and kept her dedicated to her medical ministry in Africa, though it was at times "hard in every way and circumstance."

"I don't think any money would have made me do it," she said. "It was commitment to the church, faith and Gospel values that kept me doing what I did. Many times, you had to do things that you weren't trained to do and you prayed your way through them — and it was amazing the way things worked out."

[Sarah Mac Donald is a journalist based in Dublin, Ireland.]